Tackling climate change and spurring a global transition to net zero emissions will require collaboration between science and industry. New technologies and decarbonisation methods must be rooted in scientific research and testing.

Drax has almost a decade of experience in using biomass as a renewable source of power. Over that time, our understanding around the effectiveness of bioenergy, its role in improving forest health and ability to deliver negative emissions, has accelerated.

Research from governments and global organisations, such as the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) increasingly highlight sustainably sourced biomass and bioenergy’s role in achieving net zero on a wide scale.

The European Commission has also highlighted biomass’ potential to provide a solution that delivers both renewable energy and healthy, sustainably managed forests. Frans Timmermans, the executive vice-president of the European Commission in charge of the European Green Deal has emphasised it’s importance in bringing economies to net zero, saying: “without biomass, we’re not going to make it. We need biomass in the mix, but the right biomass in the mix.”

The role of biomass in a sustainable future

Moving away from fossil fuels means building an electricity system that is primarily based on renewables. Supporting wind and solar, by providing electricity at times of low sunlight or wind levels, will require flexible sources of generation, such as biomass, as well as other technologies like increased energy storage.

In the UK, the Climate Change Committee’s (CCC) Sixth Carbon Budget report lays out its Balanced Net Zero Pathway. In this lead scenario, the CCC says that bioenergy can reduce fossil emissions across the whole economy by 2 million tonnes of CO2 or equivalent emissions (MtCO2e) per year by 2035, increasing to 2.5 MtCO2e in 2045.

Foresters in working forest, Mississippi

Biomass is also expected to play a crucial role in supplying biofuels and hydrogen production for sectors of the global economy that will continue to use fuel rather than electricity, such as aviation, shipping and industrial processes. The CCC’s Balanced Net Zero Pathway suggest that enough low-carbon hydrogen and bioenergy will be needed to deliver 425 TWh of non-electric power in 2050 – compared to the 1,000 TWh of power fossil fuels currently provide to industries today.

However, bioenergy can only be considered to be good for the climate if the biomass used comes from sustainably managed sources. Good forest management practises ensure that forests remain sustainable sources of woody biomass and effective carbon sinks.

A report co-authored by IPCC experts examines the scientific literature around the climate effects (principally CO2 abatement) of sourcing biomass for bioenergy from forests managed according to sustainable forest management principles and practices.

The report highlights the dual impact managed forests contribute to climate change mitigation by providing material for forest products, including biomass that replace greenhouse gas (GHG)-intensive fossil fuels, and by storing carbon in forests and in long-lived forest products.

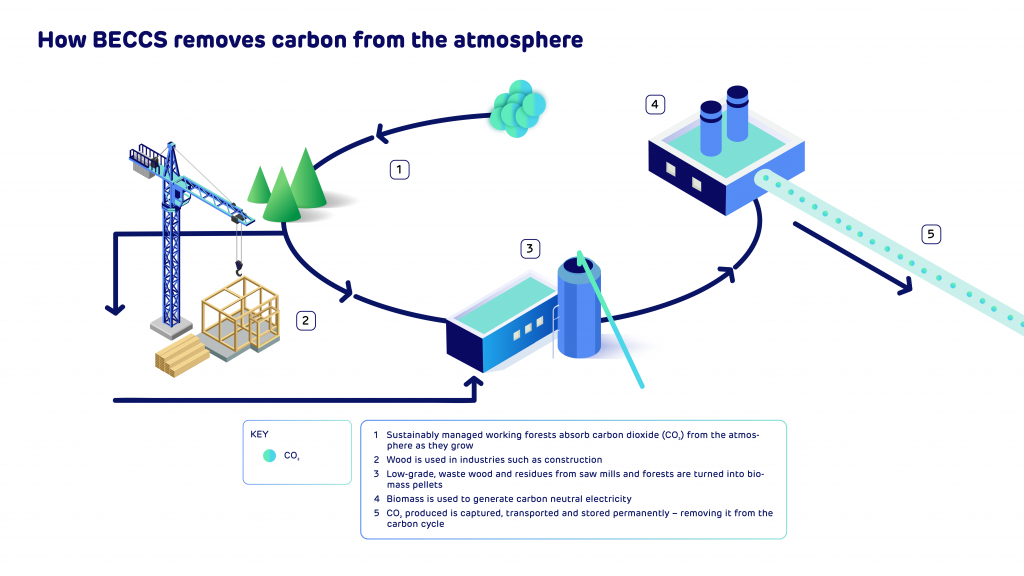

The role of biomass and bioenergy in decarbonising economies goes beyond just replacing fossil fuels. The addition of carbon capture and storage (CCS) to bioenergy to create bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS) enables renewable power generation while removing carbon from the atmosphere and carbon cycle permanently.

The negative emissions made possible by BECCS are now seen as a fundamental part of many scenarios to limit global warming to 1.5oC above pre-industrial levels.

BECCS and the path to net zero

The IPCC’s special report on limiting global warming to 1.5oC above pre-industrial levels, emphasises that even across a wide range of scenarios for energy systems, all share a substantial reliance on bioenergy – coupled with effective land-use that prevents it contributing to deforestation.

