‘Terroir’ comes from the French word ‘terre’, meaning land, earth or soil. In the French wine industry, it refers to the land from which grapes are grown. It is believed the terroir gives the grapes a unique quality specific to that particular growing site.

Terroir dictates the type of wine that comes from a region – it’s the reason we call one bottle a Bordeaux, and another a Côtes Du Rhone.

But could the idea of terroir hold relevance beyond just wine? What if we looked at electricity in the same way?

Certain environments are better placed to produce certain types of electricity.

These are some of the regions making the most of their unique location and landscape to produce electricity that makes sense for them.

La Rance tidal barrage

Brittany, France

Brittany boasts one third of mainland France’s coasts, and has long been a top destination for surfers, with waves as high as 7.6 metres in some places. With such tempestuous waters, it’s the perfect location for La Rance Tidal Power Station –the world’s first station of its kind. Opened in 1966, the site was chosen because it has the highest tidal range in France.

Tidal barrages like La Rance harness the potential energy in the difference in height between low and high tides.

The barrage creates an artificial reservoir to enable different water levels, which then drives turbines and generators to produce electricity.

While the station has been operating for close to 50 years, old tidal mills are still dotted around the Rance river, some dating back to the 15th century – proof that tidal power has deep roots in this region.

Xinjiang, China

Whilst China may have some of the world’s most polluted cities, it is also the world’s biggest producer of renewable energy – including wind power. With one of the largest land masses on the planet, one in every three of the world’s wind turbines is in China, with the government installing one per hour in 2016.

In places like Xinjiang, China’s most westerly province, the windy weather used to be a nuisance, with overturned lorries and de-railed trains being a regular sight. This is caused by mountain ranges between Dabancheng and Ürümqi which form a natural wind tunnel, increasing the wind speed as air passes through. These days the region is harnessing this same wind to produce incredible amounts of electricity – with 27.8 terwatt hours (TWh) of electricity coming from the region in the first nine months of 2018.

Onshore wind farm in Xinjiang

Xinjiang local Wu Gang founded Goldwind to build China’s first windfarm here in the 1980s. Today it’s the world’s second largest turbine maker. The turbines work on a simple premise: wind turns the turbine blades which are connected to a rotor, causing it to spin. This in turn is connected to a generator, which takes the wind’s kinetic energy to produce electricity.

Hengill, Iceland

Iceland sits where the North American and Eurasian tectonic plates meet, meaning that magma rises close to the surface, bringing with it a lot of energy potential. One example of how the Icelandic people are harnessing this power is The Hellisheiði, the second largest geothermal power station in the world.

Here, high-pressure geothermal steam is extracted from 30 wells, ranging from 2,000 to 3,000 metres deep, and is used to turn turbines and generate electricity. This renewable plant has a capacity of 303 megawatts (MW) of electricity, which is used to power the capital city of Reykjavik.

The site was chosen due to its location in the Hengill volcanic area in the south of Iceland, one of the most active geothermal areas on the planet. Here, a giant magma chamber sits underground, with thousands of hot springs above. According to Iceland’s National Energy Authority, geothermal power from sites like this accounts for 25% of the country’s electricity production and 66% of primary energy usage.

But Icelanders aren’t only using the geothermal landscape for energy production – chefs here can cook food simply by burying it in the ground, producing delicacies like rúgbrauð, which translates as ‘hot spring bread’.

Ouarzazate, Morocco

From Iceland’s below-zero temperatures to Morocco, a popular holiday destination for sun-seekers, with 330 days of sunshine a year. Morocco lays claim to a chunk of the Sahara Desert, famously known as one of the hottest climates in the world. Where better, then, to situate the world’s largest solar thermal power plant?

Noor solar thermal plant

The Moroccan city of Ouarzazate, nicknamed the ‘door of the desert’ plays host to the huge Noor Complex, which is still under construction and is being implemented in four parts. The latest piece of the puzzle is Noor III, which was hooked up to Morocco’s electricity grid last year. Here, 7,400 mirrors reflect sun rays onto Noor III’s tower, the highest solar-thermal tower in the world, concentrating at the top of the building to create around 500ºC of heat. This heats up the molten salts inside the tower, which travel through a series of pipes, creating high pressure steam. This steam then moves a turbine to generate electricity.

Molten salts are used at Noor III because they can operate at high temperatures and store heat effectively, so that the site can continue to produce energy for up to 7.5 hours when there’s no sun. Once up and running, the plant will generate enough energy to power 120,000 homes with no atmospheric emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2). Along with the other projects at the Noor Complex, Noor III is helping Morocco to achieve its goal of obtaining 42% of its power from renewable sources by 2020.

