Batteries can be found everywhere: in our houses, in our cars and vans and even in the tech we wear. More than just being pervasive, battery technology has enabled a huge amount of technological breakthroughs – from the increasing distances electric vehicles can travel between charges, to being able to store renewable electricity for when it’s needed.

These two developments in particular – emission-free electric transport and grid-scale batteries that can power homes, businesses and cities even when energy sources are not generating – could be two key aspects in the transition to a zero carbon energy future. However, questions remain around batteries’ environmental impact.

What’s in our batteries?

The batteries we use every day are typically made from a mix of metals and chemicals such as lead and acid (as found in petrol and diesel-engine cars), or zinc, carbon, nickel and cadmium, which make up some of the batteries found in the home.

Then there’s lithium-ion. The go-to material mix for the rechargeable batteries powering mobile phones, laptops and, more recently, a high proportion of electric vehicles around the world.

The surge in the production of lithium-ion batteries over the last decade has led to an 85% price reduction, which in turn, has encouraged the use of these reliable batteries in electric vehicles and large-scale energy storage solutions. While this is a positive step in the development of rechargeable goods, it raises issues in the handling of spent batteries.

Each year around 600 million batteries are thrown away in the UK alone – even rechargeable batteries have a shelf-life. While recycling allows the safe extraction of raw materials for use in other industries and products, the majority of discarded batteries are left to rot in landfill sites. This can lead to their chemical contents leaking into the ground causing soil and water pollution.

For batteries of any size to play a role in a sustainable future, an overhaul is needed in preventing harmful levels of battery waste.

The battery problem

Although the number of batteries that are recycled has increased, currently the EU puts the recycling efficiency target for a lithium battery at only 50% of the total weight of the battery.

Connecting positive and negative terminals on a rechargeable lithium mobile battery

Standard recycling methods achieve this by separating and processing the plastics and wiring that make up the bulk of the battery pack, then smelting and extracting the copper, cobalt and nickel found within the cell, releasing carbon dioxide in the process. Crucially, these recycling practices do not typically recover the aluminium, lithium or any of the organic compounds within the battery, meaning that only around 32% of the battery’s materials can be reused. A lack of recycling facilities in the UK means spent batteries have traditionally been exported overseas for treatment, upping emissions even further.

It is not only spent batteries that cause a problem, the creation of them can be harmful too. For example, lithium mining can pose health hazards to miners and damage local communities and their environments.

In one area of Chile, 65% of available water is used in the production of lithium for batteries, meaning water for other uses, such as maintaining crops, must be driven in from somewhere else, impacting farmers greatly. There are also risks around contaminated water leaking into livestock and human water supplies, as well as causing soil damage and air pollution.

As a result, teams across the globe are working to make the production and recycling of batteries more efficient and eco-friendly.

Switching materials

Researchers based at Chalmers University of Technology in Sweden and the National Institute of Energy in Slovenia, are developing an aluminium-ion battery. This type of battery offers a promising alternative to lithium-ion due to the abundance of aluminium in the Earth’s crust and its ability, in principle, to carry charges better than lithium.

