Electricity is such a universal and accepted part of our lives it’s become something we take for granted. Rarely do we stop to consider the path it took to become ubiquitous, and yet through the course of its history there have been several eureka moments and breakthrough inventions that have shaped our modern lives. Here are some of the defining moments in the development of electricity and power.

2750 BC – Electricity first recorded in the form of electric fish

Ancient Egyptians referred to electric catfish as the ‘thunderers of the Nile’, and were fascinated by these creatures. It led to a near millennia of wonder and intrigue, including conducting and documenting crude experiments, such as touching the fish with an iron rod to cause electric shocks.

500 BC – The discovery of static electricity

Around 500 BC Thales of Miletus discovered that static electricity could be made by rubbing lightweight objects such as fur or feathers on amber. This static effect remained unknown for almost 2,000 years until around 1600 AD, when William Gilbert discovered static electricity in earnest.

1600 AD – The origins of the word ‘electricity’

The Latin word ‘electricus’, which translates to ‘of amber’ was used by the English physician, William Gilbert to describe the force exerted when items are rubbed together. A few years later, English scientist Thomas Browne translated this into ‘electricity’ in his written investigations in the field.

1751 – Benjamin Franklin’s ‘Experiments and Observations on Electricity’

This book of Benjamin Franklin’s discoveries made about the behaviour of electricity was published in 1751. The publication and translation of American founding father, scientist and inventor’s letters would provide the basis for all further electricity experimentation. It also introduced a host of new terms to the field including positive, negative, charge, battery and electric shock.

