Key points

- Carbon capture usage and storage (CCUS) offers a unique opportunity to capture and store the UK’s emissions and help the country reach its climate goals.

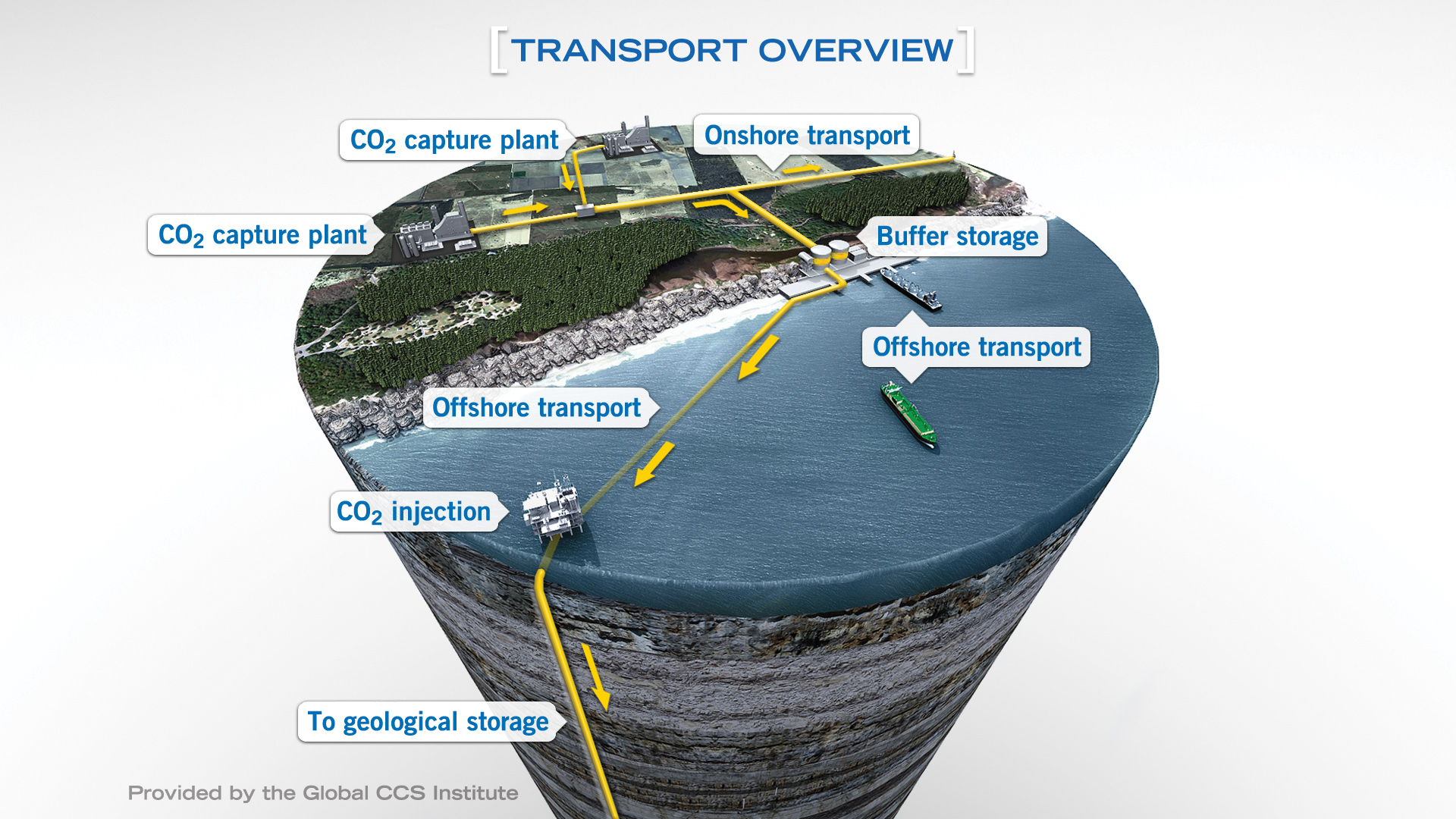

- Carbon dioxide (CO2) can be stored in geological reservoirs under the North Sea, but getting it from source to storage will need a large and safe CO2 transportation network.

- The UK already has a long history and extensive infrastructure for transporting gas across the country for heating, cooking and power generation.

- This provides a foundation of knowledge and experience on which to build a network to transport CO2.

Across the length of the UK is an underground network similar to the trainlines and roadways that crisscross the country above ground. These pipes aren’t carrying water or broadband, but gas. Natural gas is a cornerstone of the UK’s energy, powering our heating, cooking and electricity generation. But like the country’s energy network, the need to reduce emissions and meet the UK’s target of net zero emissions by 2050 is set to change this.

