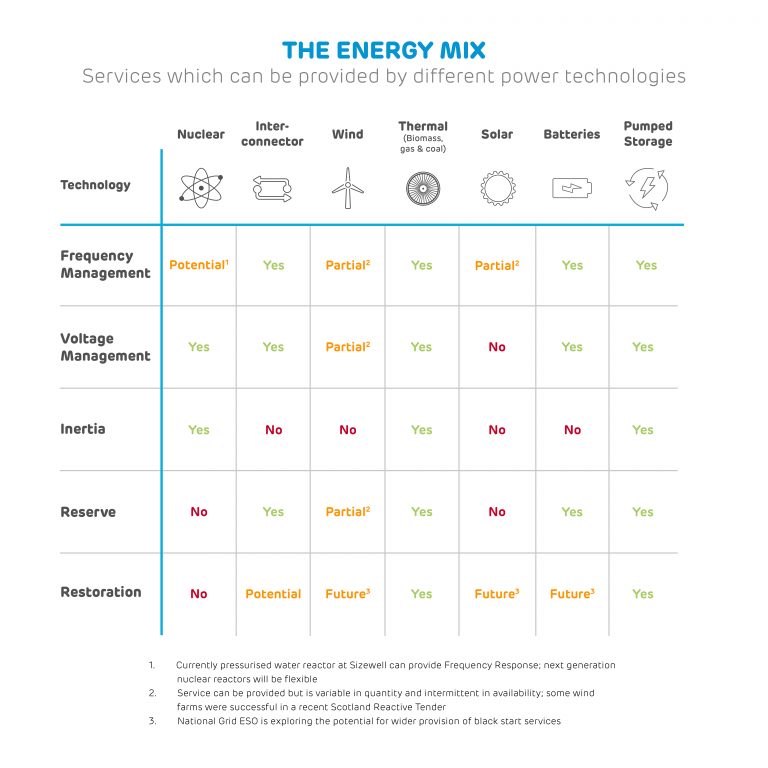

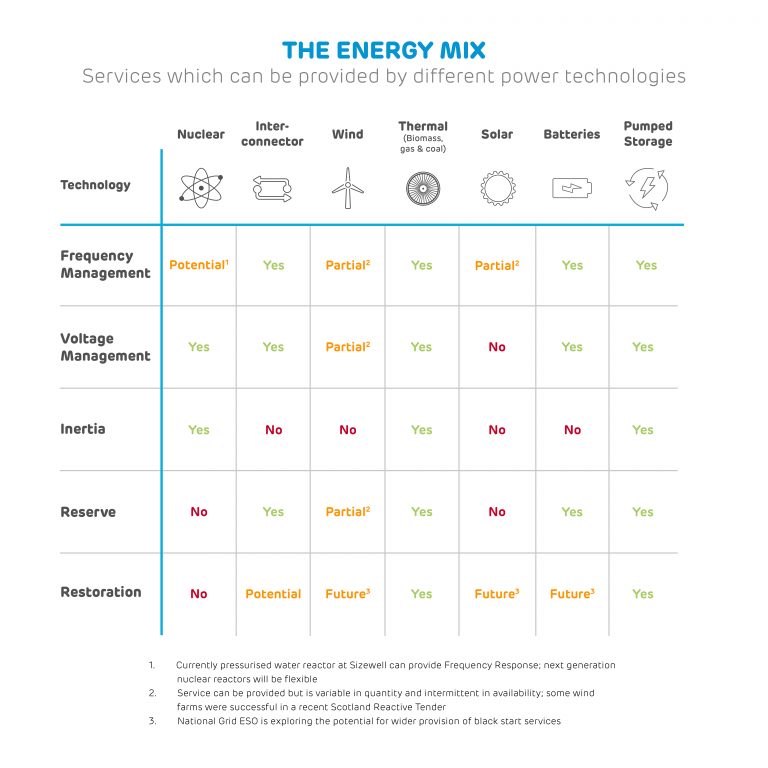

Great Britain’s electricity system is in the middle of a revolution. Where power supply was once dominated by some big thermal coal, gas and nuclear power stations, it now comes from an array of sources. Thousands of new individual points have been added to the mix, ranging from large interconnectors, that bring in power from neighbouring countries, through to wind farms, solar panels, small gas and diesel engines.

