Every morning we take electricity as a given. We switch on lights, charge phones and boil kettles without thinking about where this power comes from.

The electronic devices and appliances that make up our daily routines are not particularly energy intensive. Boiling a kettle only uses 93 watts, toasting for three minutes only requires 60 watts, while cooking in a microwave for five minutes takes 100 watts.

However, when people are waking up and making breakfast in almost 30 million households around the UK, those small amounts soon create a significant demand for electricity. On a typical winter’s morning, this combined demand spikes to more than 45 gigawatts (GW).

So this is what it takes to power your breakfast – from the everyday toaster in your kitchen backwards through thousands of miles of cables to the hundreds of thousands of tonnes of machinery in wind farms, hydro-electric dams and at power stations such as Drax where electricity generation begins.

The grid

The journey starts in the home where all our electricity usage is tracked by meters. These are becoming increasingly ‘smart’, displaying near real-time information on energy consumption in financial terms and allowing more accurate billing. There are already 7.7 million smart meters installed around the UK, but that number is set to triple this year, paving the way for a smarter grid overall.

What brings electricity into homes is perhaps the most visible part of the energy system on the UK’s landscape. The transmission system is made up of almost 4,500 miles of overhead electricity lines, nearly 90,000 pylons and 342 substations, all bringing electricity from power stations into our homes.

Making sure all this happens safely and as efficiently as possible falls to the UK’s nine regional electricity networks and National Grid. Regional networks ensure all the equipment is in place and properly maintained to bring electricity safely across the country, while National Grid is tasked with making sure demand for electricity is met and that the entire grid remains balanced.

The station cools down

One of the most distinctive symbols of power generation, cooling towers carry out an important task on a massive scale.

Water plays a crucial role in electricity generation, but before it can be safely returned to the environment it must be cooled. Water enters cooling towers at around 40 degrees Celsius, and is cooled by air naturally pulled into the structure by its unique shape.

This means those plumes exiting from the top of the towers are, rather than any form of pollution, only water vapour. And this accounts for just 2% of the water pumped into the towers.

Drax counts 12 cooling towers, each 114 metres tall – enough to hold the Statue of Liberty with room to spare. Once the water is cooled it is safe to re-enter the nearby River Ouse.

The station’s bird’s-eye view

The control room is the nerve centre of Drax Power Station. From here technicians have a view into every stage of the power generation process. The entire system controls roughly 100,000 signals from across the power station’s six generating units, water cooling, air compressors and more.

While once this area was made up of analogue dials and controls, it has recently been updated and modernised to include digital interfaces, display screens and workstations specially designed by Drax to enable operators to monitor and adjust activity around the plant.

