Key takeaways:

- Tracking, reporting, and calculating carbon emissions are a key part of progressing countries, industries, and companies towards net zero goals.

- As a newly established discipline, carbon accounting still lacks standardisation and frameworks in how emissions are tracked, reduced, and mitigated.

- The main carbon accounting standard used by businesses is the Greenhouse Gas (GHG) Protocol, which lays out three ‘Scopes’ businesses should report and act upon.

- Carbon accounting evolves from reporting in the use of goals and timeframes in which targets are met.

- Timeframes are crucial in the deployment of technologies like carbon capture, removals, and achieving net zero.

How can countries and companies find a route to net zero emissions? Many organisations, countries and industries have pledged to balance their emissions before mid-century. They intend to do this through a combination of cutting emissions and removing carbon from the atmosphere.

Tracking and quantifying emissions, understanding output, reducing them, and setting tangible targets that can be worked towards are all central to tackling climate change and reducing greenhouse gas emissions – especially when it comes to carbon dioxide (CO2). Emissions and energy consumption reporting is already common practice and compulsory for businesses over a certain size in the UK. However, carbon accounting takes this a step further.

“Carbon reporting is a statement of physical greenhouse gas emissions that occur over a given period,” explains Michael Goldsworthy, Head of Climate Change and Carbon Strategy at Drax. “Carbon accounting relates to how those emissions are then processed and counted towards specific targets. The methodologies for calculating emissions and determining contributions against targets may then have differing rules depending on which framework or standard is being reported against.”

Carbon accounting tools can help companies and counties understand their carbon footprint – how much carbon is being emitted as part of their operations, who is responsible for them, and how they can be effectively mitigated.

Like how financial accounting may seek to balance a company’s books and calculate potential profit, carbon accounting seeks to do the same with emissions, tracking what an entity emits, and what it reduces, removes, or mitigates. Carbon accounting is, therefore, crucial in understanding how countries and companies can contribute to reaching net zero.

A new space

How different organisations, countries and industries approach carbon accounting is still an evolving process.

“It’s as complex as financial accounting, but with financial accounting, there’s a long standing industry that relies on well-established practices and principles. Carbon accounting by contrast is such a new space,” explains Goldsworthy.

Regardless of its infancy, businesses and countries are already implementing standardised approaches to carbon accounting. Regulations such as emissions trading schemes and reporting systems, such as Streamlined Energy and Carbon Reporting (SECR) and the Taskforce on Climate Related Financial Disclosure (TCFD), are beginning to deliver some degree of consistency in businesses’ carbon reporting.

Other standards such as the GHG Protocol have sought to provide a standardised basis for corporate reporting and accounting. Elsewhere, voluntary carbon markets (e.g. carbon offsets) have also evolved to allow transferral of carbon reductions or removals between businesses, providing flexibility to companies in delivering their climate commitments.

The challenge is in aligning these frameworks so that they work together. For example, emissions within a corporate inventory or offset programme must be accounted for in a way that is consistent with a national inventory.

To date, these accounting systems have evolved independently with different rules and methodologies. Beginning to implement detailed carbon accounting, upon which emissions reductions and removals can be based, requires standardised understanding of what they are and where they come from.

Reporting and tackling Scope One, Two, and Three emissions

The main carbon accounting standard used by businesses is the Greenhouse Gas (GHG) Protocol. This voluntary carbon reporting standard can be used by countries and cities, as well as individual companies globally.

The GHG protocol categorises emissions in three different ‘scopes’, called Scope 1, Scope 2, and Scope 3. Understanding, measuring, and reporting these is a key factor in carbon accounting and can drive meaningful emissions reduction and mitigation.

Scope One – Direct emissions

Scope One emissions are those that come as a direct result of a company or country’s activities. These can include fuel combustion at a factory’s facilities, for example, or emissions from a fleet of vehicles.

Scope One emissions are the most straightforward for an organisation to measure and report, and easier for organisations to directly act on.

Scope Two – Indirect energy emissions

Scope Two emissions are those which come from the generation of energy an organisation uses. These can include emissions form electricity, steam, heating, and cooling.

Scope Two emissions are those which come from the generation of energy an organisation uses. These can include emissions form electricity, steam, heating, and cooling.

A business may buy electricity, for example, from an electricity supplier, which acquires power from a generator. If that generator is a fossil-fuelled power station the energy consumer’s Scope Two emissions will be greater than if it buys power from a renewable electricity supplier or generates its own renewable power.

The ability to change energy suppliers makes Scope Two relatively straightforward for organisations to act on, assuming renewable energy sources are available in the area.

Scope Three – All other indirect emissions

Scope Three is much broader. It covers upstream and downstream lifecycle emissions of products used or produced by a company, as well as other indirect emissions such as employee commuting and business travel emissions.