The second chapter of the report deals with pathways that can bring emissions down to zero by the mid-century. Bioenergy use is substantial in 1.5°C pathways with or without CCS due to its multiple roles in decarbonising both electricity generation and other industries that depend on fossil fuels.

However, it’s the negative emissions made possible by BECCS that make biomass instrumental in multiple net zero scenarios. The IPCC report highlights BECCS alongside the associated afforestation and reforestation (AR), that comes with sustainable forest management, are key components in pathways that limit climate change to 1.5oC.

Graphic showing how BECCS removes carbon from the atmosphere. Click to view/download

There are two key factors that make BECCS and other forms of emissions removals so essential: The first is their ability to neutralise residual emissions from sources that are not reducing their emissions fast enough and those that are difficult or even impossible to fully decarbonise. Aviation and agriculture are two sectors vital to the global economy with hard-to-abate emissions. Negative emissions technologies can remove an equivalent amount of CO2 that these industries produce helping balance emissions and progressing economies towards net zero.

The second reason BECCS and other negative emissions technologies will be so important in the future is in the removal of historic CO2 emissions. What makes CO2 such an important GHG to reduce and remove is that it lasts much longer in the atmosphere than any other. To help reach the Paris Agreement’s goal of limiting temperature rises to below 1.5oC removing historic emissions from the atmosphere will be essential.

In the UK, the CCC’s 2018 report ‘Biomass in a low-carbon economy’ also points to BECCS as both a crucial source of energy and emissions abatement.

It suggests that power generation from BECCS will increase from 3 TWh per year in 2035 to 45 TWh per year in 2050. It marks a sharp increase from the 19.5 TWh that biomass (without CCS) accounted for across 2020, according to Electric Insights data. It also suggests that BECCS could sequester 1.1 tonnes of CO2 for every tonne of biomass used, providing clear negative emissions.

However, the report makes clear that unlocking the potential of bioenergy and BECCS is only possible when biomass stocks are managed in a sustainable way that, as a minimum requirement, maintains the carbon stocks in plants and soils over time.

With increased attention paid to forest management and land use, there is a growing body of evidence that points to bioenergy as a win-win solution that can decarbonise power and economies, while supporting healthy forests that effectively sequester CO2.

How bioenergy ensures sustainable forests

Biomass used in electricity generation and other industries must come from sustainable sources to offer a renewable, climate beneficial [or low carbon] source of power.

UK legislation on biomass sourcing states that operators must maintain an adequate inventory of the trees in the area (including data on the growth of the trees and on the extraction of wood) to ensure that wood is extracted from the area at a rate that does not exceed its long-term capacity to produce wood. This is designed to ensure that areas where biomass is sourced from retain their productivity and ability to continue sequestering carbon.

Ensuring that forestland remains productive and protected from land-use changes, such as urban creep, where vegetated land is converted into urban, concreted spaces, depends on a healthy market for wood products. Industries such as construction and furniture offer higher prices for higher-quality wood. While low-quality, waste wood, as well as residues from forests and wood-industry by-products, can be bought and used to produce biomass pellets.

A report by Forest 2 Market examined the relationship between demand for wood and forests’ productivity and ability to sequester carbon in the US South, where Drax sources about two-thirds of its biomass.

The report found that increased demand for wood did not displace forests in the US South. Instead, it encouraged landowners to invest in productivity improvements that increased the amount of wood fibre and therefore carbon contained in the region’s forests.

A synthesis report, which examines a broad range of research papers, published in Forest Ecology and Management in March of 2021, concluded from existing studies that claims of large-scale damage to biodiversity from woody biofuel in the South East US are not supported. The use of these forest residues as an energy source was also found to lead to net GHG greenhouse emissions savings compared to fossil fuels, according to Forest Research.

Importantly the research shows that climate risks are not exacerbated because of biomass sourcing; in fact, the opposite is true with annual wood growth in the US South increasing by 112% between 1953 and 2015.

Delivering a “win-win solution”

The European Commission’s JRC Science for Policy literature review and knowledge synthesis report ‘The use of woody biomass for energy production in the EU’ suggests a win-win forest bioenergy pathway is possible, that can reduce greenhouse gas emissions in the short term, while at the same time not damaging, or even improving, the condition of forest ecosystems.

However, it also makes clear “lose-lose” situations is also a possible, in which forest ecosystems are damaged without providing carbon emission reductions in policy-relevant timeframes.

Win-win management practices must benefit climate change mitigation and have either a neutral or positive effect on biodiversity. A win-win future would see the afforestation of former arable land with diverse and naturally regenerated forests.

The report also warns of trade-offs between local biodiversity and mitigating carbon emissions, or vice versa. These must be carefully navigated to avoid creating a lose-lose scenario where biodiversity is damaged and natural forests are converted into plantations, while BECCS fails to deliver the necessary negative emissions.

In a future that will depend on science working in collaboration with industries to build a net zero future continued research is key to ensuring biomass can deliver the win-win solution of renewable electricity with negative emissions while supporting healthy forests.