View here

View here

Electricity systems around the world are decarbonising and increasingly switching to renewable power sources. While intermittent sources, such as solar and wind, are the fastest growing types of renewables being installed globally, the reliability and flexibility of biomass and its ability to offer grid stabilisation services such as frequency control and inertia make it an increasingly necessary source of renewable power. According to the International Energy Agency biomass generation is forecast to expand as planned projects come online.

Biomass comes in many different forms. When looking to assess future demand and use, it is important to recognise benefits that different types of biomass bring. Compressed wood pellets are just one small part of the biomass spectrum, which includes many forms of agricultural and livestock residues, waste and bi-products – much of which is currently discarded or underutilised.

Maximising the use of these wastes and residues provides plenty of scope for expansion of the biomass energy sector around the world. The global installed capacity for biomass generation is expected to reach close to 140 gigawatts (GW) by 2026, which will be fuelled primarily by expansion in Asia using residues from food production and the forestry processing industry.

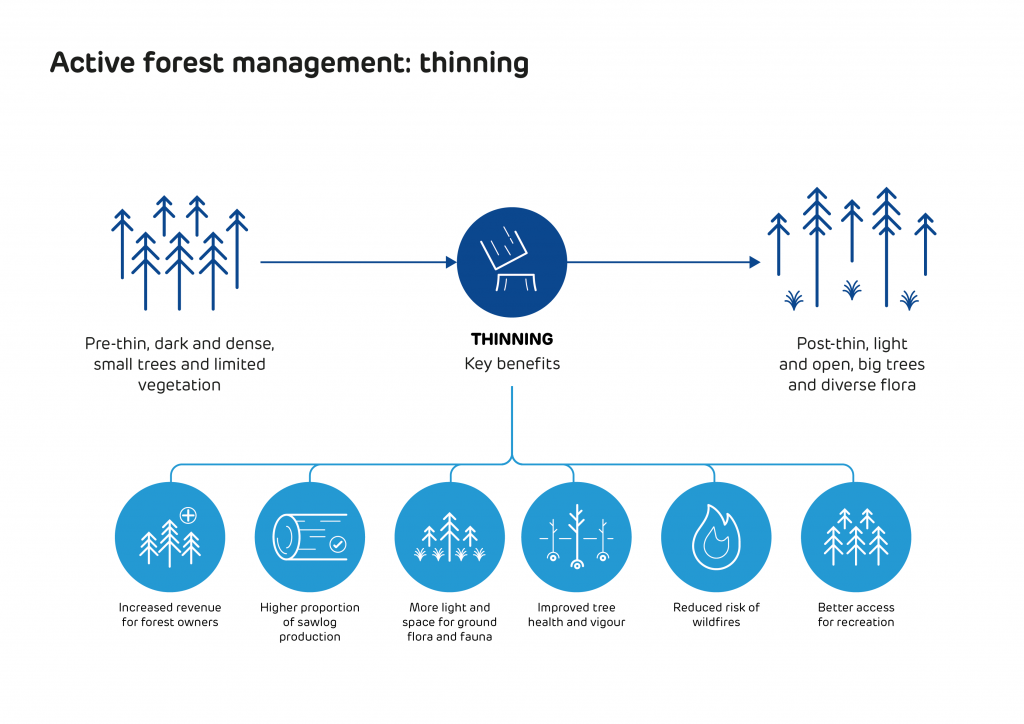

However, the use of woody biomass can also provide many benefits too, such as supplying a market for thinnings, providing a use for harvesting residues, encouraging better forest management practices and generating increased revenue for forest owners.

