Scotland’s landscape is defined by its weather. The millennia of wind, rain and snow has battered the country, ebbing away at its rivers, mountains, valleys and deep lochs forged by ice ages and volcanos. Weather also plays an important role in the country’s power generation. The country has more than 9 gigawatts (GW) of installed wind power – enough to sometimes meet double Scotland’s electricity demand – as well as having a long history of hydropower.

But while it is an intrinsic part of the country, Scotland’s weather can be anything but pleasant. Rain can be persistent and when the temperature drops in winter, it turns to snow – a lot of it. Scotland gets more snow than any other part of the UK.

Scottish poet Robert Burns described the harshness of the winter months in his 1781 poem Winter A Dirge:

“The wintry west extends his blast,

And hail and rain does blaw;

Or the stormy north sends driving forth

The blinding sleet and snaw:”

Sleet and ‘snaw’ (snow) fall occurs on average for 38 days a year in Scotland, compared to an average of 23 days across the rest of the United Kingdom, and can remain covering mountaintops long into spring.

Ben Cruachan

The peak of Ben Cruachan in the Western Highlands is no exception. Cruachan Power Station, on the slopes of the mountain, however, must be ready to either generate or absorb electricity through all forms of weather – even the most severe.

“On a few occasions the snowfall has been so extreme that we’ve been unable to access the dam for a few weeks at a time,” says Gordon Pirie, a Civil Engineer at Cruachan. “Thankfully, we have enough controls in place where we are still able to monitor and operate things remotely.”

Mountain road from Cruachan Power Station to its dam blocked due to snow

This mountainside location and winter weather can make for tough working conditions, but Cruachan is designed to handle it. In fact, in some cases it benefits from it.

Taking advantage of wet weather

Cruachan is built around the geography and climate of the Highlands. It stores water in an upper reservoir 400 meters (1,312 feet) up Ben Cruachan and uses its elevation to run it down the mountain, spin a turbine and generate power.

And when there is excess electricity being generated nationally, the same turbines reverse and use the excess electricity to pump water from Loch Awe up to the reservoir, helping to balance the grid. This acts as a form of energy storage by essentially stockpiling the excess electricity in the form of water held in the top reservoir.