Identifying and reducing these emissions across supply and value chains can be difficult for businesses with complex supply lines and global distribution networks. They are also hard for companies to directly influence.

Add in factors like emissions mitigations or offsetting, and the carbon accounting can quickly become much more complex than simply reporting and reducing emissions that occur directly from a company’s activities. Nevertheless, these full-system overviews and whole-product lifecycle accounting are crucial to understanding the true impact of operations and organisations, and to reach climate goals.

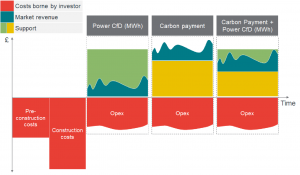

Working to timelines

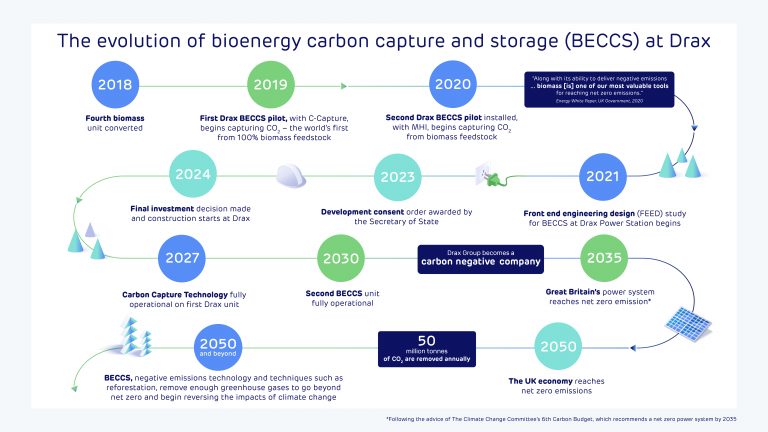

Setting goals with defined timelines and the development of rules that ensure consistent accounting is also crucial to implementing effective climate change mitigation frameworks throughout the global economy. Consider the UK’s aim to be net zero by 2050, or Drax’s ambition to be net negative by 2030, as goals with set timelines.

For many technologies, the time scales over which targets are set have added relevance. There are often upfront emissions to account for and operational emissions that may change over time. Take for example an electric vehicle: the climate benefit will be determined by emissions from construction and the carbon intensity of the electricity used to power it.

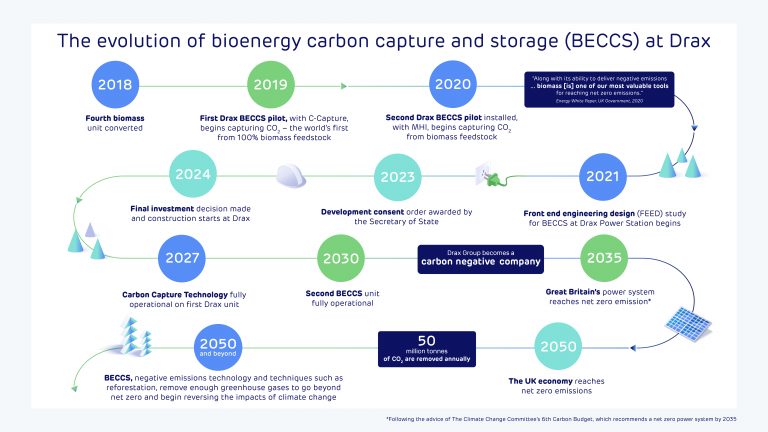

A timeline of BECCS at Drax [click to view/download]

Looking at a brief snapshot at the beginning of its life, say the first couple of years, might not show any climate benefit compared to a vehicle using an internal combustion engine. Over the lifetime of the vehicle, however, meaningful emissions savings may become clear – especially if the electricity powering the vehicle continues to decarbonise over time.

This provides a challenge when setting carbon emissions targets. Targets set too far in the future potentially risk inaction in the short term, while targets set over short periods risk disincentivising technologies that have substantial long-term mitigation potential.

Delivering net zero

Some greenhouse gas emissions will be impossible to fully abate, such as methane and nitrous oxide emissions from agriculture, while other sectors, like aviation, will be incredibly difficult to fully decarbonise. This makes carbon removal technologies all the more critical to ensuring net zero is achieved.

