On the night of 5 December 2015, 61,000 homes and properties across Lancaster were plunged into darkness. Storm Desmond had unleashed torrents of rain on Great Britain, causing rivers to swell and spill over. With waters rising to unprecedented levels, the River Lune began threatening to flood Lancaster’s main electricity substation, the facility where transformers ‘step down’ electricity’s voltage from the transmission system so it can be distributed safely around the local area.

To prevent unrepairable damage, the decision was taken to switch the substation off, cutting all power across the region. Lights, phones, internet connections and ATMs all went dead across the city. It would take three days of intensive work before power was restored.

It was a bigger power outage than most, but it offers a unique glimpse into the mechanisms behind a blackout – not only how they’re dealt with, but how they’re caused.

What causes blackouts in Great Britain?

When the lights go out, a common thought is that the country has ‘run out’ of electricity. However, a lack of electricity generation is almost never the cause of outages. Only during the miners’ strikes of 1972 were major power cuts the result of lack of electricity production.

Rather than meeting electricity demand, power cuts in Great Britain are more often the result of disruption to the transmission system, caused by unpredictable weather. If trees or piles of snow bring down one power line, the load of electric current shifts to other lines. If this sudden jump in load is too much for the other lines they automatically trip offline to prevent damage to the equipment. This in turn shifts the load on to other lines which also then trip, potentially causing cascading outages across the network.

Last March’s ‘Beast from the East’, which brought six days of near sub-zero temperatures, deep snow and high winds to Great Britain, is an example of extreme weather cutting electricity to as many as 18,000 people.

High-winds brought trees and branches down onto powerlines, while ice and snow impacted the millions of components that make up the electricity system. Engineering teams had to fight the elements and make the repairs needed to get electricity flowing again.

Lancaster was different, however. With the slow creep of rising rainwater approaching the substation, the threat of long lasting damage was plain to see in advance, and so rather than waiting for it to auto-trip, authorities chose to manually shut it down.

Getting reconnected

Electricity North West is Lancaster’s network operator and after shutting down the substation, it began the intensive job of trying to restore power. On Monday 7 December, two days after the storm hit, the first step of pumping the flooded substation empty of water had finally been completed and the task of reconnecting it began.

To begin restoring power to the region 75 large mobile generators were brought from as far away as the West Country and Northern Ireland and hooked up to the substation, allowing 22,000 customers to be reconnected.

Once partial power was restored, the next challenge lay in repairing and reconnecting the substation to the transmission network. While shutting the facility had prevented catastrophic damage, some of the crucial pieces had to be completely replaced or rebuilt. After three days of intensive engineering work the remaining 40,000 properties that had lost power were reconnected.

Preventing blackouts in a changing system

The cause and scale of Lancaster’s outage were unusual for Great Britain’s electricity system but it does highlight how quickly a power cut may arise. In a time of transition, when the grid is decarbonising and the network is facing more extreme weather conditions because of climate change, it could create even more, new challenges.

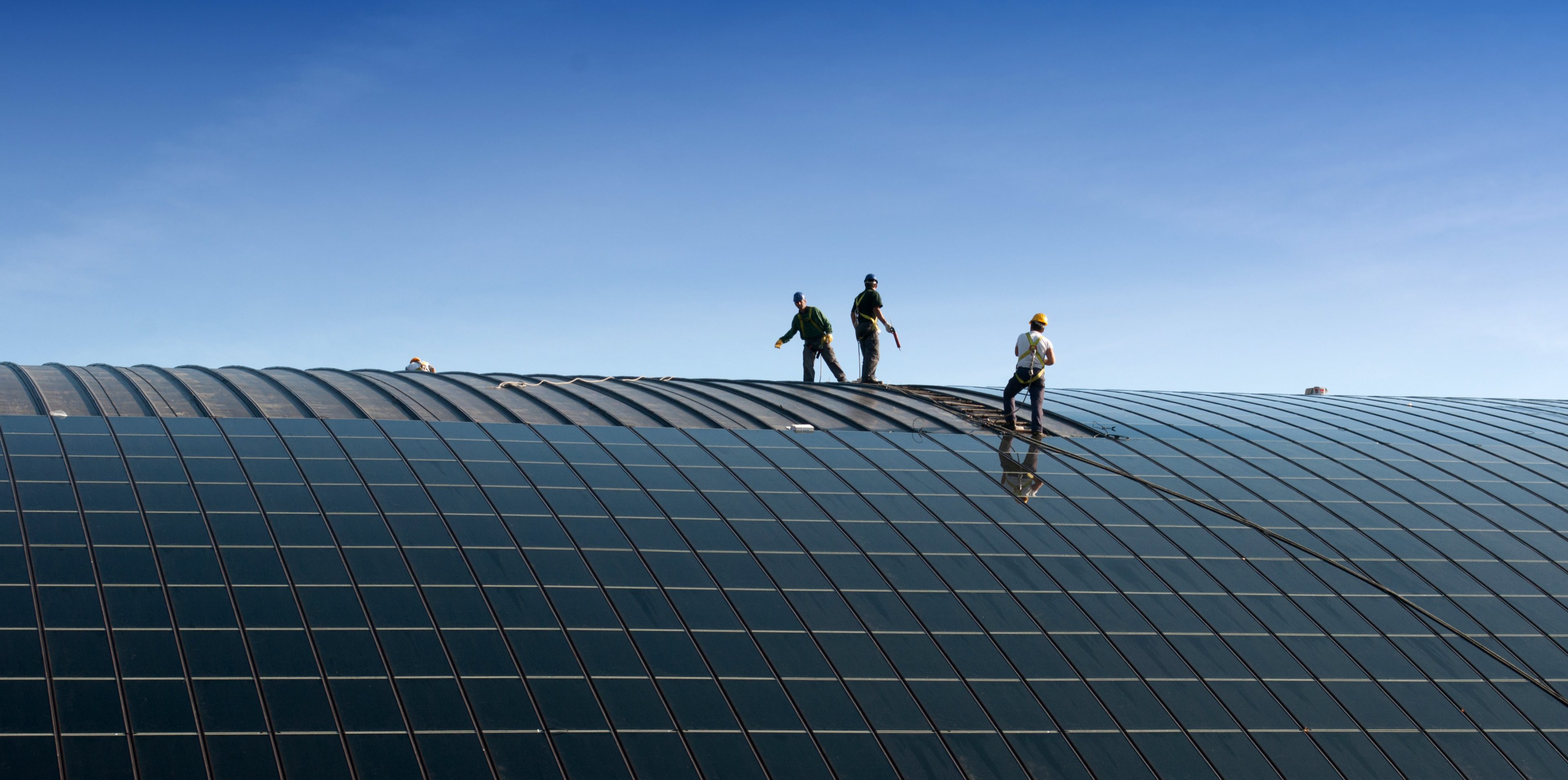

Coal is scheduled to be taken entirely off the system after 2025, making the country more reliant on weather-dependent sources, such as wind and solar – potentially increasing the volatility of the system.

On the other hand, growing decentralised electricity generation may reduce the number of individual buildings affected by outages in the future. Solar generation and storage systems present on domestic and commercial property may also reduce dependency on local transmission systems and the impact of disruptions to it.

The cables and poles that connect the transmission system will always be vulnerable to faults and disruptions. However, by preparing for the future grid Great Britain can reduce the impact of storms on the electricity system.