The energy mix has been changing radically, with low carbon sources expected to provide 58% of Great Britain’s power by 2020, up from 22% in 2010 and 53% in 2018. However, the security standards at which the electricity grid needs to be operated remain the same; these are predominantly voltage and frequency, and nominally 230 V and 50Hz for a domestic consumer.

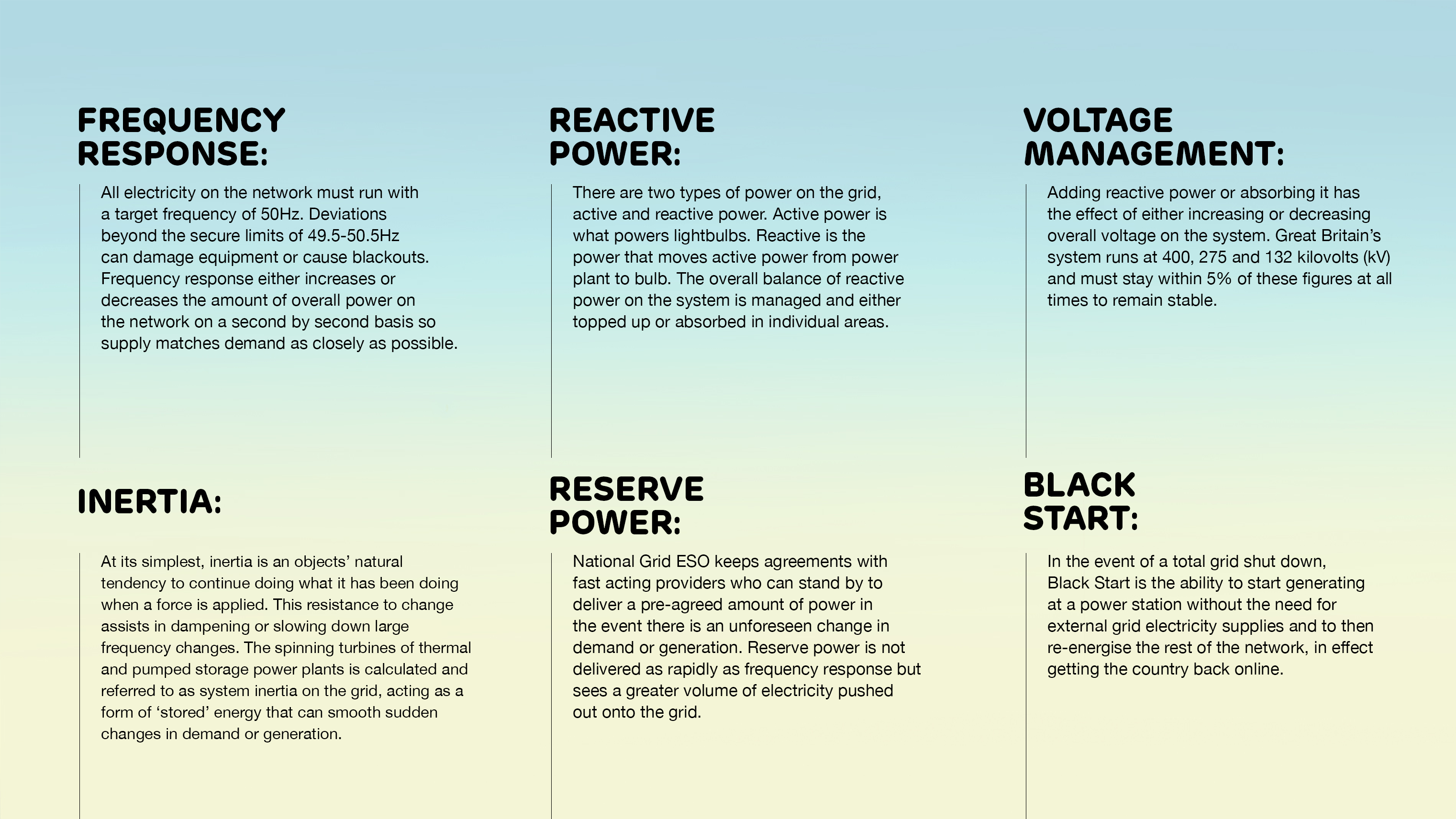

The operation of the Transmission system, including maintaining these standards is overseen by the National Grid Electricity System Operator (ESO), using a set of vital tools it needs to have available, known as ancillary services. Some of this capability was inherent in large generators, which could provide the ancillary services required to keep a stable transmission system. Maintaining system stability, with thousands of generation points — a large part of which are not directly controllable — is increasingly challenging.

