How low carbon can Britain’s electricity go? As low as zero carbon still seems a long way off but every year records continue to be broken for all types of renewable electricity. 2018 was no different.

Over the full 12-month period, 53% of all Britain’s electricity was produced from low carbon sources, which includes both renewable and nuclear generation, up from 50% in 2017. The increase in low carbon shoved fossil fuel generation down to just 47% of the country’s overall mix.

The findings come from Electric Insights, a quarterly report commissioned by Drax and written by researchers from Imperial College London.

The report found electricity’s average carbon intensity fell 8% to 217 grams of carbon dioxide per kilowatt-hour of electricity generated (g/kWh), and while this continues an ongoing decline that keeps the country on track to meet the Committee on Climate Change’s target of 100 g/kWh by 2030, it was, however, the slowest rate of decline since 2013.

It also highlights that while Britain can continue to decarbonise in 2019, the challenges of the years ahead will make it tougher to continue to break the records it has over the past few years.

The highs and lows of 2018

Last year, every type of renewable record that could be broken, was broken. Wind, solar and biomass all set new 10-year highs for respective annual, monthly and daily generation, as well as records for instantaneous output (generation over a half-hour period) and share of the electricity mix. The result was a new instantaneous generation high of 21 gigawatts (GW) for renewables, 58% of total output.

Wind had a particularly good year of renewable record-setting. It broke the 15 GW barrier for instantaneous output for the first time and accounted for 48% of total generation during a half hour period at 5am on 18 December.

Overall low carbon generation, which takes into account renewables and nuclear (both that generated in Britain and imported from French reactors), had an equally record-breaking year with an average of almost 18 GW across the full year and a new record for instantaneous output of 30 GW at 1pm on 14 June – nearly 90% of total generation over the half hour period.

While low carbon and individual renewable electricity sources hit record highs, there were also some milestone lows. Coal accounted for an average of just 5% of electricity output over the year, hitting a record low in June, when it made up just 1% of that month’s total generation. Fossil fuel output overall had a similarly significant decline, hitting a decade-low of 15 GW on average for 2018 – 44% of total generation over the year.

One fossil fuel that bucked the trend, however, was gas, which hit an all-time output of 27 GW for instantaneous generation on the night of 26 January. There was low wind on that day last year, plus much of the nuclear fleet was out of action for reactor maintenance. In one case, with seaweed clogging a cooling system.

This was all aided by an ongoing decline in overall demand as ever smarter and more efficient devices helped the country reach the decade’s lowest annual average demand of 33.5 GW. More impressive when considering how much the country’s electricity system has changed over the last decade, however, is the record low demand net of wind and solar. Only 9.9 GW was needed from other energy technologies at 4am on 14 June.

How the generation mix has changed

The most remarkable change in Britain’s electricity mix has been how far out of favour coal has fallen. From its position as the primary source from 2012 to 2014, in the space of four years it has crashed down to sixth in the mix with nuclear, wind, imports, biomass and gas all playing bigger roles in the system.

This sudden decline in 2015 was the result of the carbon price nearly doubling from £9.54 to £18.08 per tonne of carbon dioxide (CO2) in April, making profitable coal power stations loss-making overnight. With coal continuing to crash out of the mix, biomass has become the most-used solid fuel in Britain’s electricity system.

Interconnectors are also playing a more significant part in Britain’s electricity mix since their introduction to the capacity market in 2015. Thanks to increased interconnection to Europe, Britain is now a net importer of electricity, with 22 TWh brought in from Europe in 2018 – nine times more than it exported.

While more of Britain’s electricity comes from underwater power lines, less of it is being generated by water itself. Hydro’s decline from the fifth largest source of electricity to the eighth is the most noticeable shift outside coal’s slide. New large-scale hydro installations are expensive and a secondary focus for the government compared with cheaper renewables.

Hydro’s role in the electricity mix is also affected by drier, hotter summers, which means lower water levels. For solar, by contrast, the warmer weather will see it play a bigger role and it’s expected to overtake coal in either 2019 or 2020.

What is unlikely to change in the near-future, however, is the position at the top. In 2018 gas generated 115 TWh – more than nuclear and wind combined. But this is just one constant in a future of multiple moving and uncertain parts.

