It may be bulkier than its foreign cousins and its flat back might make it the perfect household booby trap, but the UK plug is a modern-day design marvel.

The UK’s ‘G Type’ (or BS 1363) plug is a product of the post-war age. But it has endured for the better part of a century, ensuring homes, business and sockets around the UK have access to safe, usable electricity. Even as the devices they power have changed, become smarter and more connected, the three-prong G Type remains unchanged.

But to understand how it came into being, it’s worth first understanding what makes it such a unique and clever bit of design – including its role in achieving the ambitions of one of Great Britain’s pioneering female engineers, and its money-saving abilities.

What makes Great Britain’s plugs special

The modern plug used across Great Britain (as well as Ireland, Cyprus, Hong Kong and Malaysia) is a smarter and more advanced item than many of its contemporaries. This is thanks to a number of key, but often overlooked, features.

A collection of international power point illustrations

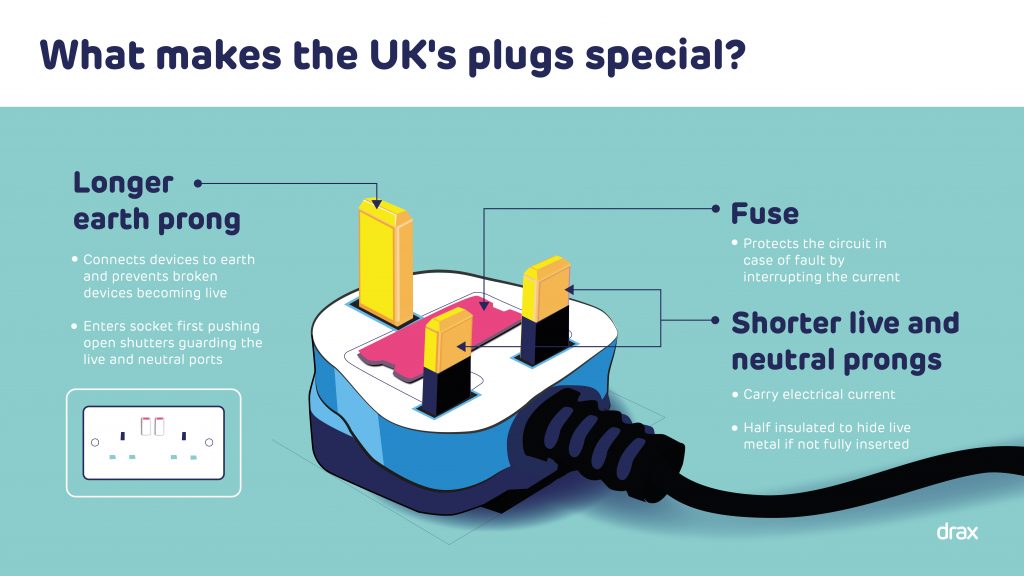

The first is its earth prong. Connecting the plug to the earth means if a wire comes loose in, say, a toaster and touches a metal part, the device will short circuit as the electricity runs through to make contact with the earth, rather than the entire item becoming electrified and dangerous.

The longer earth prong also plays the role of ‘gatekeeper’ for the entire plug. When a plug enters a socket the longer earth prong enters before any others, pushing back plastic shutters that sit over the live and neutral entrances. This means when there is no plug in a socket the live and neutral ports, which actually carry electric current to devices, are covered over making it very difficult for a child to push anything dangerous into the socket.

Another clever feature inside the Great British plug comes in the form of a fuse connected to the live wire. If there’s an unexpected electrical surge the fuse will blow and cut off the connected device, preventing fires and electrocutions.All packaged together, the G Type plug is far from the most compact version – yet it is hugely effective. However, these ideas didn’t come together at the flick of a switch.

Pre-war plugs

Going back to end of the 19th Century, the idea of owning devices you could move around your house and connect to the electricity circuit from different rooms was novel.