Click graphic to view/download

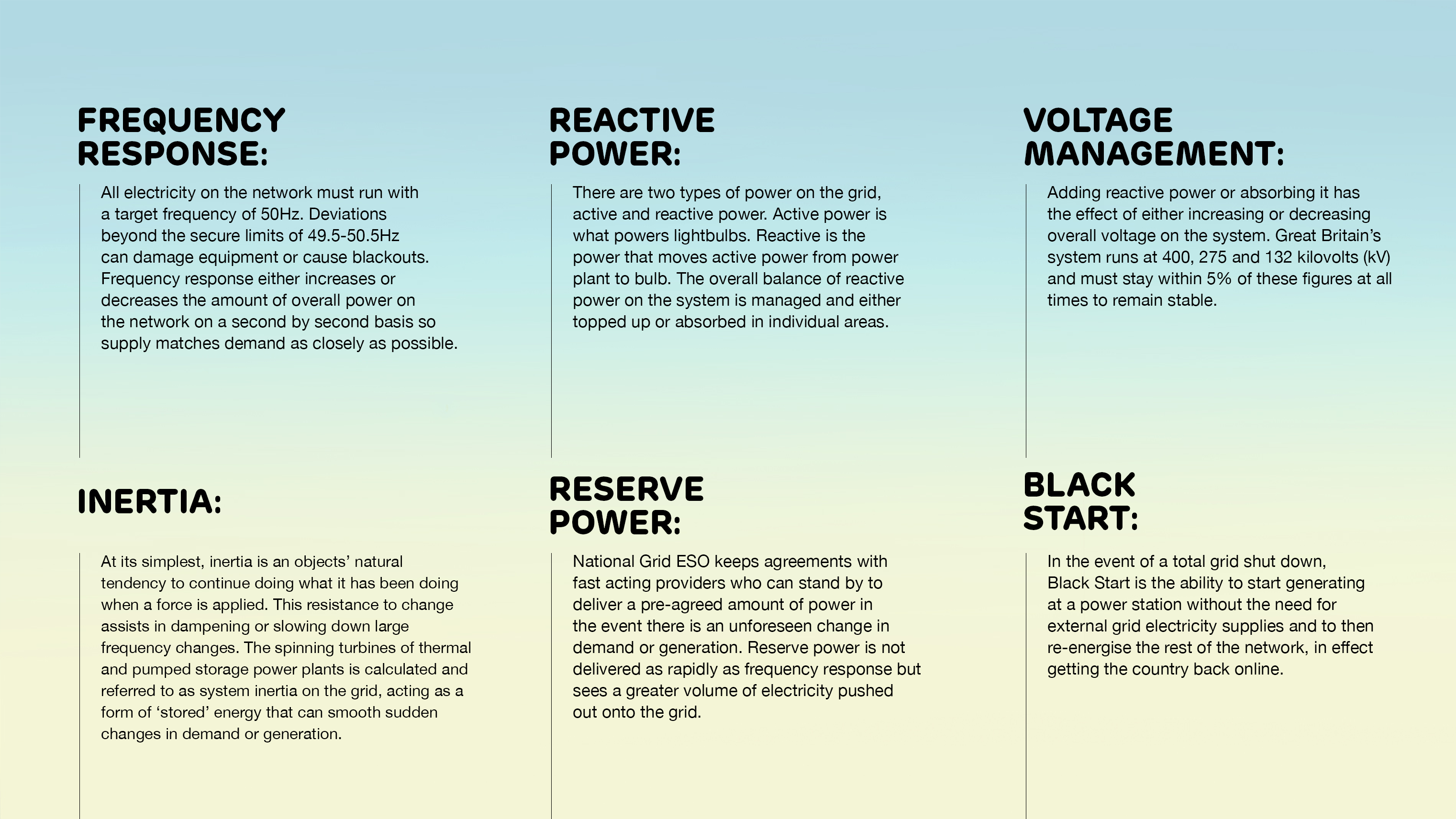

Ancillary services enable electricity to reach the end customer when and where it is required, in a safe manner, within acceptable quality standards. In addition to managing voltage and frequency levels, these standards also include maintaining adequate reserves to accommodate demand forecast uncertainties, generator breakdown and system faults. 1.