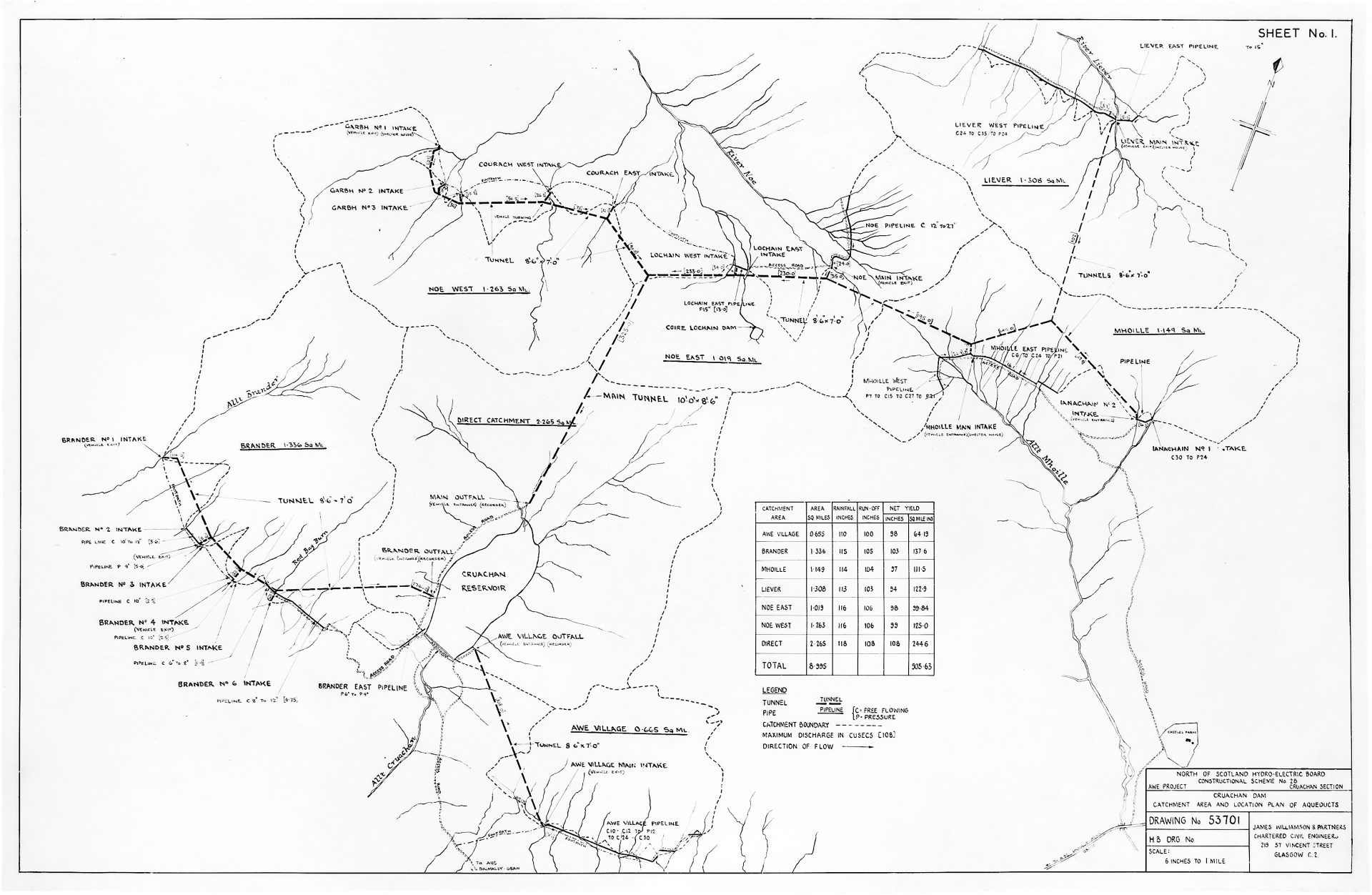

For the most part the water used to generate electricity comes exclusively from Loch Awe and is passed up and down the mountain. However, 10% of it comes for ‘free’, as it’s collected from natural rainfall and surface water that makes its way to the upper reservoir through Cruachan’s aqueducts. This system of 14 kilometres of interconnected concrete pipes covers a 23 square kilometre radius around the reservoir and is designed to bring in water from 75 intakes dotted around the top of the mountain.

A North of Scotland Hydro-Electric Board diagram from c.1960s showing the aqueducts feeding Cruachan’s dam; click to view/download.

Some of these intakes are as small as street drains, while others are large enough to drive a Land Rover into. It’s part of Pirie’s job to keep them in good working order so they continue to deliver water to the reservoir. As the intakes are scattered around the mountaintop, they must be able to deal with whatever the Scottish winter throws at them.

Gordon Pirie, Civil Engineer and Cruachan Power Station dam

“Even in freezing conditions the water will still flow through the aqueduct system, the intakes have a built-in feature which allows the water to flow into them even if the surface is frozen solid,” explains Pirie. “Any snow or frost on the ground eventually thaws and makes its way to the reservoir.”

As spring arrives and snow begins to thaw across the Highlands, greater volumes of water will run off into the reservoir and the power station’s engineers work to manage the water level.

Keeping water pressure under control

Thawing snow can bring greater volumes of water into the reservoir.

The power station must be able to pump water and absorb excess electricity from the grid at a moment’s notice. This ability to turn excess electricity into stored energy makes Cruachan hugely useful in controlling the grid’s voltage, frequency and in keeping it stable. However, there must be enough space available in the reservoir for the water being pumped up the mountainside to enter – even when excessive rainfall or melting snow begins to naturally fill it up.

The power station can control the reservoir levels through a number of means. This includes the ability to close off an aqueduct, or to run the turbines without generating electricity so the team can move water from the reservoir into Loch Awe below.

If the water level and pressure on the dam reaches dangerous levels a ‘dispenser valve’ can be opened in an emergency, sending a jet of water flying out the dam to cascade safely down the mountainside. However, outside of testing, this has never been necessary to do.

And while the weather might be the most persistent natural force the power station must deal with, it’s not the only one. “Recently we had an issue with a bat roosting within one of the tunnels in which we were carrying out stabilisation works,” recalls Pirie. “It was looking for a suitable location to hibernate for the winter and the tunnel provided the ideal environment. We had to stop works to have a bat survey undertaken and apply for a bat license.”

Cruachan’s location makes for stunning views of the Highlands, but occasionally brutally cold and perilously wet conditions come with the territory. For the power station team, working with the sometimes-despairing weather is all part of what allows the Hollow Mountain to operate as it has done for more than half a century.

The Highlands around Ben Cruachan are rich with wildlife. Educational information on area’s flora and fauna can be explored at the Cruachan Power Station visitor centre.

Visit Cruachan — The Hollow Mountain to take the power station tour.