Electricity’s main role in homes was for lighting and was fixed into walls and ceilings, with their cables hidden. It wasn’t until the rise of new electrical appliances in the 20th century that the need for an easy way to plug electrical items into circuits arose.

A series of two-pronged plugs first emerged in 1883, but there was no standardisation of design which would allow any appliance to be plugged into any socket. That began to change in 1904, when US inventor Harvey Hubbell developed a plug that allowed non-bulb electrical devices to be connected into an existing light socket, eliminating the need for the installation of new sockets.

By 1911, a design for a three-pronged plug with an earth connection had emerged, with manufacturer AP Lundberg bringing the first of this kind of plug to Britain.

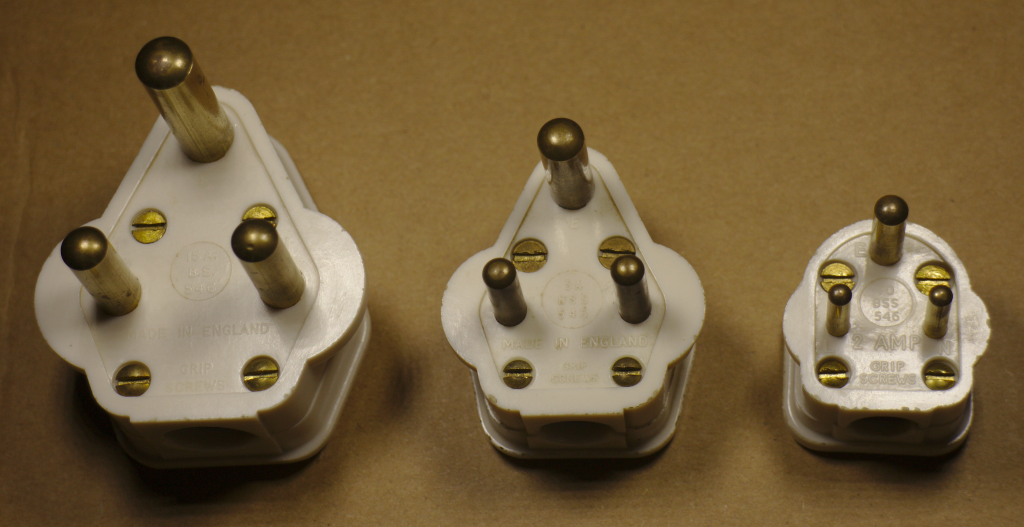

By 1934, regulations appeared requiring plugs and sockets to include an earthing prong, which eventually gave birth to a three, cylindrical-pronged plug: the BS 546.

BS 546 plugs

The BS 546 was different from the modern G-Type as they didn’t contain a fuse and were available in five different sizes depending on the needs of the appliance, from small 2 ampere plugs for low-power appliances to a larger 30 ampere version for industrial machinery. The different sizes and spacing of the prongs prevented low-power devices accidentally being plugged into high-power outlets.

Any chance of globally standardising plugs was doomed from the beginning, as different companies in different countries all began developing their own plugs for their products as electricity rapidly gained uptake.

Some attempts were made by the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) to standardise plugs globally but the Second World War put a stop to any progress.

Electricity for the people

Great Britain emerged from the Second World War with its national grid standing strong. The challenge now was to make electricity not just the power source of factories and wealthy people’s homes, but something available for everyone in the wave of new post-war construction.

Other countries, not seeing as much damage to their housing stock as the UK, did not have the same opportunity to rethink domestic electricity to such an extent. Therefore, the Institution of Electrical Engineers (IEE) assembled a 20-person committee to consider the electrical requirements of the country’s new homes.

Breaking new ground: Caroline Haslett

The sole woman on the committee, Caroline Haslett, had been breaking new ground for female engineers since before World War One. In her career she worked with turbine inventor Charles Parsons and his wife (an engineer in her own right) and in 1932 became the first woman selected to join the IEE. Her passion for electricity went so far as for her will to request she be cremated via electricity.