As the electricity mix changes, so must the process by which these services are secured. A diverse set of existing and genuinely new solutions will be needed to keep the lights on in the net zero carbon future.

Three steps to creating the right environment for a stable, resilient future grid:

1. Make the value of ancillary services transparent

In order for companies to help the ESO, be they generators or other service providers, it must be open and transparent about what’s needed to maintain grid stability and build resilience for the future.

“The ESO is the only buyer in the ancillary services market and is well-positioned to understand how the system is evolving. It should be proactively flagging how its needs may evolve in the future, so that the market can develop solutions to meet them”, says Marcelo Torres, Drax’s Regulation Manager – Markets.

Certain ancillary services still don’t have their own competitive markets and are provided as a “by-product” of the generation of electricity. An example is reactive power, for which there are no developed functioning regional markets yet. Generally, all power stations connected to the transmission network with a generation capacity of over 50MW are required to have the capability to provide this service, at a default price that may not reflect its real value to the system.

Another example is inertia, provided today largely through the heavy spinning turbines of thermal and pumped-storage hydro stations, which serve as stored energy that can slow down or smooth out sudden changes in network frequency.

If ancillary services were valued explicitly, market participants would have an insight into how much they are actually worth to the ESO and the grid’s stability, which would in turn incentivise new, competitive products to reach the market.

Torres points to technologies such as synchronous compensators, which are machines capable of providing ancillary services, including inertia and reactive power, without generating potentially unneeded electricity.

Click graphic to view/download

“These solutions will enable more renewables to connect safely to the network at a lower cost to consumers. For these solutions to come forward, ascribing the right value to ancillary services will be key. Without clear price signals, there is a risk of underinvestment in those technologies that provide the services needed, potentially resulting in price shocks for consumers”.

“The ESO is moving in the right direction with its recent Network Development Pathfinder projects. It has accelerated this work, launching its first ever tender for inertia and should roll out similar initiatives GB-wide. Such procurements should align with existing investment signals such as those provided by the Capacity Market. This should allow for the right type of capacity to be built where it is most needed, delivering a secure and resilient grid”.

2. Create market confidence

“Constructing the machinery and infrastructure that will enable the ESO to operate a carbon-free system will require major financial investment, as well as years to plan and build,” says Torres.

“This can only be achieved if Ofgem designs the ESO’s incentives in a way that rewards it for taking bold, strategic initiatives that have the potential to deliver good value for money to consumers in the long-term.”

Evidence of this working is shown in the success of offshore wind, which now provide around a sixth of Great Britain’s electricity, at record low prices. This is partly due to the government providing offshore wind developers with revenue stabilisation mechanisms, known as ‘Contracts for Difference’ (CfDs).

This is not a new concept for government and regulators around the world looking to enable investment in energy infrastructure. Financing renewables to achieve decarbonisation is enabled through CfDs or market-led hedging tools, like Power Purchase Agreements. Investment to ensure there is sufficient capacity to meet peak demand is secured through long-term contracts, competitively awarded through the Capacity Market. Similarly, investment in interconnection is supported through Ofgem’s ‘Cap & Floor’ regime.

“Subsidy isn’t required for investment in ancillary services. What’s needed,” says Torres, “is a clear and stable market framework designed around the system’s needs, which provides a mix of short and long-term signals. More certainty over the market landscape and the expected returns will lower the risk of these investments and get the solutions needed at a lower overall cost to consumers.”

“Long-term procurement is not the right answer everywhere. Where there is already a mature and liquid market, such as the case for frequency response, buying services closer to real time makes sense for two reasons. First, it allows prices to reflect more accurately the market conditions and therefore the real value of a service at the time when it is needed. Second, it allows a wider range of resources to participate in the market, increasing competition. Striking the right balance between short and long-term procurement is key to create a sustainable ancillary services market.”

Currently, the ESO requests that electricity-generation firms commit to supplying a certain amount of power for the purpose of frequency response, a month ahead of time. For resources such as wind farms or solar, which are dependent on the weather, this makes it extremely difficult for them to enter this market. Even for conventional large thermal generators it can be a problem, as many of them do not know how or if they will be running beyond a few days.

