In homes and offices, on streets and in shops, there are more electronic devices than ever. However, for all the phones, washing machines and TVs British consumers are plugging in, our electricity consumption has been on a downward tick – and has been since the middle of the last decade.

At the same time, an increasing percentage of our demand is being met by renewable and low-carbon energy sources. By 2016, greenhouse gas emissions from electricity had dropped to 62% below 1990 levels, helping the UK get close to meeting its third carbon budget target.

It’s the power sector that has seen the biggest reductions through the decline of coal, the greater use of gas and the rise of renewables. There are still big strides to make in the economy as a whole – particularly in sectors such as heat, transport and buildings. But there are positive signs of transformation that could help the country reach its fifth carbon budget goal of lowering emissions by 57% between 1990 and 2030.

Will 2018 prove to be another milestone year for Great Britain’s electricity system? And could the electrification of the economy help other sectors step-up their own decarbonisation?

The efficiency transformation

Reduced demand for electricity comes, in part, as a result of the decline in energy-intensive, manufacturing and heavy industry. However, in the domestic sector the decline has been equally significant. Since 2002, energy consumption in the home has fallen 19% from 52,229 ktoe (Kilotonne of Oil Equivalent) to 42,486 ktoe. As well as electricity, this includes gas, solid fuels such as coal and more.

This drop comes despite a growing population, economic growth, an increase in the number of households and a rising number of consumer devices and appliances. So, what exactly is bringing down energy consumption?

One cause is the increased efficiency of electronics and appliances. The phasing out of incandescent lightbulbs – which had hardly changed since Edison’s day – in favour of energy-saving models such as LEDs has reduced electricity used to light homes by a third since 1997. As well as the improved efficiency of large appliances, like fridge freezers, there is also a greater consumer awareness of electricity saving habits, such as washing clothes at lower temperatures.

The increase in small, battery-powered devices, such as smartphones, tablets and laptops on the other hand, means we’re spending less time using higher-powered equipment that constantly pulls from the grid, such as TVs and hi-fis.

What this can lead to, however, is a change in the shape of electricity demand (the ‘shape’ of power demand can be explored in Electric Insights). For example, overnight when many people choose to charge those battery-powered appliances. Such changes in demand present a challenge to forecasters at in National Grid’s control room, who predict ahead when, where and how much power will be needed from the country’s electricity grid.

Shifting demand spikes

Today’s peak electricity demand times remain relatively unchanged from the 20th century. People still come home and turn on lights, kettles and washing machines at around 5pm and 6pm.

But as artificial intelligence makes its way into more and more home appliances, these spikes are likely to level out across the day. Connected devices will aim to predict peak times and, where such tariffs are provided by energy suppliers, only run when overall demand costs are lower.

At the same time, lifestyles have changed, affecting electricity demand even further. In the past some of the biggest surges in UK electrical history came in the immediate aftermath of big TV moments, when people across the country switched on kettles, opened fridges and went to the toilet.

Now the proliferation of on-demand and online TV has reduced the need for National Grid to keep power stations on standby during major televised moments, as people choose to watch at their leisure rather than when they are broadcast.

Sports, however, remains one of the things that still attracts large numbers of live viewers. This June’s football World Cup means the National Grid will be braced for any surges in post-penalty shootout tea breaks.

Combined with a Royal Wedding – the last of which caused a significant spike – summer 2018 could see a few rare moments when mass TV viewing shunts electricity demand enough for it to be noticeable.

Cleaner power

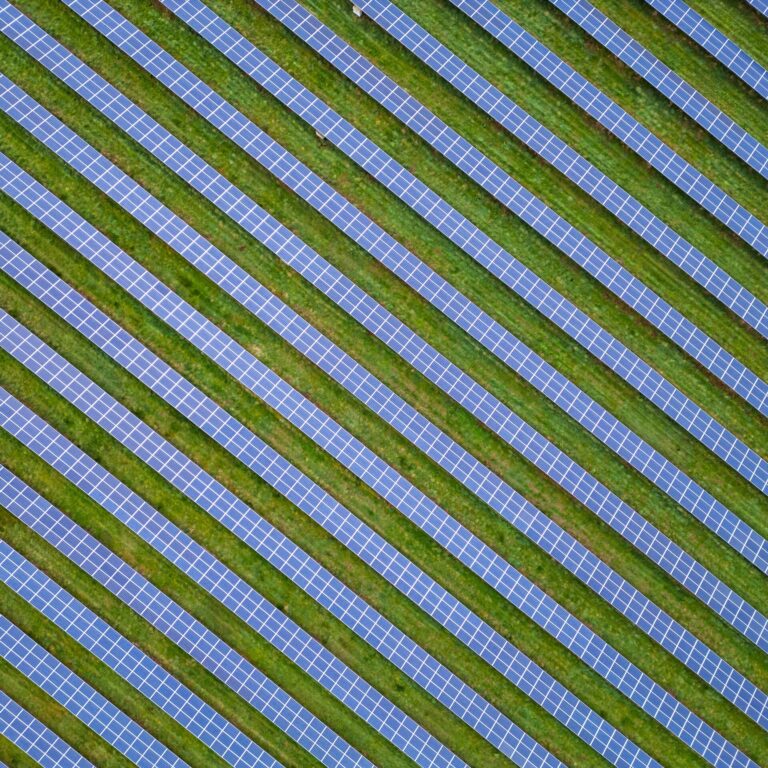

But while 2018 may see some instances where demand surges, it’s likely power generation will continue to grow cleaner. The Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) has released projections suggesting installed renewable electricity capacity could reach 36 gigawatts (GW) by 2030 – building on a 900% increase between 2007 and 2017.

It is, of course, important we continue to use electricity more efficiently. In 15 years from now, it’s predicted that power generation could begin to rise significantly and so decarbonising the production of power is arguably just as important as saving it.

This year will see another, flexible 600+ megawatt (MW) coal unit converted to sustainable biomass at Drax Power Station in Yorkshire and the first of 84 offshore wind turbines turned on as part of the 588MW Beatrice project in the Outer Moray Firth. These developments will quicken the pace of decarbonisation in Great Britain’s electricity network, meaning that positive trend that will continue.

This is the second story in a series on electricity demand through the ages, the first of which looked at the 1970s.