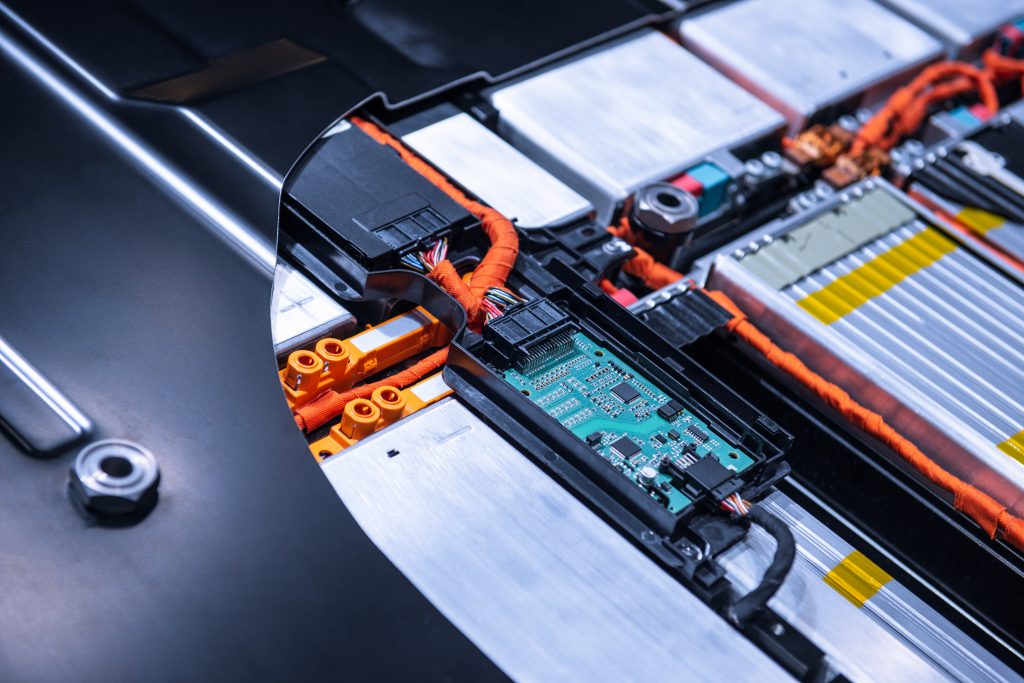

Disassembling the battery from an electric vehicle (EV)

The reduction in material and environmental costs that come with using aluminium over lithium might mean batteries made with it could offer more affordable, large-scale storage for renewable installations.

While more research is still needed to reduce the size and control the temperature of aluminium batteries, researchers believe they will soon enter commercial production and eventually could replace their lithium-ion predecessors.

Elsewhere, IBM Research’s Battery Lab is developing a sustainable battery solution made predominantly of materials extracted from seawater, a composition that would avoid the concerns associated with the production of lithium-ion cells.

While the exact combination of materials in not public, Battery Lab claims the new concept has outperformed its lithium-ion counterpart in energy density, efficiency, production costs and charging time.

Making good of the old

Along with advancements in battery development, new recycling methods are also reducing the environmental impact of batteries.

German company, Duesenfeld, is innovating the recycling of lithium-ion batteries used in electric vehicles through an innovative new process.

Batteries are first discharged and disassembled into their constituent parts. The metals are extracted with a water-based solution, the liquid chemicals evaporated and condensed, and the dry materials crushed and separated, ready for reuse. Importantly, Duesenfeld’s method avoids incineration, reducing the carbon footprint of lithium-ion battery recycling by 40% and enabling over 90% of the batteries’ materials to be salvaged and reused in new batteries.

Fortum, a Finnish energy company, is exploring a similar process, with the potential to recycle more than 80% of battery materials, including cobalt, manganese and nickel.

This year Fortum signed a deal with German chemical company BASF and Russian mining and smelting firm Nornickel to develop a renewable-powered, electric vehicle battery recycling cluster in Finland. The aim is to create a ‘closed-loop’ battery production and recycling system, meaning materials from recycled batteries would be used to make new batteries.

While it is clear there is a long way to go in reducing the environmental impact of battery production and recycling, continued development of both batteries and technology can pave a path for a cleaner, safer, battery-powered, zero carbon future.

Electric vehicle battery pack

EV fast facts from Electric Insights:

- Electric vehicles (EVs) on roads in Great Britain – including EV vans – emit on average just one quarter the carbon dioxide (CO2) of conventional petrol and diesel vehicles

- If the carbon emitted in making their battery is included, this rises to only half the CO2 of a conventional vehicle

- EVs bought last year could be emitting just a tenth that of a petrol car in four years’ time, as the electricity system continues to decarbonise