If the rapid rise of electric vehicles (EVs) over the last decade tells us anything it’s this: the future of transport is electric. But while EVs may be the fast-growing future of mobility, their beginnings stretch right back to the days of the first automobiles.

Today we associate EVs with hallmark tech innovators like Elon Musk and his Teslas, but the original electric vehicle had a much more humble beginning – in a 19th century workshop in Scotland, owned by a chemist named Robert Davidson.

Realising the potential of electric transport

‘Barking up the wrong (electric motor) tree’ by B. Bowers, Proceedings of the IEEE 2004

Using electricity to power transport has long made sense as a means of moving around quickly and efficiently. Robert Davidson of Aberdeen understood this as early as 1837, when he created his first electric motor – powered by zinc-acid batteries.

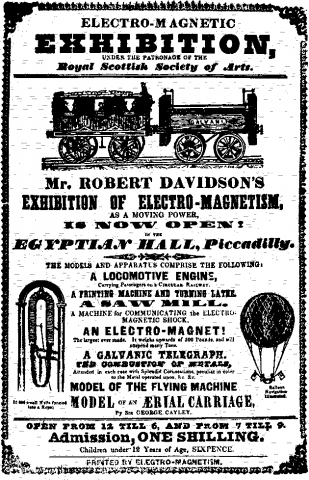

While Davidson was a chemist, he had a fascination with tinkering and engineering. Two years after creating his first motor, he invited visitors to his ‘Electromagnetic Exhibition’ where they could see a fully visualised electric model train capable of carrying two people at a time. He would go on to develop a prototype dubbed the ‘Galvani’, which he tested on the Edinburgh-Glasgow Railway in 1842, reaching a maximum speed of 4 miles per hour.

Davidson overcame the hurdle of finding a battery strong enough to power a full-sized train by using liquid chemical batteries rather than solid ones. However, when they ran flat, the chemicals had to be completely replaced. There was a further spanner in the works when railway workers destroyed his locomotive fearing the move toward electric vehicles would put them out of a job.

It wasn’t until 1884 that the first production-standard electric car capable of being reproduced and sold to the public was unveiled. The man behind this was Thomas Parker, who was also responsible for electrifying the London Underground.

His car was born out of a desire to minimise smoke and pollution in London, a purpose which still rings true over 135 years later. More practical uses for these vehicles sprung from Parker’s initial foray, with electric wagons being instituted in mines so their motors wouldn’t pollute the air.

The Parker Electric, 1890, invented by Thomas Parker

The Golden Age

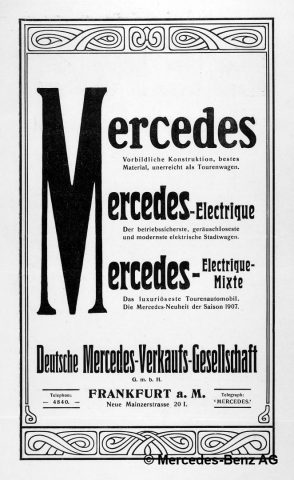

Mercedes-Electrique advertisement from 1907 © Daimler AG.

EVs came into their own in the early 1900s, when popularity in Europe and America surged. Unlike gasoline (at the time, petrol was the primary fuel source) EVs did not produce a strong stifling smell, nor did they require gear changes or manual effort to start them, such as using a hand crank.

It was during this period that many well-known car manufacturing names began experimenting with electricity. Ferdinand Porsche – founder of the eponymous sports car –produced an electric vehicle called ‘P1’ in 1898, before creating the world’s first hybrid offering, which was powered by both electricity and a combustion engine. Mercedes-Benz also offered up an electric model called the Mercedes Mixte, in 1906. This car was adopted as a taxi in cities and was even developed into a race car in 1907.

No longer seen as a threat to the existing coal-powered transport, the EVs of the time were limited by the charge in their batteries, but experienced a vogue as ‘city cars’ for the rich who wanted to travel short distances in style. Sales peaked in the early 1900s, when roughly one-third of all cars on US roads were electric.

But EVs first Golden Age came to an abrupt end in the 1920s with the arrival of the man whose name would become synonymous with car manufacturing the world over: Henry Ford.

The rise of petrol

When Ford’s Model T parked on the scene, it brought with it affordable, mass produced petrol-powered transport – EV popularity quickly began its descent. Their limited battery capacities had become a downside as road networks expanded, and the discovery of more petroleum deposits meant that gasoline was more readily available and cheaper than recharging batteries.

Electric milk float in Barnet, London, 1970

One of the only EVs that survived the next few decades was the quintessentially British milk float, which made up the majority of global EVs for most of the 20th century. Away from milk rounds and golf carts, the entire electric automobile industry went silent and the technology stagnated – it looked like gasoline was here to stay.

That was, until a very special electric car took a spin in outer space.