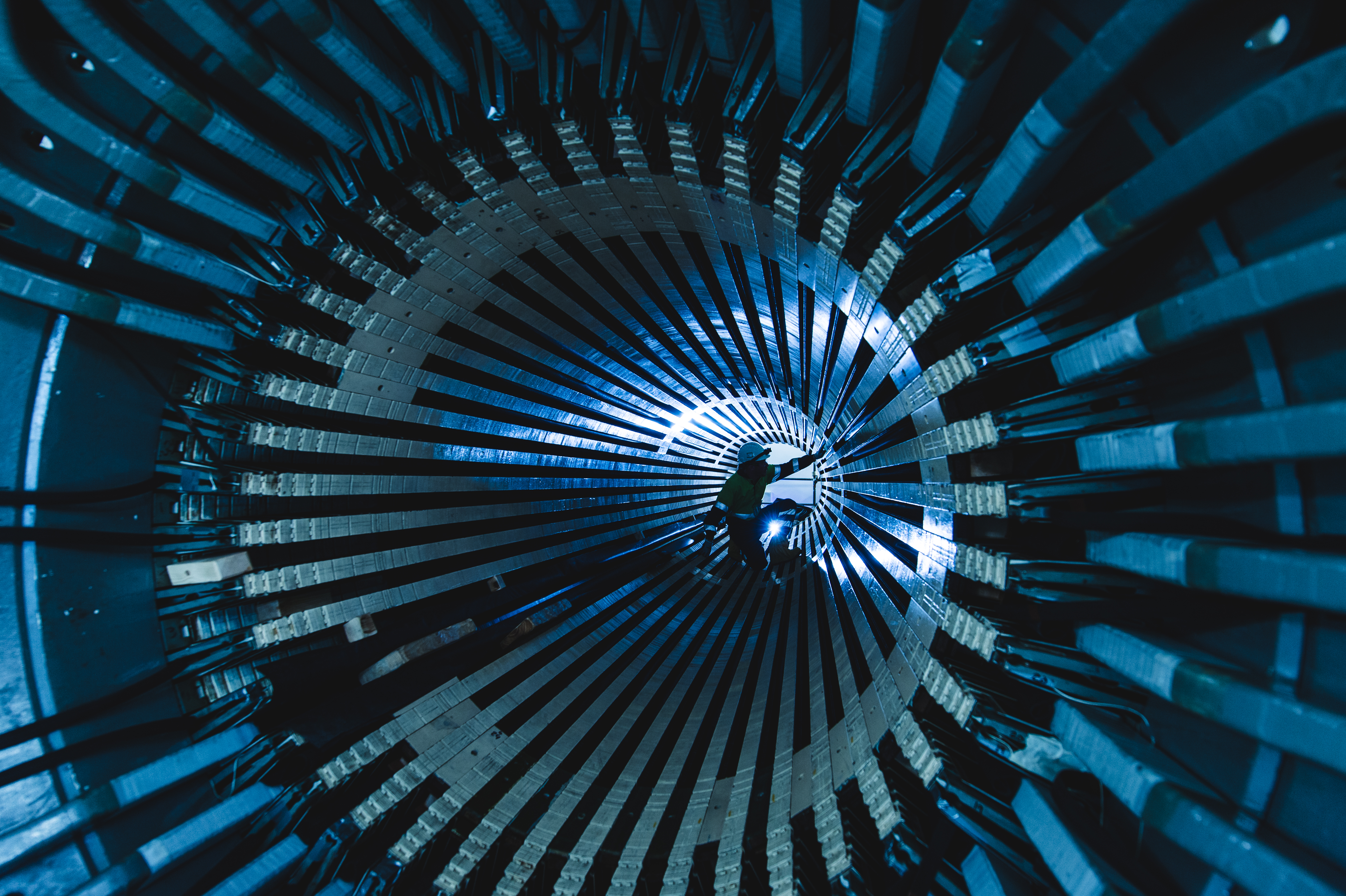

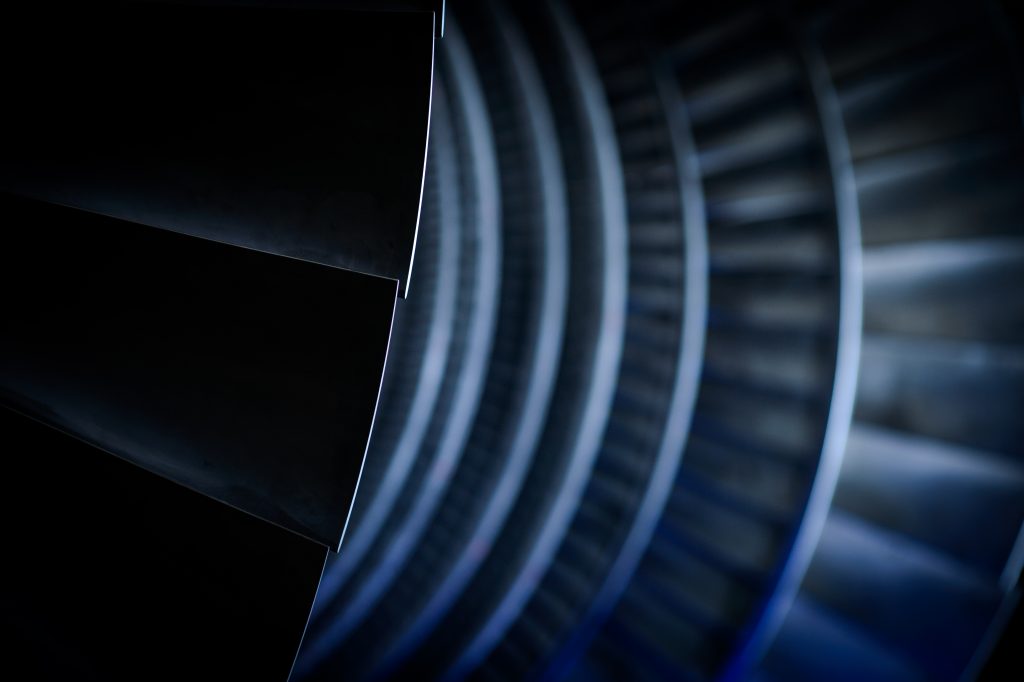

The heart of power generation

At the epicentre of electricity generation is Drax’s six turbines. These heavy-duty pieces of equipment do the major work involved in generating electricity.

High-pressure steam drive the blades which rotates the turbine at 3,000 revolutions per minute (rpm). This in turn spins the generator where energy is converted into the electricity that will eventually make it into our homes.

These are rugged pieces of kit operating in extreme conditions of 165 bar of pressure and temperatures of 565 degrees Celsius. Each of the six turbine shaft lines weighs 300 tonnes and is capable of exporting over 600 megawatts (MW) into the grid.

One of the most important parts of the entire process, turbines are carefully maintained to ensure maximum efficiency. Even a slight percentage increase in performance can translate into millions of pounds in savings.

Turning fuel to fire

To create the steam needed to spin turbines at 3,000 rpm, Drax needs to heat up vast amounts of water quickly and this takes a lot of heat.