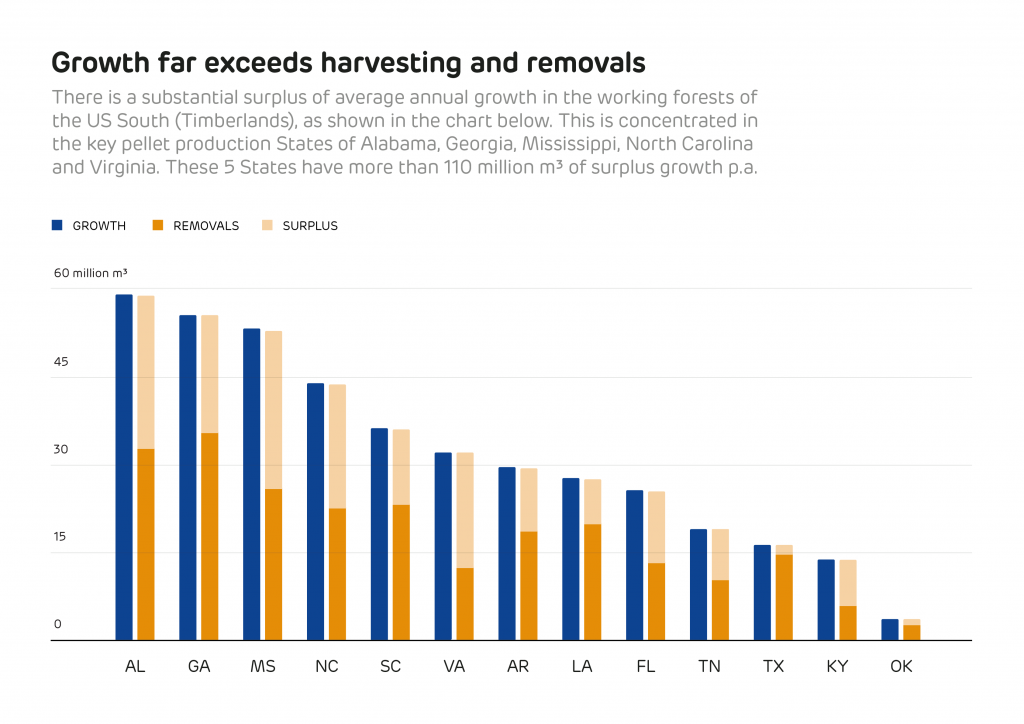

In areas like the US South, traditional markets for forest products have declined, whilst forest growth has significantly increased. According to the USDA Forest Inventory and Analysis (FIA) data, there is an average annual surplus of growth in the US South of more than 176 million cubic metres compared to removals – that’s enough to make around 84 million tonnes of wood pellets a year, from just one supply region.

Of course, not all of this surplus growth could or should be used for bio-energy, much of it is suitable for high value markets like saw-timber or construction and some of it is located on inaccessible or protected sites. However, new and additional markets are essential to maintain the health of the forest resource and to encourage forest owners to retain and maintain their forest assets.

In the current wood pellet supply regions for Europe, Pöyry management consulting has calculated that there is a surplus of low grade wood fibre and residues that could make an additional 140 million tonnes of wood pellets each year.

