Travelling through the Highlands towards the West Coast of Scotland, you pass the mighty Ben Cruachan – its 1,126 metre peak towers over the winding Loch Awe beneath. It is the natural world on a huge scale, but within its granite core sits a manmade engineering wonder: Cruachan Power Station.

Opened by The Queen in 1965, it is one of only four pumped-hydro stations in the UK and today remains just as impressive an engineering feat as when it was first opened.

Cruachan is operated safely and hasn’t had a lost time injury in 15 years. The robust health and safety policies and practices employed at the power station were not in place all those decades ago.

It took six years to construct, enlisting a 4,000-strong workforce who drilled, blasted and cleared the rocks from the inside of the mountain, eventually removing some 220,000 cubic metres of rubble. The work was physically exhausting – the environment dark and dangerous.

Nicknamed the ‘Tunnel Tigers’, the men that carried the work out came from far and wide, attracted to its ambition as well as a generous pay packet reflective of the danger and difficulty of the work. But few of them were fully prepared for the extent of the challenge.

One labourer, who started at Cruachan just after his 18th birthday, recalls: “I was in for a shock when I went down there. The heat, the smoke – you couldn’t see your hands in front of you.”

Inside the mountain

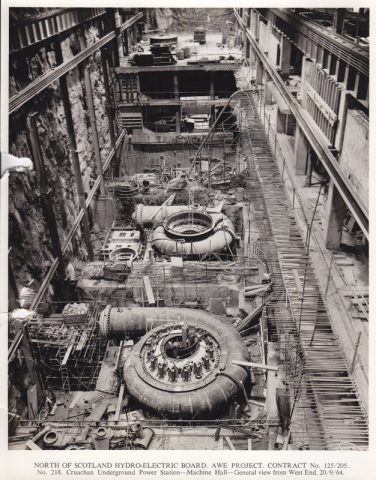

The work of hollowing out Ben Cruachan was realised by hand-drilling two-to-three metre deep holes into the granite rockface. An explosive known as gelignite, which can be moulded by hand, was packed into the drilled holes and detonated. The blasted rocks were removed by bulldozers, trucks and shovels, before drilling began on the fresh section of exposed granite. In total, 20km of tunnels and chambers were excavated this way, including the kilometre-long entrance tunnel and the 91-metre-long, 36-metre-high machine hall.

Wilson Scott was just 18 when he got a job working as a labourer at Cruachan while the machine hall was being cleared out.

“The gelignite, it had a smell. Right away I was told not to put it near your face,” he says, “It’ll give you a splitting headache and your eyes will close with the fumes that come off it. It was scary stuff.”

This process allowed for rapid expansion through the mountain. With three or four blasts each 12-hour shift, some 20 metres of rock could be cleared in the course of a day. Activity was constant, and to save the men having to make the journey back up to the surface, refreshments came to them.

“There was a bus that went down the tunnel at 11 o’clock with a huge urn of terrible tea,” says Scott. “Most of the windows were out of the bus because the pressure of the blasting had blown them in.”

The tea did little to make the environment hospitable, however. From the water dripping through the porous rocks making floors slippery and exposed electrics vulnerable, to the massive machinery rushing through the dense dust and smoke, danger was ever-present. Loose rocks as large as cars would often fall from exposed walls and ceilings while the regular blasting gave the impression the entire mountain was shaking.

“I’ll tell you something: going into that tunnel the first time,” Scott says. “It was a fascinating place, but quite a scary place too.

Above them, on top of the mountain, a similarly intrepid team tackled a different challenge: building the 316-metre-long dam. They may have escaped the hot and humid conditions at the centre of Cruachan, but their task was no less daunting.

On top of the dam

Out in the open, 400 metres above Loch Awe, the team were exposed to the harsh Scottish elements. John William Ross came to Cruachan at the age of 35 to work as a driver and spent time working in the open air of the dam. “You’d get oil skins and welly boots, and that was it. We didn’t have gloves, if your hands froze – well that’s tough luck isn’t it.” Mr Ross sadly passed away recently.

Charlie Campbell, a 19-year-old shutter joiner who worked on the dam found an innovative way around the cold. “You’d put on your socks, and then you’d get women’s tights and you’d put them over the top of the socks, and then you’d put your wellies on and that’d keep your feet a wee bit warmer. We thought it did anyway. Maybe it was just the thought of the women’s stockings.”

Pouring the concrete of the dam – almost 50 metres high at its tallest point – was precarious work, especially given the challenges of working with materials like concrete and bentonite (a slurry-like liquid used in construction).

“It was horrible stuff. It was like diarrhoea, that’s the only way of explaining it,” says Campbell. “There was a boy – Toastie – I can’t remember his real name. He fell into it. They had quite a job getting him out, they thought he was drowned, but he was alright.”

Many others were not alright. The danger of the work and conditions both inside and on top of the mountain meant there was a significant human cost for the project. During construction, 15 people tragically lost their lives.

Today a carved wooden mural hangs on the wall of the machine hall to capture and commemorate the myth of the mountain and the men who sadly died – a constant reminder of the bravery and sacrifice they made.

The men that made the mountain

The Cruachan ‘Tunnel Tigers’

The Tunnel Tigers were united in their efforts, but came from a range of backgrounds and cultures. Polish and Irish labourers worked alongside Scots, as well as displaced Europeans, prisoners of the second world war and even workers from as far as Asia. The men would work 12, sometimes 18-hour shifts, seven days a week. Campbell adds that some men opted to continue earning rather than rest by doing a ‘ghoster’, which saw them working a solid 36 hours.

Many men would make treble the salary of their previous jobs, with some receiving as much as £100 a week, at a time when the average pay in Scotland was £12. Some teams’ payslips were stamped with the words ‘danger money’ – illustrative of the men’s motivation to endure such life-threatening work.

While it was a dangerous and demanding job, many of the Tigers look back with fond memories of their time on the site and many stayed in the area for years after. “It was an experience I’m glad I had,” says Scott. “It puts you in good stead for the rest of your days.”

As for Cruachan Power Station, its four turbines are still relied on today by Great Britain to balance everyday energy supply. As the electricity system continues to change, the pumped hydro station’s dual ability to deliver 440 megawatts (MW) of electricity in just 30 seconds, or absorb excess power from the grid by pumping water from Loch Awe to its upper reservoir, is even more important than when it opened.

- Cruachan machine hall roof excavation, 1962

- Cruachan machine hall construction, 1964

- Cruachan machine hall, 2019

Standing at the foot of a mountain more than 50 years ago, the men about to build a power station inside a lump of granite may have found it unlikely their work would endure into the next millennium. They may have found it unlikely it was possible to build it at all. But they did and today it remains an engineering marvel, a testament to the effort and expertise of all those who made it.