This crisis will be remembered for many things. Many are not positive, but some are inspiring. Around the world we’ve seen tremendous acts of kindness and witnessed remarkable resilience from people continuing to live, work and to support one another. The actions we are all taking as individuals, businesses and communities will not only help us get through this crisis, they will shape how we emerge from it.

At Drax we are proud of the ongoing role we’re playing in supporting the UK and its essential services, continuing to generate and supply the electricity needed to keep people healthy and the economy running.

It is what we have always done, and it is what we will continue to do.

This is possible because our people have continued to carry out their important work in these uncertain times safely and responsibly. My leadership team in the UK and US must continue to support them, and we must also support the communities they are a part of.

Employees Drax Power Station show their support and appreciation for the heroic efforts of those within the NHS by turning one of its cooling towers blue at 8pm each Thursday

Our communities are at the core of what we do and who we are. They support our business globally and enable us to supply energy to the country. We have a responsibility to do what we can to help them through this crisis.

To do this we have put together a Covid-19 support package totalling more than three quarters of a million pounds that goes beyond just financing to make a positive impact. I’d like to highlight a few of these.

Supporting communities in Great Britain and the US

The Robinson family collect their laptop at Selby Community Primary School

The closures of schools and the need to turn homes into classrooms has been one of the biggest changes for many families. With children now depending on technology and the internet for schooling, there’s a very real chance those without access may fall behind, with a long term negative impact on their education.

We want to ensure no child is left out. So, we have donated £250,000 to buy 853 new laptops, each with three months of pre-paid internet access, and delivered them to schools and colleges local to our sites across the UK.

This has been implemented by Drax, working closely with headteachers. As one of our local heads Ian Clennan told us: “Schools don’t just provide education – they’re a whole support system. Having computers and internet access means pupils can keep in touch with their teachers and classmates more easily too – which is also incredibly important at the moment.”

In the US, we’re donating $30,000 to support hardship funds for the communities where we operate. Our colleagues in Louisiana are playing an active role in the community, and in Amite County, Mississippi, they have helped provide PPE to first responders as well as supporting charities for the families worse affected.

Helping businesses, starting with the most vulnerable

As an energy supplier to small and medium sized businesses (SMEs), we must act with compassion and be ready to help those who are most economically exposed to the crisis. To do this, we are launching a number of initiatives to support businesses, starting with some of the most vulnerable.

It’s clear that care homes require extra support at this time. We are offering energy bill relief for more than 170 small care homes situated near our UK operations for the next two months, allowing them to divert funds to their other priorities such as PPE, food or carer accommodation.

It’s clear that care homes require extra support at this time. We are offering energy bill relief for more than 170 small care homes situated near our UK operations for the next two months, allowing them to divert funds to their other priorities such as PPE, food or carer accommodation.

But it is also important we understand how difficult a period this is for small businesses of all kinds. Many of our customers are facing financial pressure that was impossible to forecast. To help relieve this, we have agreed deferred payment plans with some of our customers who are unable to pay in full. We have also extended current energy prices for three months for 4,000 customers of Opus Energy who have not been able to secure a new contract during this period.

The impact of this crisis will be long term, so we made a significant, two-year charitable donation to Business Debtline. A dedicated phoneline and webpage will be provided to our small businesses customers, offering free debt advice and helping them to recover for the future.