Compressed wood pellets on a conveyor belt

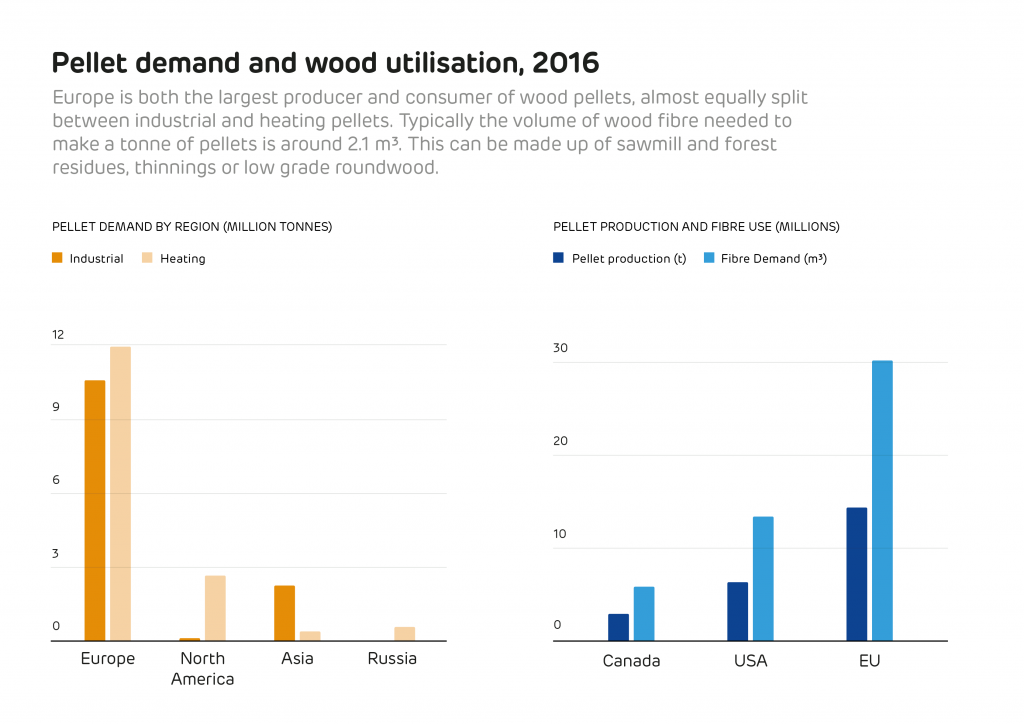

It is also necessary to look at the global production of all wood products to put wood pellet production into context. In 2016 the global production of industrial roundwood (the raw material used for construction, furniture, paper and other wood products) was 1.87 billion cubic metres, while the global production of wood fuel (used for domestic heating and cooking) was 1.86 billion cubic metres[1]. Only around 1.6% of this feedstock was used to make wood pellets, both for industrial energy and residential heat. The total production of wood pellets in 2016 was 28.4 million tonnes, of which only 45% was used for industrial energy[2].

While Forestry consulting and research firm Forisk predicts demand for industrial wood pellets (those used in electricity generation rather than residential heating) will grow globally at an annual rate of 15% for the next five years, reaching 27.5 megatonnes (Mt) by 2023, they are also clear that this growth, in context, will not impact forest volumes or other markets:

‘The wood pellet industry in the US South is not exploding, it is a tiny component of the overall market. Forest volumes in the South in total will continue to grow for decades no matter what bioenergy markets or housing markets do. The wood pellet sector simply and unequivocally cannot compete economically with US pulp and paper mills (80% of pulpwood demand in South) for raw material on a head-to-head basis[3].’

So, while demand for wood pellets is likely to increase over the next 10 years, this increase will be well within the scope of existing surplus fibre. The question, therefore, is can suppliers keep up with this demand? And can they do this while ensuring it remains sustainable, reliable and renewable?

In the short-term, intelligence firm Hawkins Wright estimates global demand will increase by almost 30% during 2018 to reach 20.4 Mt, while Forisk predicts a smaller jump: an almost 5 Mt increase compared to 2017.

Most of this will continue to come from Europe (73% of global demand by 2021, more than 80% in 2018), where projects such as Lynemouth Power Station’s conversion from coal to biomass, as well as five co-firing units in the Netherlands are all set to come online very soon. While smaller in number, Asia is also developing a growing appetite for biomass and in 2018 demand is forecast to grow by 1.98 Mt.

These estimates might paint a picture of a continually soaring demand, but Forisk’s forecast actually expect this growth to plateau, levelling off around 2023 at 27.5 Mt. Hawkins Wright expects a similar slow down, forecasting manageable growth of under 15% between 2023 and 2026.

A forestry specialist at Drax Group, believes this plateau could come even sooner.

“Current and future forecasts in industrial wood pellet demand are based on a series of planned conversions and projects coming online,” he explains.

“But once these projects are active, demand in Europe will likely plateau around 2021 and then gradually reduce as various EU support schemes for industrial biomass come to an end. Any long term use of biomass is likely to be based on agricultural residues and wastes.”

But even with this expected slowdown, the biomass demand of the near future will be substantially higher than it is right now. So, the question remains, can suppliers meet the need for biomass pellets?

Meeting this growing demand depends on two factors: sufficient raw materials and the production capabilities to turn those materials into biomass pellets.

In today’s market, there’s no shortage of raw materials and low grade fibre. Instead, what could cause challenges is the production of pellets.

Hawkins Wright reports the capacity for global industrial pellet production was roughly 21.4 Mt a year at the end of 2017 and will increase by a further 3 Mt by 2019 as facilities currently under construction reach completion.

It means that to meet even Forisk’s conservative 27.5 Mt prediction by 2023, pellet production needs to increase. However, Drax’s forestry specialist points to the three to four years needed to complete pellet facilities and the relatively short period of time financial support programmes will remain in place as something that could lead to a slowdown in new plants coming online. Instead, he says, expansions of existing plants and the increased use of small-scale facilities will become crucial to increasing overall production.

However the biomass market changes and develops, it remains critical that proper regulation is in place, efficiencies are found and that technological innovation continues within the forestry industry so forests are grown and managed sustainably.

As we move into a low-carbon future we know that biomass demand will increase. But for this to be truly beneficial and sustainable we need to ensure we are not only meeting the demand of today but also of tomorrow, the day after tomorrow and beyond.