2019: a year of unpredictability

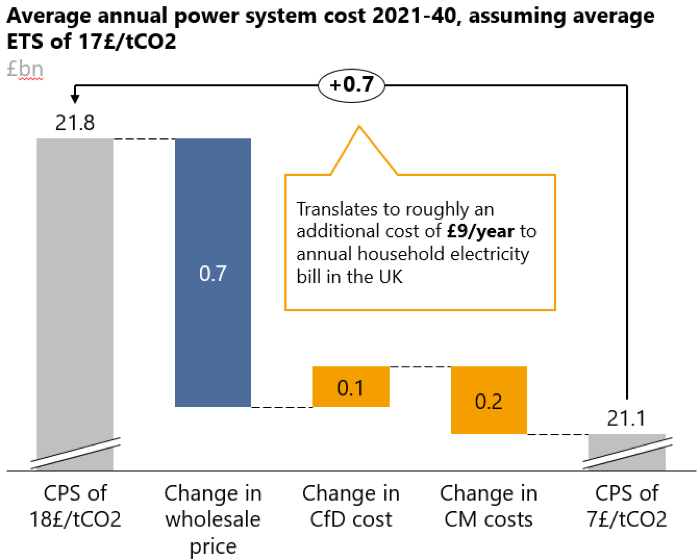

Britain is on course to leave the EU on 29 March. The effects this will have on the electricity system are still unknown, but one influential factor could be Britain’s exit from the Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS), the EU-wide market which sets prices of carbon emitted by generators. This may mean that rather than paying a carbon price on top of the ETS, as is currently the case, Britain’s generators will only have to pay the new, fixed carbon tax of £16 per tonne the UK government says will come into play in April, topped up by the carbon price support (CPS) of £18/tonne.

Lower prices for carbon relative to the fluctuating ETS + CPS, could make coal suddenly economically viable again. The black stuff could potentially become cheaper than other power sources. This about-turn could cause the carbon intensity of electricity generation to bounce up again in one or more years between 2019 and 2025, the date all coal power units will have been decommissioned.

The knock-on effect of lower carbon prices, combined with fluctuations in the Pound against the Euro, could see a reverse from imports to exports as Britain pumps its cheap, potentially coal-generated, electricity over to its European neighbours. That’s if the interconnectors can continue to function as efficiently as they do at present, which some parties believe won’t be the case if human traders have to replace the automatic trading systems currently in place.

Sizewell B Nuclear Power Station

A reversal of importing to exporting could also reduce the amount of nuclear electricity coming into the country from France. Future nuclear generation in Britain also looks in doubt with Toshiba and Hitachi’s decisions to shelve their respective plans for new nuclear reactors, which could leave a 9 GW hole in the low-carbon base capacity that nuclear normally provides.

Renewables have the potential to fill the gap and become an even bigger part of the electricity system, but this will require a push for new installations. 2018 saw a 60% drop in new wind and solar installations and less than 2 GW of new renewable capacity came onto the system, making it the slowest year for renewable growth since 2010.

Britain’s electricity has seen significant change over the last decade and 2018 once again saw the country take significant strides towards a low carbon future, but challenges lie ahead. Records might be harder to break, but it is important the momentum continues to move towards renewable, sustainable electricity.

Plants absorbing CO2 through photosynthesis is the most-commonly known part of the carbon cycle, however, rocks also absorb CO2 as they weather and erode.

Plants absorbing CO2 through photosynthesis is the most-commonly known part of the carbon cycle, however, rocks also absorb CO2 as they weather and erode.

This Carbon Price Support has had a huge impact, particularly on coal. Prior to its introduction, coal represented 50% of power generation but since it has fallen to record lows. 2017 saw the first day without any coal on the power system since the industrial revolution. Records continue to be broken throughout 2018, with

This Carbon Price Support has had a huge impact, particularly on coal. Prior to its introduction, coal represented 50% of power generation but since it has fallen to record lows. 2017 saw the first day without any coal on the power system since the industrial revolution. Records continue to be broken throughout 2018, with

And it starts with

And it starts with