“The ESO is currently conducting some trials procuring frequency response one week in advance. While this is an improvement, it is still too long a lead time for intermittent sources or demand-side response, which ideally need day-ahead or almost real time auctions to unlock their full potential,” says Torres.

“The ancillary services market has been through a prolonged period of change since the ESO published its System Needs and Product Strategy in 2017. Without knowing how the market landscape will look like by the end of these reforms, it’s difficult for providers to develop the right solutions.”

A shift in thinking, which considers what the electricity network might require in the future, and how to provide the market with financial incentives to make it a reality, is needed. A resilient, stable future system is to the advantage of consumers.

3. Diversify

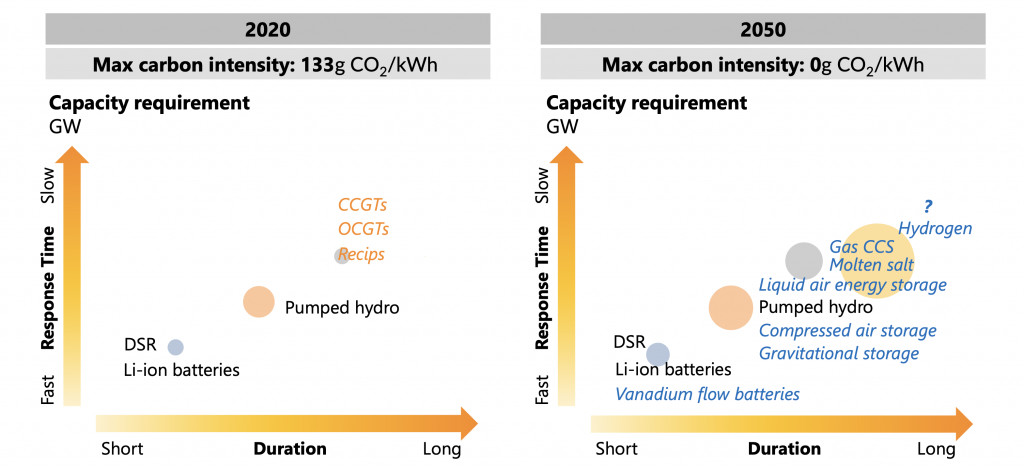

There will be no silver bullet that can solve all the challenges the energy transition poses. Maintaining system reliability in a high renewables world will require large amounts of dispatchable power, with different response time and duration. From small batteries and demand-side response that will manage instantaneously frequency fluctuations, through to large pumped storage hydro plants that will provide backup power during the days when the wind won’t blow and the sun won’t shine. A framework structured around the system’s different needs should aim at harnessing flexibility across a range of technologies and sizes.

Truly diversifying will also involve unlocking the flexibility potential on the distribution grid. To achieve this, the way that access to the distribution network is managed and paid for will need to evolve. Today, with big parts of the distribution network being congested, small flexible assets are asked to wait in the queue for several years or face disproportionate amount of network reinforcement costs to get connected.

