Powering a whole country is a big task. The equipment that make up power stations and electricity systems are measured in tonnes and miles, and pump gigawatts (GW) of electricity around the country. With the world’s electricity increasingly coming from renewables, this big thinking is key to powering long-term change.

From taller wind turbines to bigger batteries, these are the massive structures breaking energy records.

Germany’s giant wind turbine and the plan to beat it

As wind power becomes ever more prevalent, one of the key questions that needs answering is how to get more out of it. One way is to build taller turbines and longer blades. Putting turbines higher into the air sets them into stronger wind flows, while longer blades increase their generating capacity.

The world’s tallest wind turbines are currently in Gaildorf, Germany and stand at 178 metres with the blades tips reaching 246.5 metres. Built by Max Bögl Wind AG, the onshore turbines house a 3.4 megawatt (MW) generator that can produce around 10.5 gigawatt hours (GWh) per year.

However, turbines continue to grow and GE has announced plans for the Haliade-X turbine, which will ship in 2021. At 259 metres in total the offshore turbine is almost double the height of the London Eye and will spin 106 metre blades, generating 67 GWh per year.

China’s ‘Great Wall of Solar’

China has pumped substantial investment into solar power, including the world’s biggest solar plant in electricity generation and sheer size. Dubbed the ‘Great Wall of Solar’, the Tengger Desert Solar Park has a capacity of more than 1.5 GW and covers 43 km2 of desert.

The next largest, by comparison, is India’s Kurnool Ultra Mega Solar Park, which covers just 24 km2 and generates 1 GW. However, rampant investment by the country means there are several projects in the pipeline that will break the 2 GW mark and will set new records for solar power plants.

Morocco takes solar to new heights

Concentrated solar power (CSP) takes the technology skywards by using thousands of mirrors, known as heliostats, and focusing the sun’s rays towards a central tower. This heats up molten salt within the tower, which is then combined with water to create steam and power a turbine – like in a thermal power plant.

Morocco’s Noor Ouarzazate facility (pictured in the main photo of this article) is home to the world’s tallest CSP towers. At 250 metres tall, 7,400 heliostats beam the sunlight at each tower, which have a capacity of 150 MW and can store molten salt for 7.5 hours. Its record will soon be matched by Israel’s 121 MW Ashalim Solar Thermal Power Station when it begins operating this year.

However, never one to be outdone when it comes to tall structures, Dubai plans to build a 260 metre CSP tower in 2020 as part of the Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum Solar Park, which at 700 MW will be the world’s largest single-site CSP facility.

Three Gorges Dam

China’s monster mountain dam

The Three Gorges Dam on China’s Yangtza river might be the world’s most powerful hydropower dam with its massive 22.5 GW capacity, but a different Chinese dam holds the title of the world’s tallest.

Jinping-I Hydropower Station is a 305-metre-tall arch dam on the Yalong River. It sits on the Jinping Bend where the river wraps around the entire Jinping mountain range. The project began in 2005 and was completed with the commissioning of a sixth and final generator in 2014, which brought its total capacity to 3.6 GW.

Itaipu Dam and hydropower station

Brazil and Paraguay’s river arrangement

While it may be tall, at 568 metres-long, Jinping-I is far from the longest. That mantle belongs to the 7,919 metre-long Itaipu Dam and hydropower station that straddles Brazil and Paraguay and has an installed capacity of 14 GW.

The power station is home to 20, 700 MW generators, however, as Brazil’s electricity system runs at 60Hz and Paraguay’s at 50Hz, 10 of the generators run at each frequency.

Biomass domes that could hide the Albert Hall

Using a relatively new material, such as compressed wood pellets as a renewable alternative to coal in large thermal power stations creates new challenges. Biomass ‘ecostore’ domes help tackle storage problems by keeping the materials dry and maintaining the right temperatures and conditions.

Unlike cylindrical, concrete silos, domes also offer greater resistance to hurricanes and extreme weather. This is important in areas such as Louisiana where this low carbon fuel is stored at the Drax Biomass port facility in 35.7 metre high, 61.6 metre diameter domes before it is shipped to Drax Power Station.

The power station itself is home to four of the world’s largest biomass domes. Each is 50.3 metres high and 63 metres in diameter – enough to hold the Albert Hall, or in Drax’s case 71,000 tonnes of biomass.

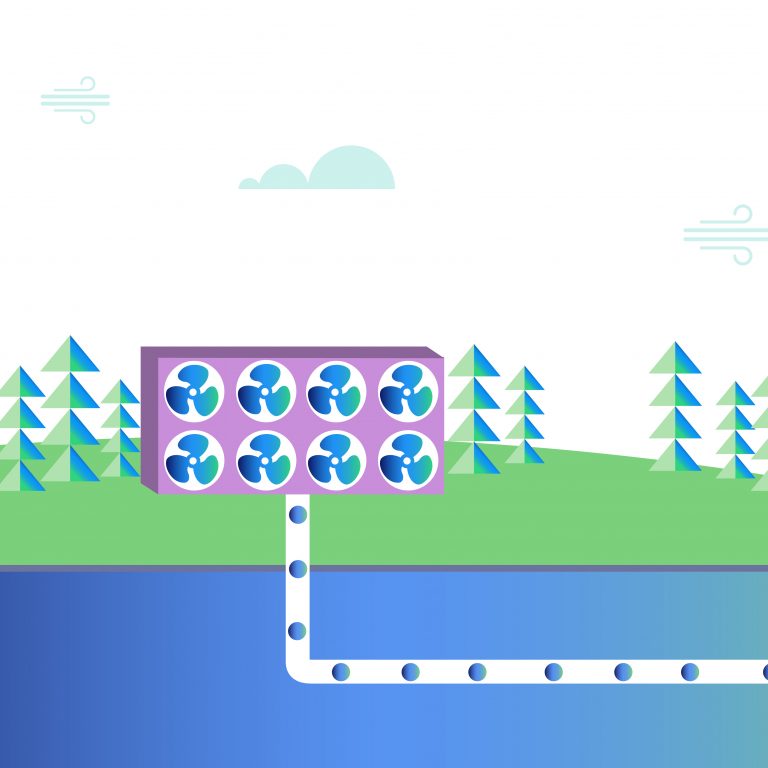

South Korean coastline takes the most from the tides

Beginning operation 1966, the Rance Tidal Power Station, in France was the first and largest facility of its kind for 45 years. The power station made use of the 750 metre-long Rance Barrage on France’s northern coast with a 330-metre-long section of it generating electricity through 24, 10 MW turbines.

It was overtaken, however, in 2011 with the opening of the Sihwa Lake Tidal Power Station in South Korea. The facility generates power along a 400-metre section of the 12.7 km Sihwa Lake tidal barrage and generates a maximum of 254 MW through ten 25.4 MW submerged turbines.

The battle to beat Tesla’s giant battery

South Australia has become a battlefield in the race to build the world’s biggest grid scale storage solution. Tesla constructed a 10,000 m2, football pitch-sized 100 MW lithium-ion battery outside of Adelaide at the end of 2017 which is connected to a wind power plant and can independently supply electricity to 30,000 homes for an hour.

However, rival billionaire to Tesla’s Elon Musk, Sanjeev Gupta plans to take on the storage facility with a 140 MW battery to support a new solar-powered steelworks, also in South Australia.

The excitement around battery technology’s potential means the title of world’s biggest will likely swap hands plenty more times over the next decade. This contest won’t just be confined to batteries. As countries increasingly move away from fossil fuels, bigger, wider and taller renewable structures will be needed to power the world. These are the world’s largest renewable structures today, but they probably won’t stay in those positions for long.