The concept of capturing carbon dioxide (CO2) from power station, refinery and factory exhausts has long been hailed as crucial in mitigating the climate crisis and getting the UK and the rest of the world to net zero. After a number of false starts and policy hurdles, the technology is now growing with more momentum than ever. Carbon capture, use and storage (CCUS) is finally coming of age.

Increasing innovation and investment in the space is enabling the development of CCUS schemes at scale. Today, there are over 19 large-scale CCUS facilities in operation worldwide, while a further 32 in development as confidence in government policies and investment frameworks improves.

Once CO2 is captured it can be stored underground in empty oil and gas reservoirs and naturally occurring saline aquifers, in a process known as sequestration. It has also long been used in enhanced oil recovery (EOR), a process where captured CO2 is injected into oil reservoirs to increase oil production.

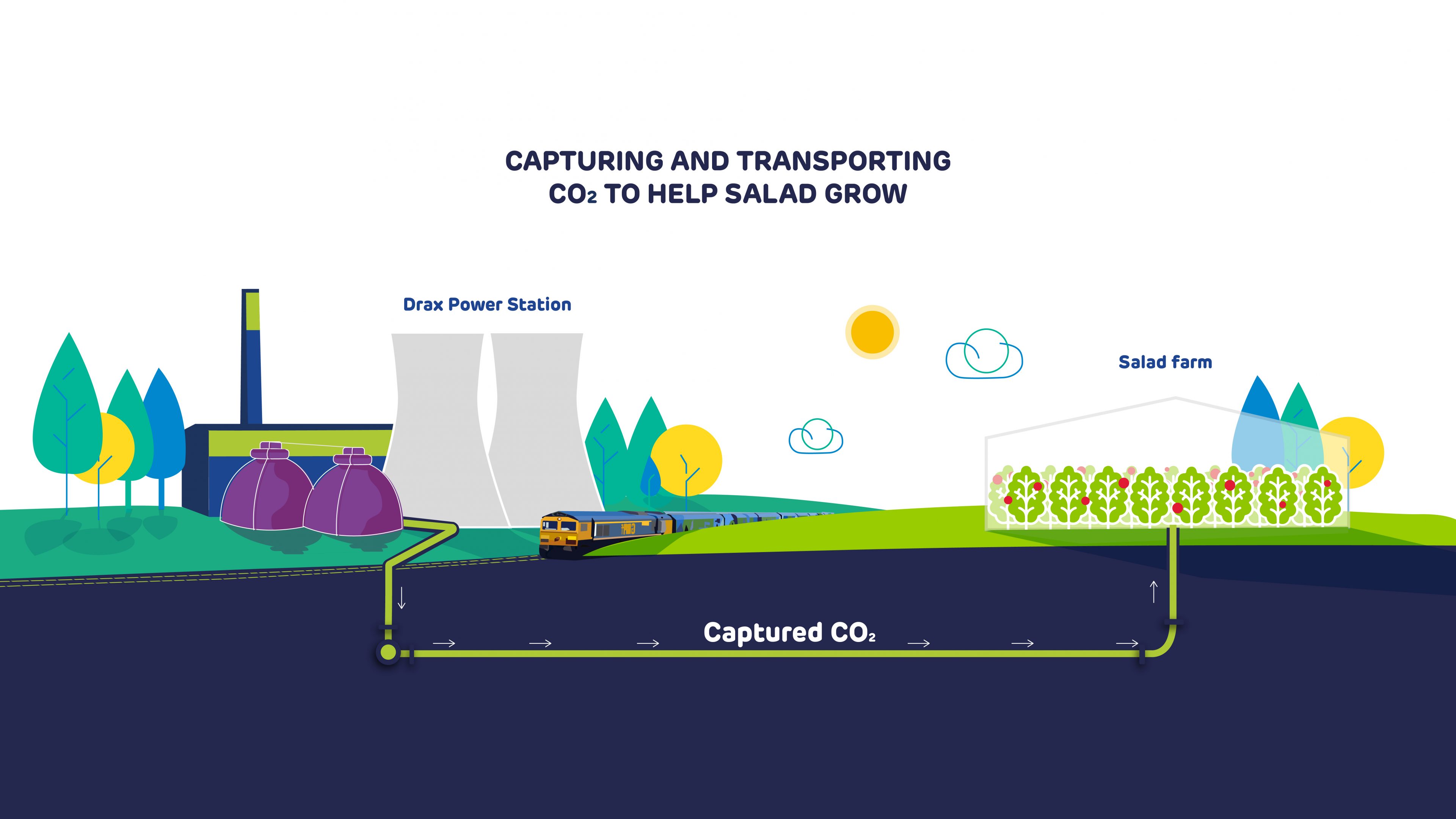

Drax Power Station is already trialling Europe’s first bioenergy carbon capture and storage (BECCS) project. This combination of sustainable biomass with carbon capture technology could remove and capture more than 16 million tonnes of CO2 a year and put Drax Power Station at the centre of wider decarbonisation efforts across the region as part of Zero Carbon Humber.