She had long believed in the potential for domestic electricity to improve women’s lives by freeing them from the drudgery of pre-electric domestic chores, from handwashing clothes to cooking on coal-fuelled stoves. This included ensuring electricity was safe for the people using electricity around the home which in the 1940s was primarily women, who also did the vast majority of childcare.

Haslett’s drive to make electricity safe in the home was pivotal in shaping many of the IEE’s safety requirements for post-war domestic electricity, including what have become the country’s standard plugs and sockets.

There was another factor aside from safety at play. The material cost of the war meant copper, the main material used in electrical wiring, was in short supply, so the IEE came up with a new way of wiring homes that would in turn shape our plugs.

Shifting fuses to save copper

Before the war, British sockets were all separately wired back to a central fuse box. It made sense, because if something went wrong only the fuse connected to that socket would blow rather than the whole house.

However, to cut the amount of copper used the IEE instead proposed a clever workaround where the home’s electrical sockets are looped up in one Ring Circuit, with the fuses moved to the plugs themselves. So, if something went wrong in an appliance the fault would stop at the plug, where the fuse could easily be accessed and replaced. Lighting fixtures remained wired in a separate circuit from sockets as they require less current to operate.

Copper was short in supply during World War Two.

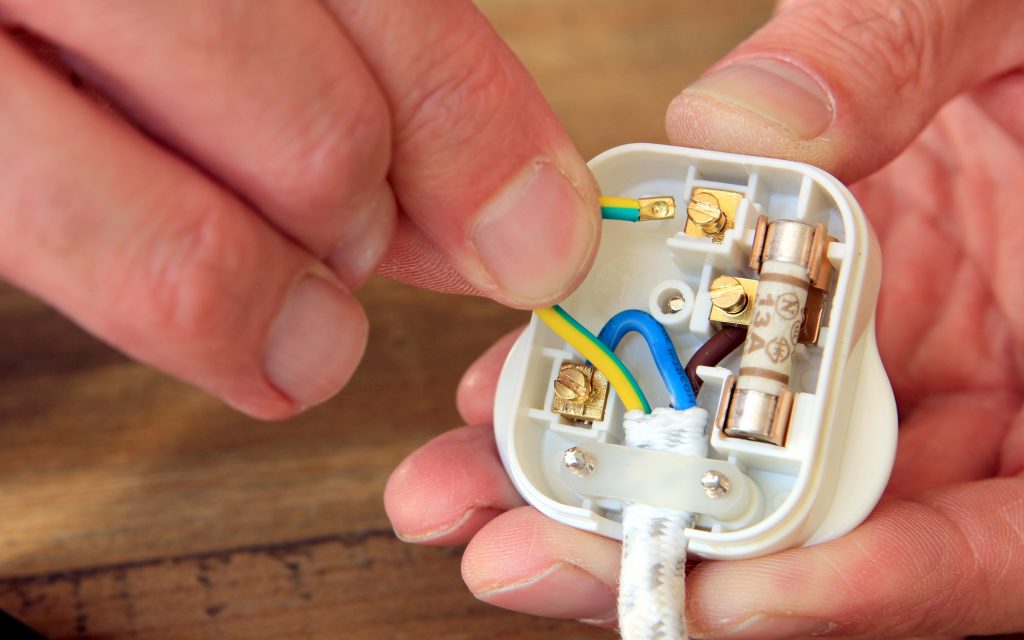

This hidden fuse, is a big differentiator from other plug types and adds to the G Type’s safety credentials. However, the IEE had to ensure people did not mistakenly insert older three-prong BS 546 plug styles without fuses into the sockets.

The answer was as simple as switching the socket holes from round to rectangle. It means the older round cylinder prongs wouldn’t fit into the slot designed for the rectangles found on plugs today.

The G Type plug might seem cumbersome compared to the European or US models, but in the 70-plus years since its introduction its three prongs and in-built fuse, has proved an enduring design that can power new devices and smart technology, while remaining one of the safest plugs in the world.