Ben Cruachan, Scotland

The sun rays that shine on the Noor Complex are few and far between in the Highlands, but there are mountains a-plenty – Ben Cruachan being one of them. Ben Cruachan is the highest point in the Argyll and Bute area of Scotland and is right next to the picturesque Loch Awe. This provides the backdrop for the world’s first high head reversible pumped-storage hydro scheme, built by British engineer Edward McColl over 50 years ago.

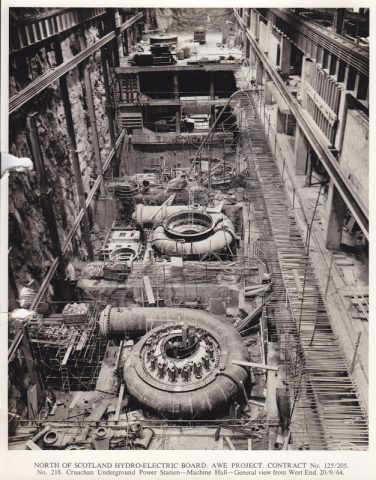

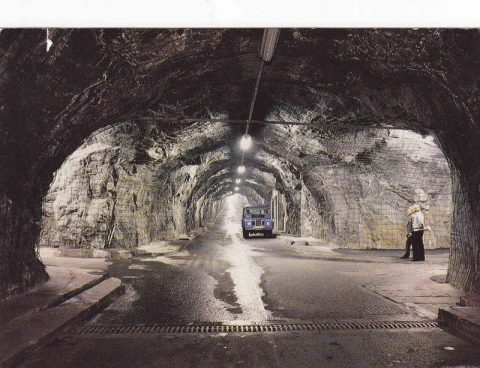

With the help of a 4,000-strong army of workers nicknamed the Tunnel Tigers, McColl turned the slopes of Ben Cruachan into a geological battery which Great Britain still relies on today.

It works by using excess electricity on the national grid to pump water from Loch Awe at the foot of the mountain up to the Cruachan Reservoir 300 metres above. During times of heightened demand – like when everyone puts the kettle on during a Coronation Street ad break or when the wind speed suddenly drops around breakfast time – this water is released back down the mountain to turn the turbines that live inside the hollowed mountain.

In this way, Cruachan Power Station can meet the nation’s energy needs within seconds, whereas gas or nuclear stations would take many tens of minutes or hours to reach such capacity.

While Ben Cruachan lends itself perfectly to this pumped-storage hydro facility, it is only one of four such sites in the UK. The challenge in installing more is that there are only a few sites which are mountainous with suitably large bodies of water nearby – things that are inherently necessary for pumped-storage hydroelectricity.

The growing importance of ‘terroir’

All of these places embrace the land around them to produce energy in inventive ways, and as levels of decarbonisation grow around the world, there are an increasing number of places using what’s available close to home for energy solutions.

Take Barbados, a country that has traditionally relied on imported fossil fuels for 96% of its electricity. But with short driving distances and 220 days of pure sunlight every year, the government has seen the potential for electric vehicles run by solar power. With modular solar carports now a regular sight in Barbados, the island has become one of the world’s top users of EVs – preserving the picturesque landscape and reducing its dependence on imported petrol.

Solar panels above an office car park in Barbados

Meanwhile Palau, a small Pacific island nation, is building the world’s largest microgrid, consisting of 35 MW of solar panels and 45 MWh of energy storage. For a nation threatened by rising sea levels, making use of its geographic features allows it to work towards its 70% renewable energy target by 2050 and reduce its reliance on imports.

As more countries continue to move away from fossil fuels, taking advantage of their unique ‘terroir’ will increasingly enable them to produce electricity that works with their landscape.

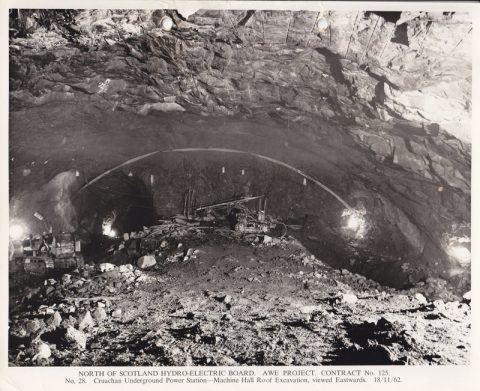

The access tunnel, cavern and the networks of passageways and chambers that make up the power station were all blasted and drilled by a workforce of 1,300 men in the

