When making a cup of tea, it’s unlikely you consider the industrial equipment kicked into action the moment you switch on your kettle. And of all of the activity going on behind the scenes, it’s even more unlikely you think about a 1.2-tonne steel ball.

But without a number of 1.2-tonne balls and the electricity they help generate, your kettle would be nothing more than a fancy jug.

How do giant balls help to generate power?

The answer lies in the way fuels like coal and compressed wood pellets are used to power boilers and generate electricity. Drax started its life as a coal power station, but today it is in the process of upgrading to run on biomass. Progress has already been made – three of the station’s six units already run on compressed wood pellets, Drax’s biomass fuel, generating around 20% of the UK’s renewable electricity.

To generate enough power to supply 8% of the UK’s demand – as Drax does – a lot of fuel is needed. Hundreds of thousands of wood pellets are delivered to Drax every day, arriving on custom-built trains travelling from the Ports of Tyne, Hull, Immingham and Liverpool.

The pellets pass through a system of conveyor belts until they arrive at one of four massive conical storage domes, located on site in Yorkshire. Before the wood pellets can be converted into fuel, they need to be crushed: this is where the balls come into play.

The pulveriser

The wood pellets used at Drax are compressed and dried wood that is formed into small capsules the size of a child’s crayon. But, like with coal, to get the best results in the power station’s huge boilers, the material needs to be turned into a very fine powder in pulverising mills. When very fine, the fuel burns as efficiently and as quickly as a gas.

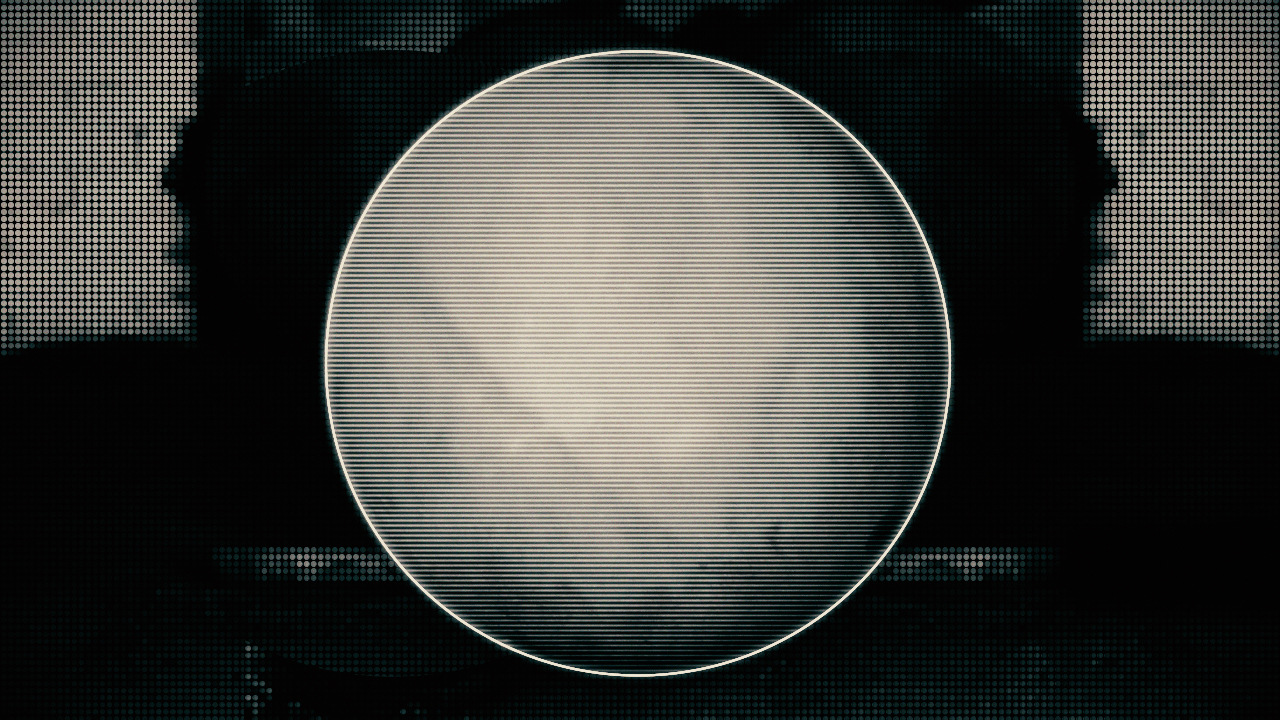

Inside each mill are 10 giant steel balls that grind down either the wood pellets or coal. Each ball is three quarters of a metre in size, made of hollow cast steel alloy and weighs roughly 1.2 tonnes – equivalent in weight to British-made Jaguar XE mid-sized saloon car or an entire football team.

And to make sure that each one is up to the task of extreme pulverisation, they need to be hard. Each one is heat treated during manufacture to make sure they’re up robust enough to consistently crush raw fuel.

The benefit of this durability is that they can readily pulverise fuel to feed Drax boilers, to power kettles across the country – a big responsibility for a big ball.