The moon is the limit

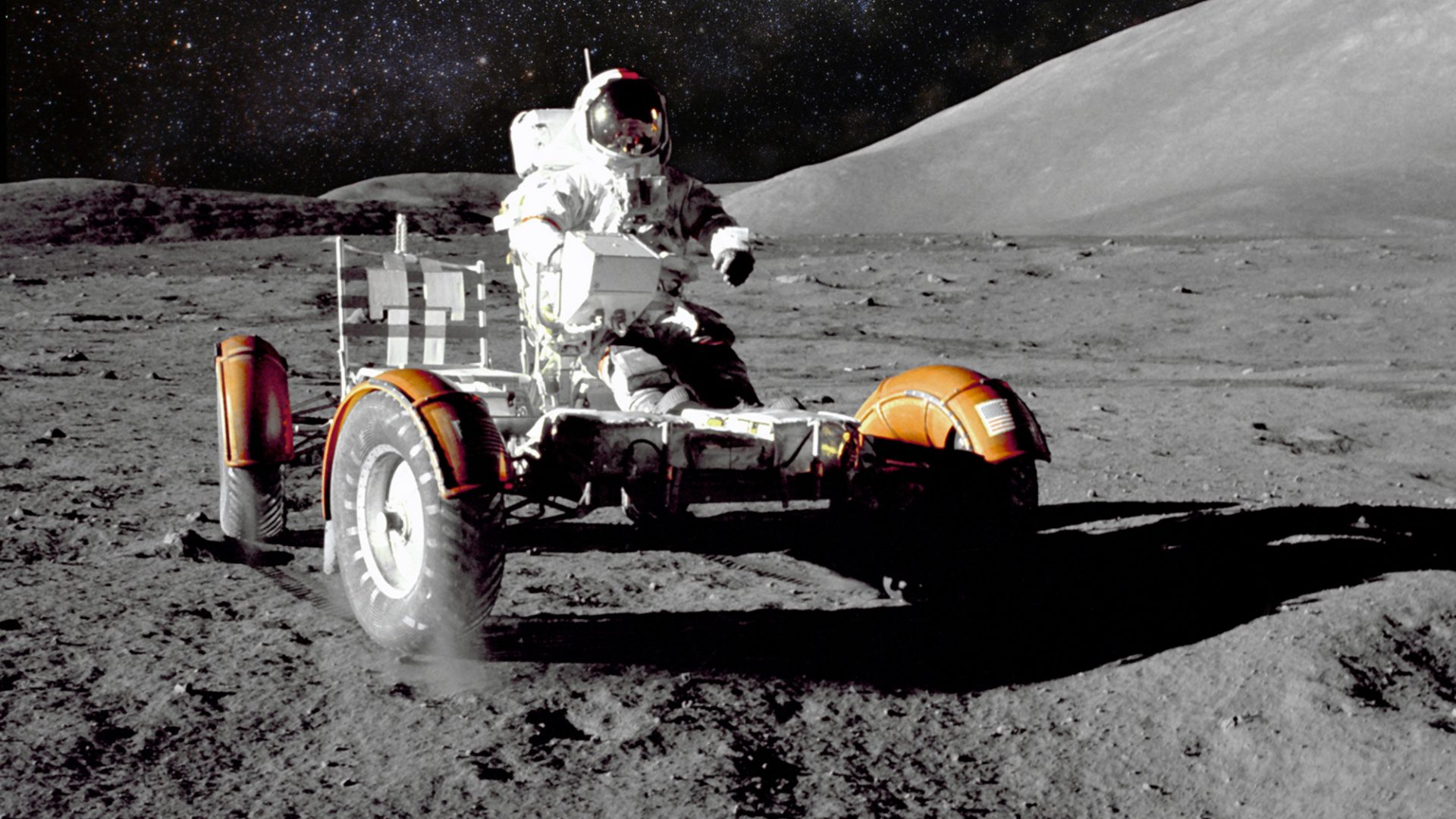

In the summer of 1971, the world was glued to TV sets as the Apollo 15 mission to the moon unfolded, featuring a special guest – the new Lunar Roving Vehicle, which ran on battery power. There are currently three rovers parked on the moon, and their continued evolution helped renew interest in electric powered vehicles throughout the 1960s and 70s. It led to a few new battery-powered concept cars appearing, manufactured by General Motors.

Apollo programme lunar rover

Now powered by lithium or nickel-cadmium batteries, these cars provided a viable option for those concerned about the economic fluctuations of the oil and gas industries, with electricity not as exposed to market changes.

The pace of EV innovation picked up after the development of the lithium-ion battery, which significantly extended life and power output, opening the potential for electric vehicles to become more than just short distance city cars.

These cars weren’t produced en masse until the 2000s, after more than three decades of the global environmental movement and its influence over public policy.

As the technology caught up with an ambition to find a practical alternative to fossil fuel powered transport, the EV entered its second golden age.

Tesla driving towards onshore wind farm

Where are we now?

Today there are over 273,000 electric cars on Britain’s roads, but this is set to grow quickly and significantly. By 2025 it’s estimated there will be 1 million EVs on UK roads – by 2040 there could be as many as 11 million.

Most mainstream car producers are now racing to take the lead in the EV market, from the headline grabbing antics of Tesla to the petrol-powered stalwarts of Volkswagen, Nissan and even Ford. And it’s not just the personal vehicle industry where electricity is racing ahead as a fuel source. Everything from inner-city scooters to the rapidly-evolving aviation industry are being electrified – the first electric passenger jet could be ready for take-off as soon as 2027.

Powering the way that we travel has become one of the most important conversations around the future of transport – and taking a look into the past suggests that this time electric vehicles are here to stay.