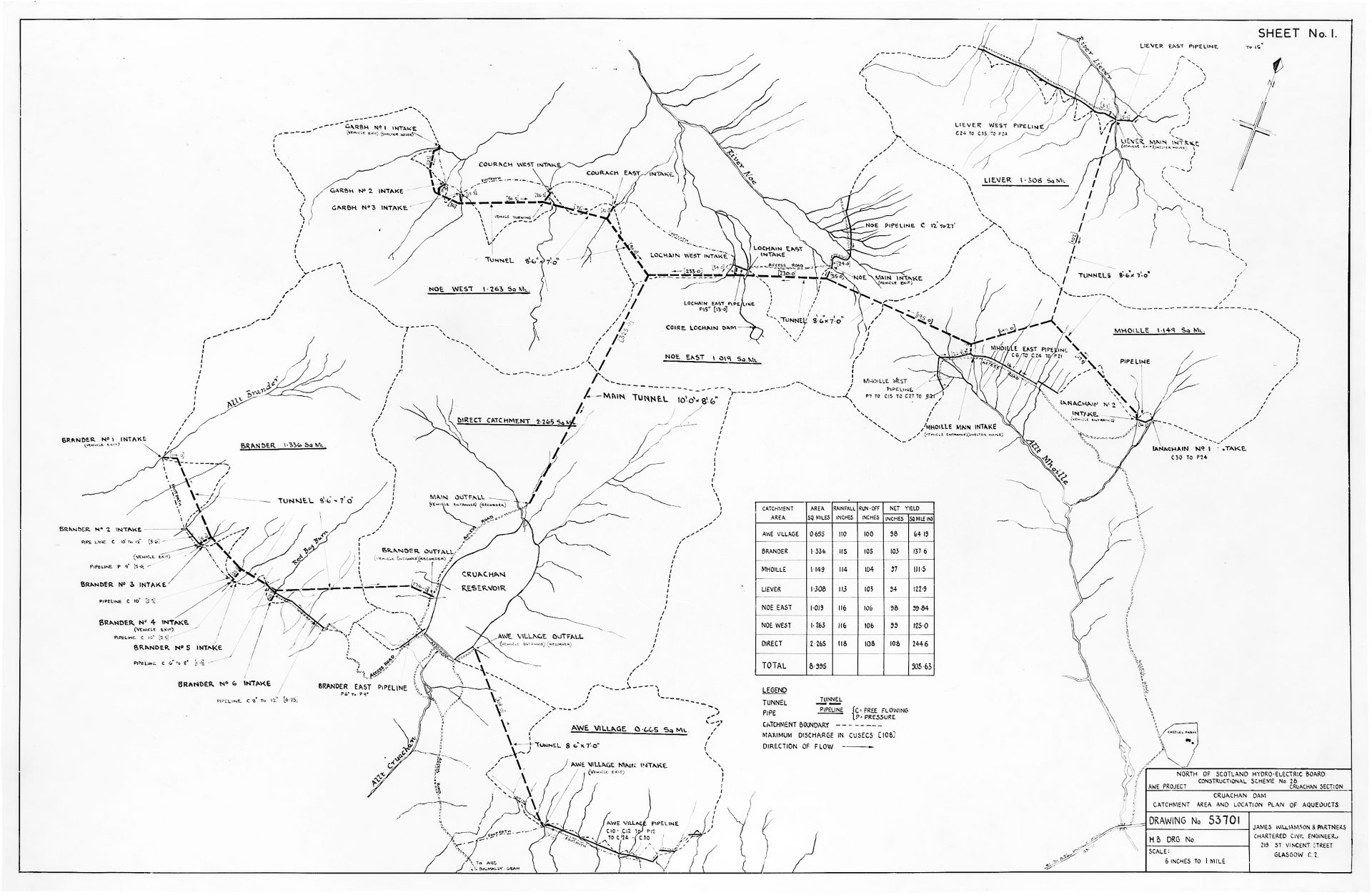

The access tunnel, cavern and the networks of passageways and chambers that make up the power station were all blasted and drilled by a workforce of 1,300 men in the  However, the reservoir also makes use of the aqueduct system made up of 19 kilometres of tunnels and pipes that covers 23 square kilometres of the surrounding landscape, diverting rainwater and streams into the reservoir. Calculating quite how much of the reservoir’s water comes from the surrounding area is difficult but estimates put it at around a quarter.

However, the reservoir also makes use of the aqueduct system made up of 19 kilometres of tunnels and pipes that covers 23 square kilometres of the surrounding landscape, diverting rainwater and streams into the reservoir. Calculating quite how much of the reservoir’s water comes from the surrounding area is difficult but estimates put it at around a quarter.