The power station’s furnaces swirl with clouds of the burning fuel to heat the boiler. Biomass is injected into the furnace in the form of a finely ground powder. This gives the solid fuel the properties of a gas, enabling it to ignite quickly. Additional air is pumped into the boiler to drive further combustion and optimise the fuel’s performance.

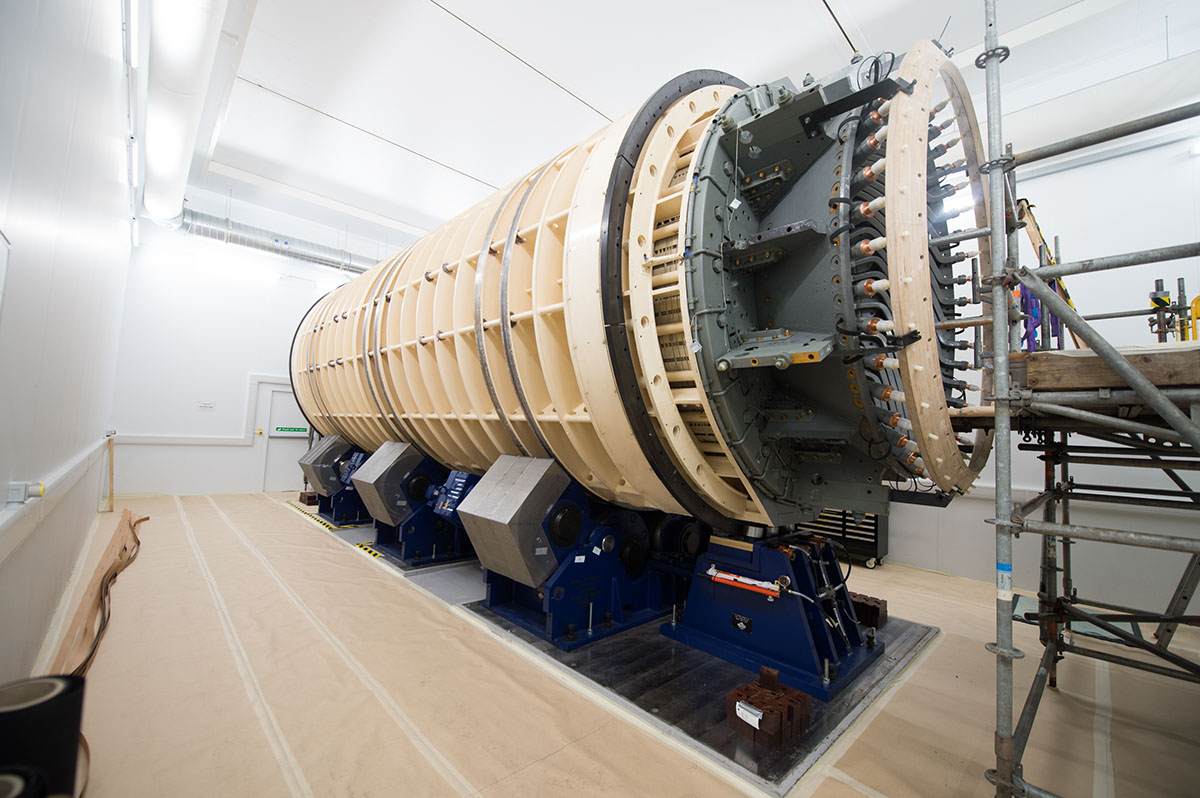

Pulveriser

How do you turn hundreds of tonnes of biomass pellets into a powder every day? That’s the task the pulveriser take on. In each of the power plant’s 60 mills, 10 steel and nickel balls, each weighing 1.2 tonnes, operate in extreme conditions to crush, crunch and pulverise fuel.

These metal balls rotate 37 times a minute at roughly 3 mph, exerting 80 tonnes of pressure, crushing all fuel in their path. Air is then blasted in at 190 degrees Celsius to dry the crushed fuel and blow it into the boiler at a rate of 40 tonnes per hour.

The journey begins: biomass arrives

Biomass arrives at Drax by the train-load. Roughly 14 arrive every day at the power station, delivering up to 20,000 tonnes ready to be used as fuel.

These trains arrive from ports in Liverpool, Tyne, Immingham and Hull and are specially designed to maximise the efficiency of the entire delivery process, allowing a full train to unload in 40 minutes without stopping.

The biomass is then taken to be stored inside Drax’s four huge storage domes. Each capable of fitting the Albert Hall inside, the domes can hold 300,000 tonnes of compressed wood pellets between them.

Here the biomass waits until it’s needed, at which point it makes its way along a conveyor belt to the pulveriser and the process of generating the electricity that powers your breakfast begins.

Homes that power themselves

Homes that power themselves

Bigger, more efficient batteries

Bigger, more efficient batteries