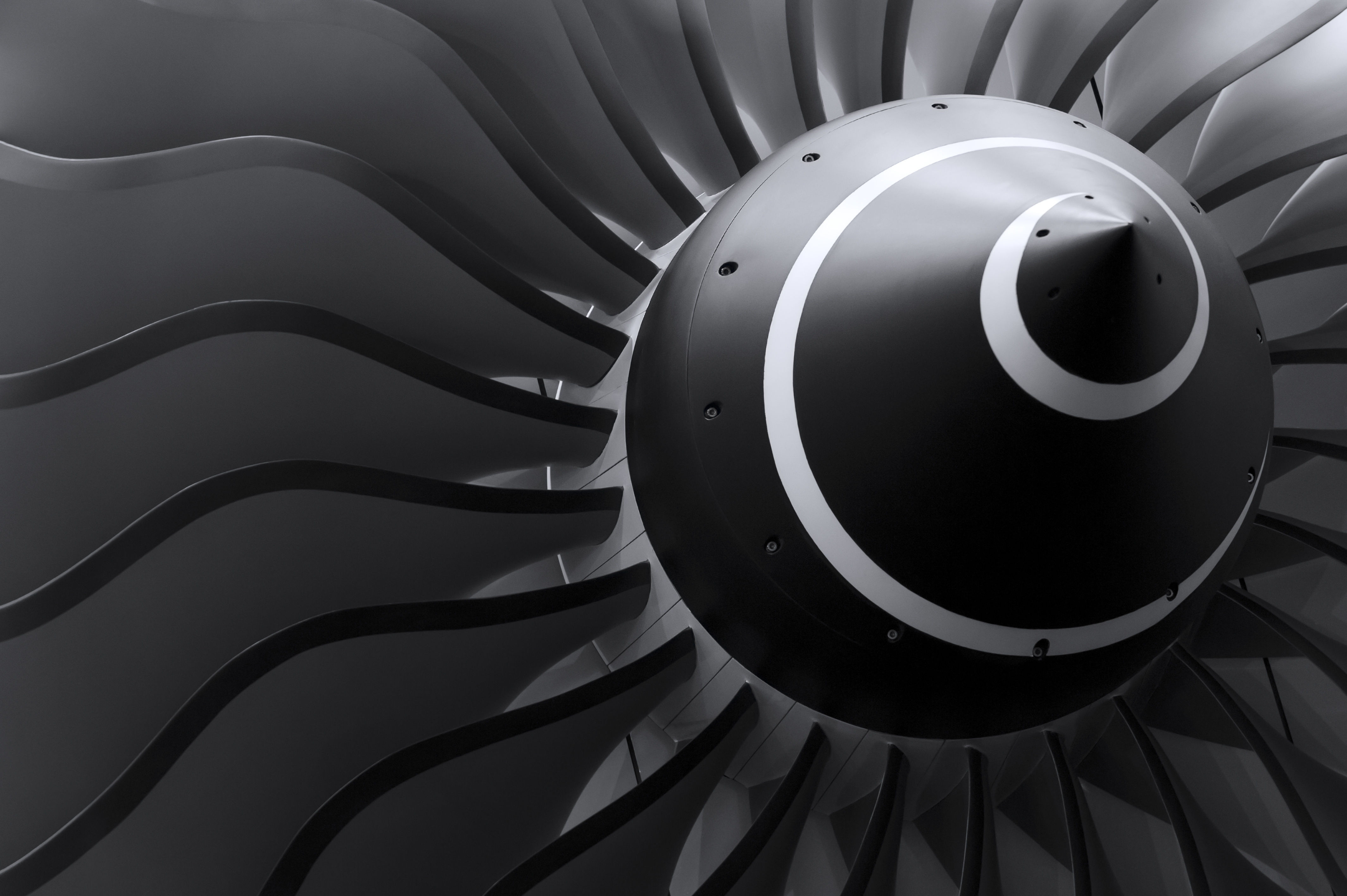

An engineer looks up at flue gas desulphurisation unit (FGD) at Drax Power Station. The massive pipe would transport flue gas from the Drax boilers to the carbon capture and storage (CCS) plant for CO2 removal of between 90-95%.

Change for the future recovery

While there is still uncertainty around how the UK, the US and the world will emerge from the pandemic it is the responsibility of the whole energy industry to show compassion for its customers and to take the actions needed to soften the economic blow that Covid-19 is having across the globe.

The disruption to normal life caused by the pandemic has changed how the country uses electricity overnight. In the coming weeks we will be publishing a more in-depth view from Electric Insights showing exactly what effect this has had and what it might reveal for the future of energy.

No matter what that future holds, however, we will remain committed to enabling a zero carbon, lower cost energy future. This will mean not only supporting our people, our communities and our countries through the coronavirus crisis, but striving for a bright and optimistic future beyond it. A future where people’s immediate health, safety and economic wellbeing are prioritised alongside solutions to another crisis – that of climate change.

