What does it mean to say Great Britain’s electricity network needs to be balanced? It doesn’t refer to the structural stability of pylons. Rather, balancing the power system is about ensuring electricity supply meets demand second by second.

From the side of a consumer, the power system serves one purpose: to deliver electricity to homes and businesses so that it powers our lives. But from a generator and a system operator perspective, there is much more at play.

Electricity must be transported the length of the country, levels of generation must be managed so they are exactly equal to levels being used, and properties like voltage and frequency must be minutely regulated across the whole network to ensure power generated at scale in industrial power stations can be used by domestic appliances plugged into wall sockets.

Ensuring all this happens smoothly relies on the system operator – National Grid – working with power generators to provide ‘ancillary services’ – a set of processes that keep the power system in operation, stable and balanced.

Here we look at some of the most important ancillary services at play in Great Britain.

Frequency response

Frequency response

One of the foundations of Great Britain’s power system stability is frequency. The entire power network operates at a frequency of 50 Hz, which is determined by the number of directional changes alternating current (AC) electricity makes every second. However, just a 1% deviation from this begins to damage equipment and infrastructure, so it is imperative it remains consistent.

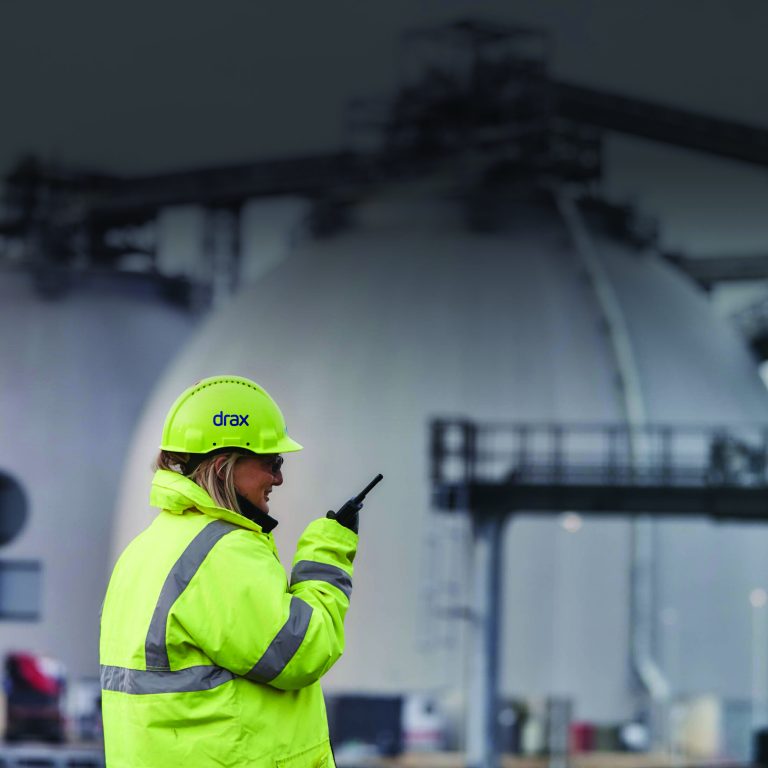

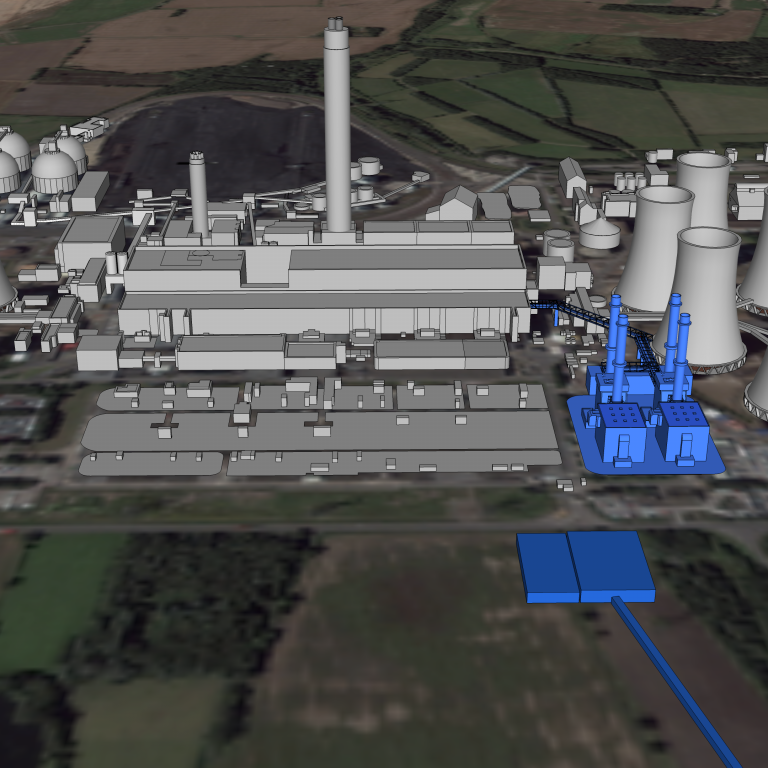

This is done by National Grid instructing flexible generators (such as thermal, steam-powered turbines like those at Drax Power Station or our planned battery facility) to either increase or decrease generation so electricity supply is matched exactly to demand. If this is unbalanced it affects the network’s frequency and lead to instability and equipment damage. Generators are set up to respond automatically to these request, correcting frequency deviations in seconds.