[1] Source: FAOSTAT

[2] Source: Hawkins Wright, The Outlook for Wood Pellets, Q4 2017

[3] https://www.forisk.com/blog/2015/10/23/nibbling-on-a-chicken-or-nibbling-on-an-elephant-another-example-of-incomplete-and-misleading-analysis-of-us-forest-sustainability-and-wood-bioenergy-markets/

In 2013, Drax co-founded the SBP together with six other energy companies.

SBP builds upon existing forest certification programmes, such as the Sustainable Forest Initiative (SFI), Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) and the Programme for the Endorsement of Forest Certification (PEFC). These evidence sustainable forest management practices but do not yet encompass regulatory requirements for reporting greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. This is a critical gap for biomass generators, who are obligated to report GHG emissions to European regulators.

There is also limited uptake of forest-level certification schemes in some key forest source areas. SBP is working to address these challenges.

SBP certification provides assurance that woody biomass is supplied from legal and sustainable sources and that all regulatory requirements for the users of biomass for energy production are met. The tool is a unique certification scheme designed for woody biomass, mostly in the form of wood pellets and wood chips, used in industrial, large-scale energy production.

SBP certification is achieved via a rigorous assessment of wood pellet and wood chip producers and biomass traders, carried out by independent, third party certification bodies and scrutinised by an independent technical committee.

A truck arrives at an industrial facility deep in the expanding forestland of the south-eastern USA. It passes through a set of gates, over a massive scale, then onto a metal platform.

The driver steps out and pushes a button on a nearby console. Slowly, the platform beneath the truck tilts and rises. As it does, the truck’s cargo empties into a large container behind it. Two minutes later it’s empty.

This is how you unload a wood fuel truck at Drax Biomass’ compressed wood pellet plants in Louisiana and Mississippi.

“Some people call them truck dumpers, but it depends on who you talk to,” says Jim Stemple, Senior Director of Procurement at Drax Biomass. “We just call it the tipper.” Regardless of what it’s called, what the tipper does is easy to explain: it lifts trucks and uses the power of gravity to empty them quickly and efficiently.

The sight of a truck being lifted into the air might be a rare one across the Atlantic, however at industrial facilities in the United States it’s more common. “Tippers are used to unload trucks carrying cargo such as corn, grain, and gravel,” Stemple explains. “Basically anything that can be unloaded just by tipping.”

Both of Drax Biomass’ two operational pellet facilities (a third is currently idle while being upgraded) use tippers to unload the daily deliveries of bark – known in the forestry industry as hog fuel, which is used to heat the plants’ wood chip dryers – sawdust and raw wood chips, which are used to make the compressed wood pellets.

The tipper uses hydraulic pistons to lift the truck platform at one end while the truck itself rests against a reinforced barrier at the other. To ensure safety, each vehicle must be reinforced at the very end (where the load is emptying from) so they can hold the weight of the truck above it as it tips.

Each tipper can lift up to 60 tonnes and can accommodate vehicles over 50 feet long. Once tipped far enough (each platform tips to a roughly 60-degree angle), the renewable fuel begins to unload and a diverter guides it to one of two places depending on what it will be used for.

“One way takes it to the chip and sawdust piles – which then goes through the pelleting process of the hammer mills, the dryer and the pellet mill,” says Stemple. “The other way takes it to the fuel pile, which goes to the furnace.”

The furnace heats the dryer which ensures wood chips have a moisture level between 11.5% and 12% before they go through the pelleting process.

“If everything goes right you can tip four to five trucks an hour,” says Stemple. From full and tipping to empty and exiting takes only a few minutes before the trucks are on the road to pick up another load.

Using the power of gravity to unload a truck might seem a rudimentary approach, but it’s also an efficient one. Firstly, there’s the speed it allows. Multiple trucks can arrive and unload every hour. And because cargo is delivered straight into the system, there’s no time lost between unloading the wood from truck to container to system.

Secondly, for the truck owners, the benefits are they don’t need to carry out costly hydraulic maintenance on their trucks. Instead, it’s just the tipper – one piece of equipment – which is maintained to keep operations on track.

However, there is one thing drivers need to be wary of: what they leave in their driver cabins. Open coffee cups, food containers – anything not firmly secured – all quickly become potential hazards once the tipper comes into play.

“I guess leaving something like that in the cab only happens once,” Stemple says. “The first time a trucker has to clean out a mess from his cab is probably the last time.”