People love to celebrate inventors. It’s inventors that Apple’s famous 90s TV ad claimed ‘Think Different’, and in doing so set about changing the world. The renewable electricity sources we take for granted today all started with such people, who for one reason or another tried something new.

These are the stories of the people behind five sources of renewable electricity, whose inventions and ideas could help power the world towards a zero-carbon future.

The magician’s hydro house

Using rushing rivers as a source of power dates back centuries as a mechanised way of grinding grains for flour. The first reference to a watermill dates from all the way back to the third century BCE.

However, hydropower also played a big role in the early history of electricity generation – the first hydroelectric scheme first came into action in 1878, six years before the invention of the modern steam turbine.

What important device did this early source of emissions-free electricity power? A single lamp in the Northumberland home of Victorian inventor William Armstrong. This wasn’t the only feature that made the house ahead of its time.

Water pressure also helped power a hydraulic lift and a rotating spit in the kitchen, while the house also featured hot and cold running water and an early dishwasher. One contemporary visitor dubbed the house a ‘palace of a modern magician’.

The first commercial hydropower power plant, however, opened on Vulcan Street in Appleton, Wisconsin in 1882 to provide electricity to two local paper mills, as well as the mill owner H.J. Rogers’ home.

After a false start on 27 September, the Vulcan Street Plant kicked into life in earnest on 30 September, generating about 12.5 kilowatts (kW) of electricity. It was very nearly America’s first ever commercial power plant, but was beaten to the accolade by Thomas Edison’s Pearl Street Plant in New York which opened a little less than a month earlier.

The switch to silicon that made solar possible

When the International Space Station is in sunlight, about 60% the electricity its solar arrays generate is used to charge the station’s batteries. The batteries power the station when it is not in the sun.

For much of the 20thcentury solar photovoltaic power generation didn’t appear in many more places than on calculators and satellites. But now with more large-scale and roof-top arrays popping up, solar is expected to generate a significant portion of the world’s future energy.

It’s been a long journey for solar power from its origins back in 1839 when 19-year old aspiring physicist Edmond Becquerel first noticed the photovoltaic effect. The Frenchman found that shining light on an electrode submerged in a conductive solution created an electric current. He did not, however, have any explanation for why this happened.

American inventor Charles Fritts was the first to take solar seriously as a source of large-scale generation. He hoped to compete with Thomas Edison’s coal powered plants in 1883, when he made the first recognisable solar panel using the element selenium. However, they were only about 1% efficient and never deployed at scale.

It would not be until 1953, when scientists Calvin Fuller, Gerald Pearson and Daryl Chapin working at Bell Labs cracked the switch from selenium to silicon, that the modern solar panel was created.

Bell Labs unveiled the breakthrough invention to the world the following year, using it to power a small toy Ferris wheel and a radio transmitter.

Fuller, Pearson and Chapin’s solar panel was only 6% efficient, a big step forward for the time, but today panels can convert more than 40% of the sun’s light into electricity.

The wind pioneers who believed in self-generation

Offshore wind farm near Øresund Bridge between Sweden and Denmark

Like hydropower, wind has long been harnessed as a source of power, with the earliest examples of wind-powered grain mills and hydro pumps appearing in Persia as early as 500 BC.

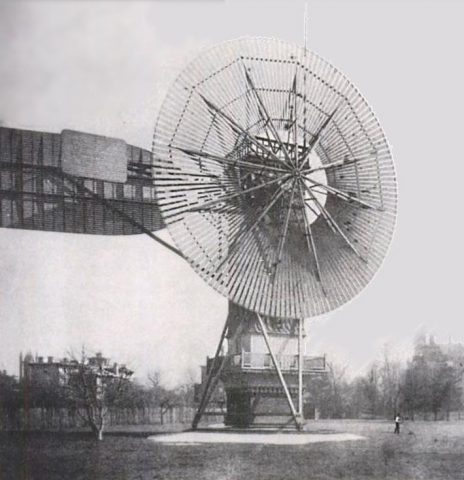

The first electricity-generating windmill was used to power the mansion of Ohio-based inventor Charles Brush. The 60-foot (18.3 metres) wooden tower featured 144 blades and supplied about 12 kW of electricity to the house.

Charles Brush’s wind turbine charged a dozen batteries each with 34 cells.