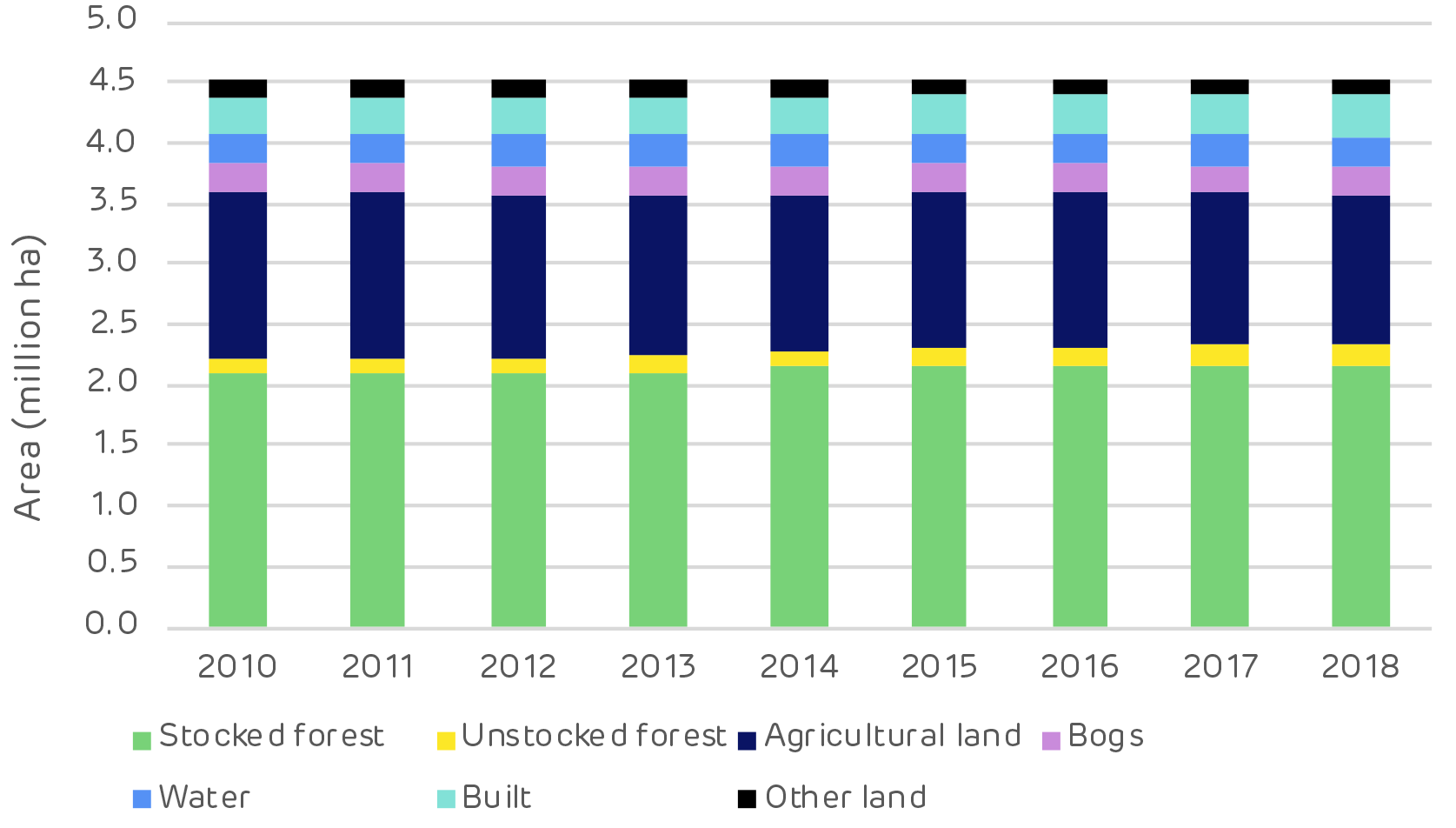

![Reforestation in Estonia. * Note: Since 2014 it has not been compulsory for private and other forest owners to submit reforestation data. [Click to view/download]](https://www.drax.com/uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/8/2020/03/figure_3.13-1024x590.png)

![Species mix in Estonian forests [Click to view/download]](https://www.drax.com/uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/8/2020/03/figure_3.3.png)

![Comparison of sawlog and pulpwood prices [click to view/download]](https://www.drax.com/uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/8/2020/03/Picture-1.pdf2_-1.png)

Aeroplanes still rely on fossil fuels to provide the huge amount of power needed for take-off. Globally flights produced

Aeroplanes still rely on fossil fuels to provide the huge amount of power needed for take-off. Globally flights produced