Today, this network of pipes takes fossil fuels from underground formations deep beneath the North Sea bed and distributes it around the UK to be burned – producing emissions. A similar system of subterranean pipelines could soon be used to transport captured emissions, such as CO2, away from industrial clusters around factories and power stations, locking them away underground, permanently and safely.

Conveyer system at Drax Power Station transporting sustainable wood pellets

The rise of CCUS technology is the driving force behind CO2 transportation. The process captures CO2 from emissions sources and transports it to sites such as deep natural storage enclaves far below the seabed.

Bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS) takes this a step further. BECCS uses sustainable biomass to generate renewable electricity. This biomass comes from sources, such as forest residues or agricultural waste products, which remove CO2 from the atmosphere as they grow. Atmospheric CO2 released in the combustion of the biomass is then captured, transported and stored at sites such as deep geological formations.

Across the whole BECCS process, CO2 has gone from the atmosphere to being permanently trapped away, reducing the overall amount of CO2 in the atmosphere and delivering what’s known as negative emissions.

BECCS is a crucial technology for reaching net zero emissions by 2050, but how can we ensure the CO2 is safely transported from the emissions source to storage sites?

Moving gases around safely

Moving gases of any kind through pipelines is all about pressure. Gases always travel from areas of high pressure to areas of low pressure. By compressing gas to a high pressure, it allows it to flow to other locations. Compressor stations along a gas pipeline help to maintain right the pressure, while metering stations check pressure levels and look out for leaks.

The greater the pressure difference between two points, the faster gases will flow. In the case of CO2, high absolute pressures also cause it to become what’s known as a supercritical fluid. This means it has the density of a liquid but the viscosity of a gas, properties that make it easier to transport through long pipelines.

Since 1967 when North Sea natural gas first arrived in the UK, our natural gas transmission network has expanded considerably, and is today made up of almost 290,000 km of pipelines that run the length of the country. Along with that physical footprint is an extensive knowledge pool and a set of well-enforced regulations monitoring their operation.

While moving gas through pipelines across the country is by no means new, the idea of CO2 transportation through pipelines is. But it’s not unprecedented, as it has been carried out since the 1980s at scale across North America. In contrast to BECCS, which would transport CO2 to remove and permanently store emissions, most of the CO2 transport in action today is used in oil enhanced recovery – a means of ejecting more fossil fuels from depleted oil wells. However, the principle of moving CO2 safely over long distances remains relevant – there are already 2,500 km of pipelines in the western USA, transporting as much as 50 million tonnes of CO2 a year.

“People might worry when there is something new moving around in the country, but the science community doesn’t have sleepless nights about CO2 pipelines,” says Dr Hannah Chalmers, from the University of Edinburgh. “It wouldn’t explode, like natural gas might, that’s just not how the molecule works. If it’s properly installed and regulated, there’s no reason to be concerned.”

CO2 is not the same as the methane-based natural gas that people use every day. For one, it is a much more stable, inert molecule, meaning it does not react with other molecules, and it doesn’t fuel explosions in the same way natural gas would.

CO2 has long been understood and there is a growing body of research around transporting and storing it in a safe efficient way that can make CCUS and BECCS a catalyst in reducing the UK’s emissions and future-proofing its economy.

Working with CO2 across the UK

Working with CO2 while it is in a supercritical state mean it’s not just easier to move around pipes. In this state CO2 can also be loaded onto ships in very large quantities, as well as injected into rock formations that once trapped oil and gas, or salt-dense water reserves.

Decades of extracting fossil fuels from the North Sea means it is extensively mapped and the rock formations well understood. The expansive layers of porous sandstone that lie beneath offer the UK an estimated 70 billion tonnes of potential CO2 storage space – something a number of industrial clusters on the UK’s east coast are exploring as part of their plans to decarbonise.

Source: CCS Image Library, Global CCS Institute [Click to view/download]

“Much of the research and engineering has already been done around the infrastructure side of the project,” explains Richard Gwilliam, Head of Cluster Development at Drax. “Transporting and storing CO2 captured by the BECCS projects is well understood thanks to extensive engineering investigations already completed both onshore and offshore in the Yorkshire region.”

This also includes research and development into pipes of different materials, carrying CO2 at different pressures and temperatures, as well as fracture and safety testing.

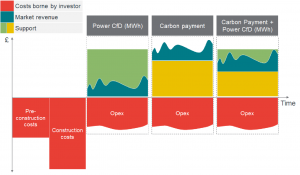

The potential for the UK to build on this foundation and progress towards net zero is considerable. However, for it to fully manifest it will need commitment at a national level to building the additional infrastructure required. The results of such a commitment could be far reaching.

In the Humber alone, 20% of economic value comes from energy and emissions-intensive industries, and as many as 360,000 jobs are supported by industries like refining, petrochemicals, manufacturing and power generation. Putting in place the technology and infrastructure to capture, transport and store emissions will protect those industries while helping the UK reach its climate goals.

It’s just a matter of putting the pipes in place.