The turbine was erected in 1888 and powered the house for two decades. Brush wasn’t just a wind power pioneer either, and in the basement of the mansion sat 12 batteries that could be recharged and act as electricity sources.

Small turbines generating between 5 kW and 25 kW were important at the turn of the 19thinto the 20thcentury in the US when they helped bring electricity to remote rural areas. However, over in Denmark, scientist and teacher Poul la Cour had his own, grander vision for wind power.

La Cour’s breakthroughs included using a regulator to maintain a steady stream of power, and discovering that a turbine with fewer blades spinning quickly is more efficient than one with many blades turning slowly.

He was also a strong advocate for what might now be recognised as decentralisation. He believed wind turbines provided an important social purpose in supplying small communities and farms with a cheap, dependable source of electricity, away from corporate influence.

In 2017, Denmark had more than 5.3 gigawatts (GW) of installed wind capacity, accounting for 44% of the country’s power generation.

The prince and the power plant

Larderello, Italy

Italian princes aren’t a regular sight in the history books of renewable energy, but at the turn of the last century, on a Tuscan hillside, Piero Ginori Conti, Prince of Trevignano, set about harnessing natural geysers to generate electricity.

In 1904 he had become head of a boric acid extraction firm founded by his wife’s great-grandfather. His plan for the business included improving the quality of products, increasing production and lowering prices. But to do this he needed a steady stream of cheap electricity.

In 1905 he harnessed the dry steam (which lacks moisture, preventing corrosion of turbine blades) from the geographically active area near Larderello in Southern Tuscany to drive a turbine and power five light bulbs. Encouraged by this, Conti expanded the operation into a prototype power plant capable of powering Larderello’s main industrial plants and residential buildings.

It evolved into the world’s first commercial geothermal power plant in 1913, supplying 250 kW of electricity to villages around the region. By the end of 1943 there was 132 megawatts (MW) of installed capacity in the area, but as the main source of electricity for central Italy’s entire rail network it was bombed heavily in World War Two.

Following reconstruction and expansion the region has grown to reach current capacity of more than 800 MW. Globally, there is now more than 83 GW of installed geothermal capacity.

The engineer who took on an oil crisis with wood

Compressed wood pellet storage domes at Baton Rouge Transit, Drax Biomass’ port facility on the Mississippi River

While sawmills had experimented with waste products as a power sources and compressed sawdust sold as domestic fuel, it wasn’t until the energy crisis of the 1970s that the term biomass was coined and wood pellets became a serious alternative to fossil fuels.

As a response to the 1973 Yom Kippur War, the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) placed oil embargoes against several nations, including the UK and US. The result was a global price increase from $3 in October 1973 to $12 in March 1974, with prices even higher in the US, where the country’s dependence on imported fossil fuels was acutely exposed.

One of the most vulnerable sectors to booms in oil prices was the aviation industry. To tackle the growing scarcity of petroleum-based fuels, Boeing looked to fuel-efficiency engineer Jerry Whitfield. His task was to find an alternative fuel for industries such as manufacturing, which were hit particularly hard by the oil shortage and subsequent recession. This would, in turn, leave more oil for planes.

Wood pellets from Morehouse BioEnergy, a Drax Biomass pellet plant in northern Louisiana, being unloaded at Baton Rouge Transit for storage and onward travel by ship to England.

Whitfield teamed up with Ken Tucker, who – inspired by pelletised animal feed – was experimenting with fuel pellets for industrial furnaces. The pelletisation approach, combined with Whitfield’s knowledge of forced-air furnace technology, opened a market beyond just industrial power sources, and Whitfield eventually left Boeing to focus on domestic heating stoves and pellet production.

One of the lasting effects of the oil crisis was a realisation in many western countries of the need to diversify electricity generation, prompting expansion of renewable sources and experiments with biomass cofiring. Since then biomass pellet technology has built on its legacy as an abundant source of low-carbon, renewable energy, with large-scale pellet production beginning in Sweden in 1992. Production has continued to grow as more countries decarbonise electricity generation and move away from fossil fuels.

Since those original pioneers first harnessed earth’s renewable sources for electricity generation, the cost of doing so has dropped dramatically and efficiency skyrocketed. The challenge now is in implementing the capacity and technology to build a safe, stable and low-carbon electricity system.