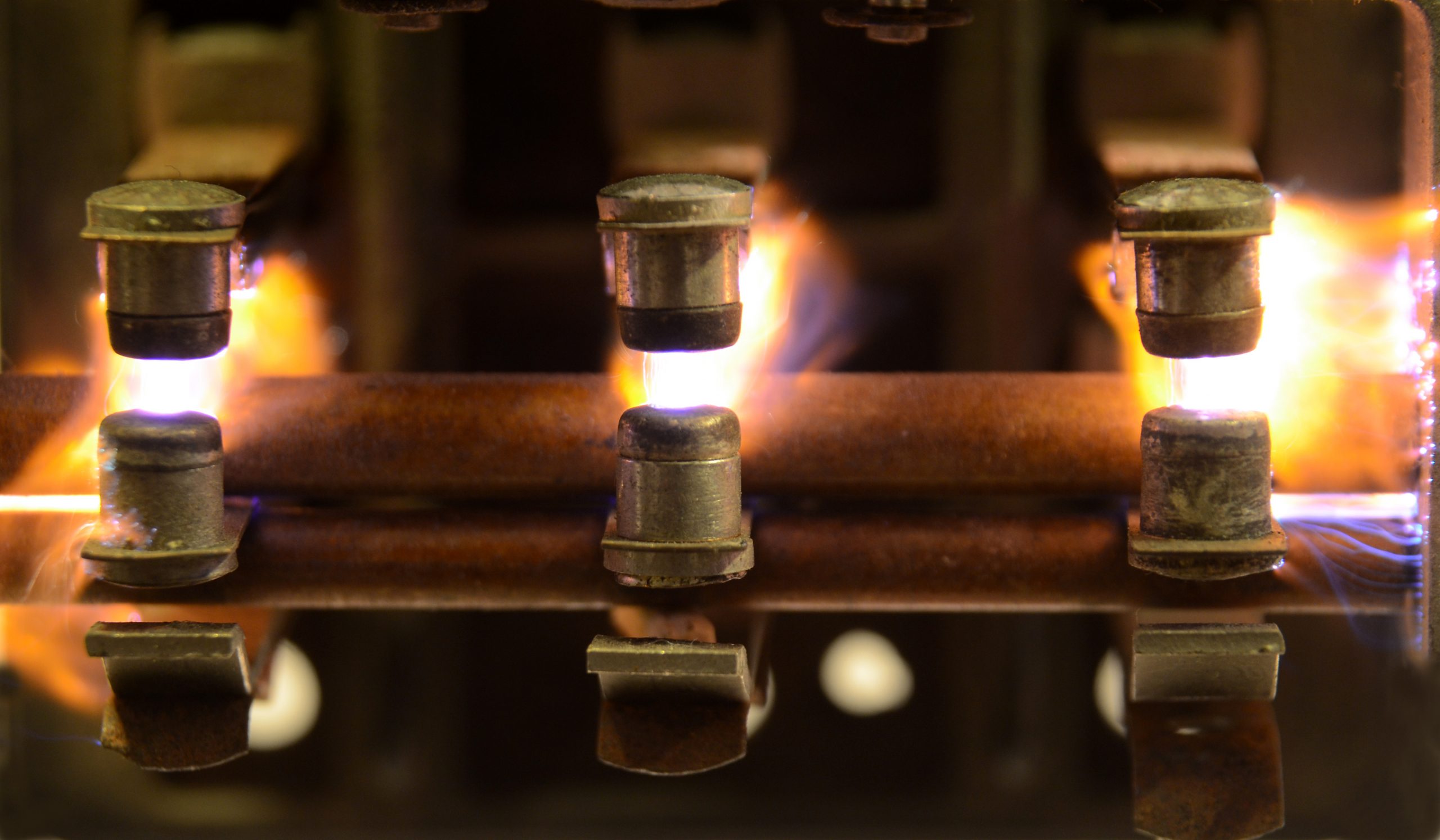

Machine hall, Cruachan Power Station

The ongoing review of the network access and forward-looking charging arrangements needs to address these barriers soon, if we are serious about making use of flexibility to foster the energy transition, while keeping consumer bills as low as possible.

Since 2018, GB’s Distribution Network Operators (DNOs) have been tendering and procuring for various flexibility services to manage congestion in regional electricity grids. In 2019, they published a roadmap setting out the steps they intend to take to enable a smarter and more flexible energy system.

“As we transition from DNOs towards Distribution System Operation – a wider set of functions and services to run a smart distribution grid – the regional networks will be open to market-based flexibility solutions. DSOs will be able to compete on a level playing field, offering options for network reinforcement. As DNOs move from trials to more structured flexibility procurement, harmonisation and effective coordination with the national markets will be the key pre-requisites to reveal the true value that flexibility can bring to the energy system,” argues Torres.

“To build a modern and resilient grid we will need a wider lens on what’s possible. It’s going to be an exciting journey on the road to net zero!”

Chile was an early proponent of energy sharing with its hydrogen programme. The country uses solar electricity generated in the Atacama Desert (which sees 3,000 hours of sunlight a year), to power hydrogen production in a process called electrolysis, which uses electricity to split water into oxygen and hydrogen.

Chile was an early proponent of energy sharing with its hydrogen programme. The country uses solar electricity generated in the Atacama Desert (which sees 3,000 hours of sunlight a year), to power hydrogen production in a process called electrolysis, which uses electricity to split water into oxygen and hydrogen.