Here are five other projects making carbon capture a reality today:

Snøhvit & Sleipner Vest

Who: Sleipner – Equinor Energy, Var Energi, LOTOS, KUFPEC; Snøhvit – Equinor Energy, Petoro, Total, Neptune Energy, Wintershall Dean

Where: Norway

Sleipner Vest was the world’s first ever offshore carbon capture and storage (CCS) plant, and has been active since 1996. The facility separates CO2 from natural gas extracted from the Sleipner field, as well as from at the Utgard field, about 20km away. This method of carbon capture means CO2 is removed before the natural gas is combusted, allowing it to be used as an energy source with lower carbon emissions.Snøhvit, located offshore in Norway’s northern Barents Sea, operates similarly but here natural gas is pumped to an onshore facility for carbon removal. The separated and compressed CO2 from both facilities is then stored, or sequestered, in empty reservoirs under the sea.

The two projects demonstrate the safety and reality of long-term CO2 sequestration – as of 2019, Sleipner has captured and stored over 23 million tonnes of CO2 while Snøhvit stores 700,000 tonnes of CO2 per year.

Petra Nova

Who: NRG, Mitsubishi Heavy Industries America, Inc. (MHIA) and JX Nippon, a joint venture with Hilcorp Energy

Where: Texas, USA

In 2016, the largest carbon capture facility in the world began operation at the Petra Nova coal-fired power plant.

Using a solvent developed by Mitsubishi and Kansai Electric Power, called KS-1, the CO2 is absorbed and compressed from the exhausts of the plant after the coal has been combusted. The captured CO2 is then transported and used for EOR 80 miles away on the West Ranch oil field.

Carbon capture facility at the Petra Nova coal-fired power plant, Texas, USA

As of January 2020, over 3.5 million tonnes of CO2 had been captured, reducing the plant’s carbon emissions by 90%. Oil production, on the other hand, increased by 1,300% to 4,000 barrels a day. As well as preventing CO2 from being released into the atmosphere, CCUS has also aided the site’s sustainability by eliminating the need for hydraulic drilling.

Gorgon LNG

Who: Operated by Chevron, in a joint venture with Shell, Exxon Mobil, Osaka Gas, Tokyo Gas, Jera

Where: Barrow Island, Australia

In 2019 CCS operations began at one of Australia’s largest liquified natural gas production facilities, located off the Western coast. Here, CO2 is removed from natural gas before the gas is cooled to -162oC, turning it into a liquid.

The removed CO2 is then injected via wells into the Dupuy Formation, a saline aquifer 2km underneath Barrow Island.

Once fully operational (estimated to be in 2020), the project aims to reduce the facility’s emissions by about 40% and plans to store between 3.4 and 4 million tonnes of CO2 each year.

Quest

Shell’s Quest carbon capture facility, Alberta, Canada

Who: Operated by Shell, owned by Chevron and Canadian Natural Resources

Where: Alberta, Canada

The Scotford Upgrader facility in Canada’s oil sands uses hydrogen to upgrade bitumen (a substance similar to asphalt) to make a synthetic crude oil.

In 2015, the Quest carbon capture facility was added to Scotford Upgrader to capture the CO2 created as a result of making the site’s hydrogen. Once captured, the CO2 is pressurised and turned into a liquid, which is piped and stored 60km away in the Basal Cambrian Sandstone saline aquifer.

Over its four years of crude oil production, four million tonnes of CO2 have been captured. It is estimated that, over its 25-year life span, this CCS technology could capture and store over 27 million tonnes of CO2.

Chevron estimates that if the facility were to be built today, it would cost 20-30% less, a sign of the falling cost of the technology.

Boundary Dam

Who: SaskPower

Where: Saskatchewan, Canada

Boundary Dam, a coal-fired power station, became the world’s first post-combustion CCS facility in 2014.

The technology uses Shell’s Cansolv solvent to remove CO2 from the exhaust of one of the power station’s 115 MW units. Part of the captured CO2 is used for EOR, while any unused CO2 is stored in the Deadwood Formation, a brine and sandstone reservoir, deep underground.

As of December 2019, more than three million tonnes of CO2 had been captured at Boundary Dam. The continuous improvement and optimisations made at the facility are proving CCS technology at scale and informing CCS projects around the world, including a possible retrofit project at SaskPower‘s 305 MW Shand Power Station.

Top image: Carbon capture facility at the Petra Nova coal-fired power plant, Texas, USA

Learn more about carbon capture, usage and storage in our series:

- Planting, sinking, extracting – some of the ways to absorb carbon from the atmosphere

- Why experts think bioenergy with carbon capture and storage will be an essential part of the energy system

- The science of safely and permanently putting carbon in the ground

- The numbers must add up to enable negative emissions in a zero carbon future, says Drax Group CEO Will Gardiner.

- The power industry is leading the charge in carbon capture and storage but where else could the technology make a difference to global emissions?

- From NASA to carbon capture, chemical reactions could have a big future in electricity

- A roadmap for the world’s first zero carbon industrial cluster: protecting and creating jobs, fighting climate change, competing on the world stage

- Can we tackle two global challenges with one solution: turning captured carbon into fish food?

- How algae, paper and cement could all have a role in a future of negative emissions

- How the UK can achieve net zero

- Transforming emissions from pollutants to products

- Drax CEO addresses Powering Past Coal Alliance event in Madrid, unveiling our ambition to play a major role in fighting the climate crisis by becoming the world’s first carbon negative company