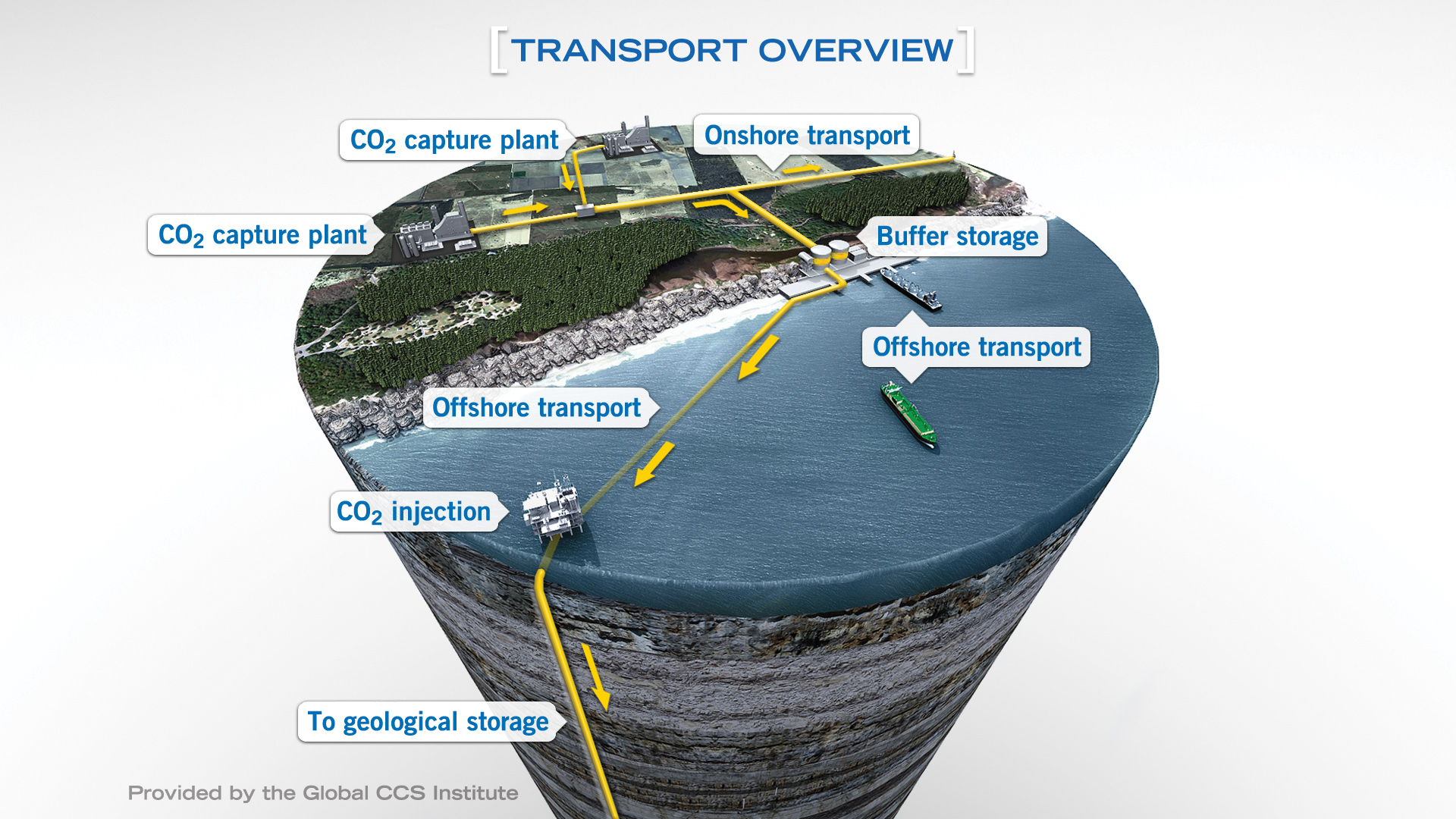

Technologies such as bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS) – which combines low-carbon, biomass-fuelled renewable power generation with carbon capture and storage (CCS) to permanently remove emissions from the atmosphere – are already under development.

However, it is imperative that such technologies are accounted for using robust approaches to carbon accounting, ensuring all emission and removals flows across the value chain are accurately calculated in accordance with best scientific practice. In the case of BECCS, it’s vital that not only are emissions from processing and transporting biomass considered, but also its potential impact on the land sector.

Forests from which biomass is sourced will be managed for a variety of reasons, such as mitigating natural disturbance, delivering commercial returns, and preserving ecosystems. Accurate accounting of these impacts is therefore key to ensuring such technologies deliver meaningful reductions in atmospheric CO2within timeframes guided by science.

Accounting for net zero

While carbon accounting is crucial to reaching a true level of net zero in the UK and globally, where residual emissions are balanced against removals, the practice should not be used exclusively to deliver numerical carbon goals.

“To deliver net zero, it’s vital we have robust carbon accounting systems and targets in place, ensuring we reduce fossil emissions as far as possible while also incentivising carbon removal solutions,” says Goldsworthy.

“However, many removal solutions rely on the natural world and so it is critical that ecosystems are not only valued on a carbon basis but consider other environmental factors such as biodiversity as well.”

Scope Two emissions are those which come from the generation of energy an organisation uses. These can include emissions form electricity, steam, heating, and cooling.

Scope Two emissions are those which come from the generation of energy an organisation uses. These can include emissions form electricity, steam, heating, and cooling.