Reactive power and voltage management

Reactive power and voltage management

The electricity that turns on light bulbs and charges phones is what’s known as ‘active power’. However, getting that active power around the transmission system efficiently, economically and safely requires something called ‘reactive power’.

Reactive power is generated the same way as active power and assists with “pushing” the real power around the system but unlike active power it’s does not travel very far. The influence of Reactive power is local and the balance in any particular area is very important to maintain power flows and a stable system.

This means National Grid must work with generators to either generate more reactive power when there is not enough, or absorb it when there is an excess, which can happen when lines are ‘lightly loaded’ (meaning they have a low level of power running through them).

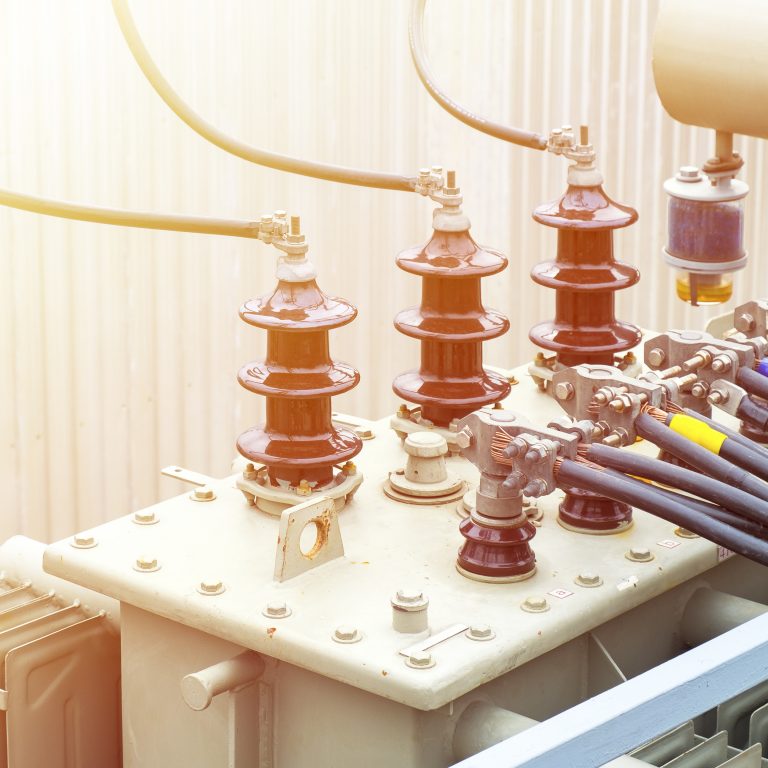

Drax’s ability to absorb reactive power is also vital in controlling the grid’s voltage. Great Britain’s system runs at a voltage of 400 kilovolts (kV) and 275 kV (Scotland also uses 132kV), before it is stepped down by transformers to 230 volts for homes or 11 kV for heavy industrial users. Voltage must stay within 5% of 400 kV before it begins to damage equipment.

By producing reactive power a generator increases the voltage on a system, but by switching to absorbing reactive power it can help lower the voltage, keeping the grid’s electricity safe and efficient.

System inertia

As well as being able to automatically adjust to keep the country on the right frequency, Drax’s massive turbines, spinning at 3,000 rpm, also have the advantage of adding inertia to the grid.

Inertia is an object’s natural tendency to keep doing what it is currently doing.

This system inertia of the spinning plant is effectively ‘stored’ energy. This can be used to act as a damper on the whole system to slow down and smooth out sudden changes in system frequency across the network – much like a car’s suspension it helps maintain stability.

Reserve power

Humans are creatures of habit. This means the whole country tends to load dishwashers, turn on TVs and boil kettles at roughly the same time each day, making the rise and fall in electricity demand easy enough for National Grid to predict.

However, if something unexpected happens – a sudden cold snap or a power station breaking down – the grid must be ready. For this, National Grid keeps reserve power on the system to jump into action and fill any sudden gaps in demand and fluctuations in voltage and frequency it could cause.

Ancillary services in an evolving system

As with how electricity is generated across the country, balancing services are undergoing major change. As more intermittent renewables, such as wind and solar, come onto the system to provide low carbon power necessary for Great Britain to decarbonise, that same system becomes more volatile and more difficult to balance.

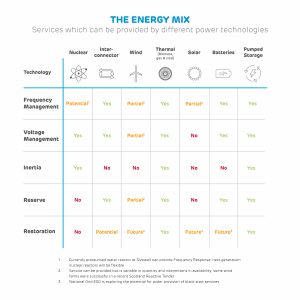

More than that, the ancillary services needed to stabilise a more volatile grid can’t be generated by every generation source. Many depend on a turbine rotating at 3,000 rpm, generating electricity at a steady frequency of 50Hz, as is found in thermal generators such as Drax. Intermittent, also known as variable sources of power, are weather dependent. They are often unable to provide the same services as biomass and gas power stations.

While attempts to supply some of these ancillary services by co-locating wind or solar facilities with giant batteries are underway, thermal power stations that can quickly and reliably balance the system at scale still play an essential role in making the transmission network safe, efficient, economic and stable.

This story is part of a series on the lesser-known electricity markets within the areas of balancing services, system support services and ancillary services. Read more about black start, system inertia, frequency response, reactive power and reserve power. Find out what lies ahead by reading Balancing for the renewable future and Maintaining electricity grid stability during rapid decarbonisation.