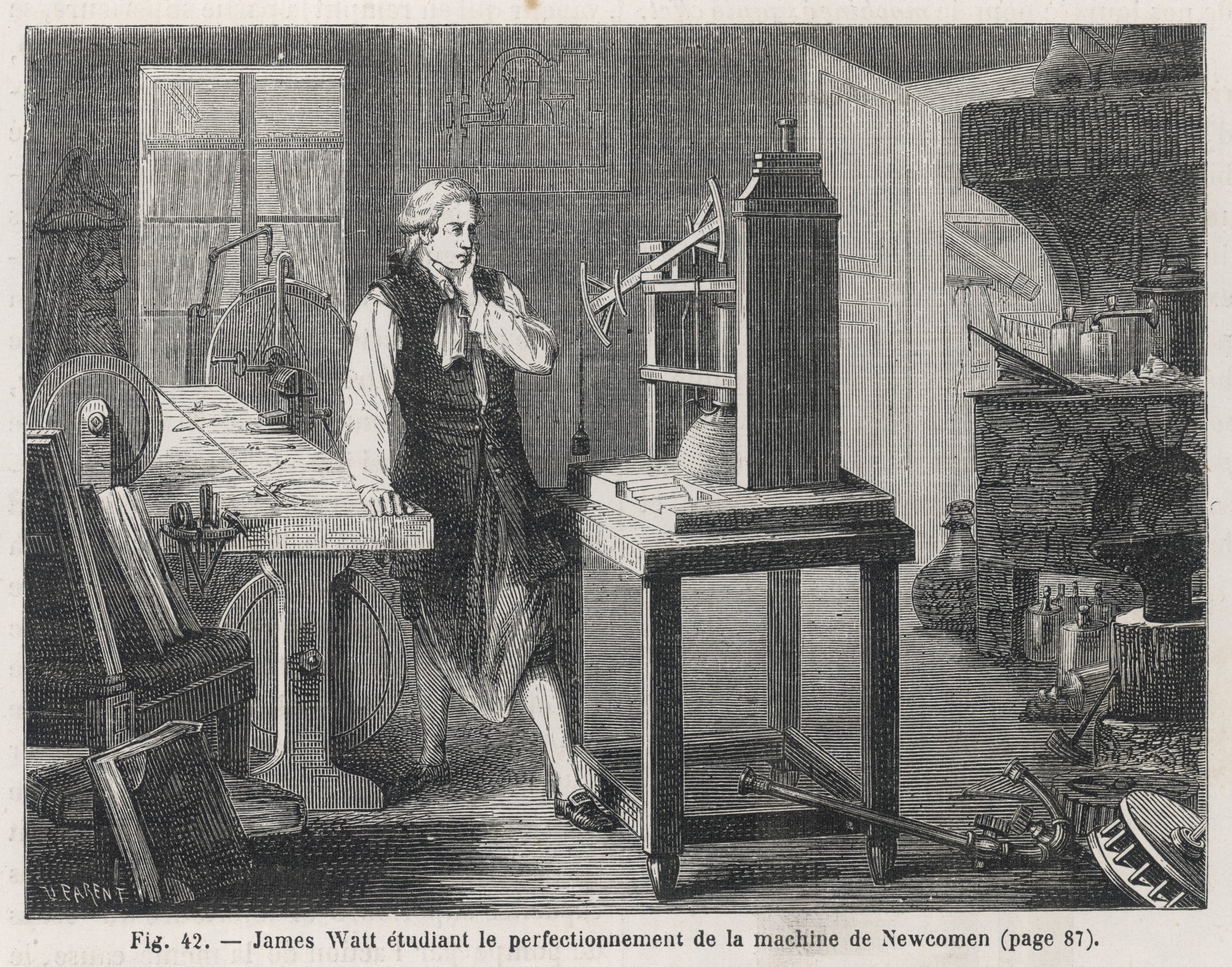

1765 – James Watt transforms the Industrial Revolution

Watt studies Newcomen’s engine

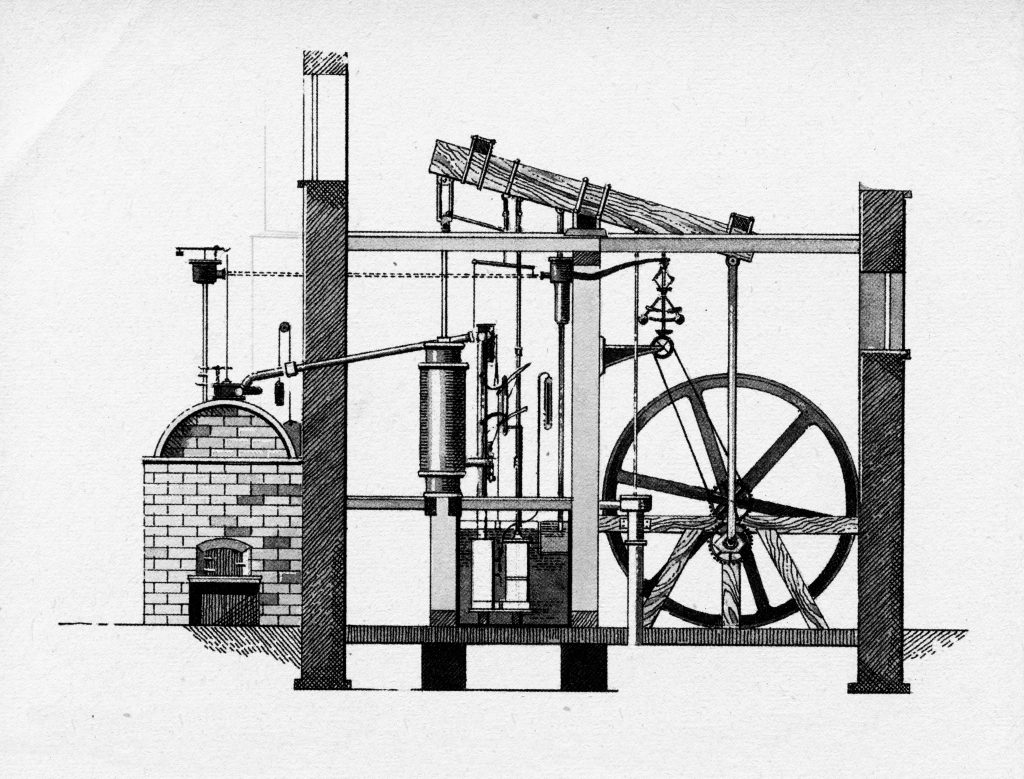

James Watt transformed the Industrial Revolution with the invention of a modified Newcome engine, now known as the Watt steam engine. Machines no longer had to rely on the sometimes-temperamental wind, water or manpower – instead steam from boiling water could drive the pistons back and forth. Although Watt’s engine didn’t generate electricity, it created a foundation that would eventually lead to the steam turbine – still the basis of much of the globe’s electricity generation today.

James Watt’s steam engine

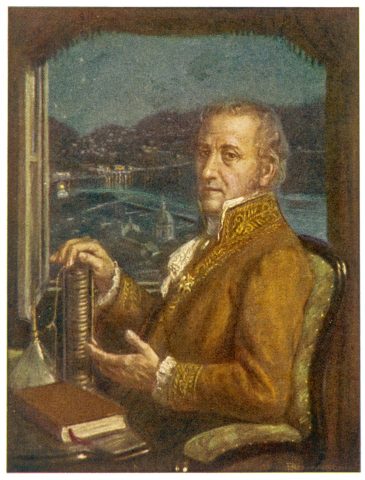

Alessandro Volta

1800 – Volta’s first true battery

Documented records of battery-like objects date back to 250 BC, but the first true battery was invented by Italian scientist Alessandro Volta in 1800. Volta realised that a current was created when zinc and silver were immersed in an electrolyte – the principal on which chemical batteries are still based today.

1800s – The first electrical cars

Breakthroughs in electric motors and batteries in the early 1800s led to experimentation with electrically powered vehicles. The British inventor Robert Anderson is often credited with developing the first crude electric carriage at the beginning of the 19th century, but it would not be until 1890 that American chemist William Morrison would invent the first practical electric car (though it closer resembled a motorised wagon), boasting a top speed of 14 miles per hour.

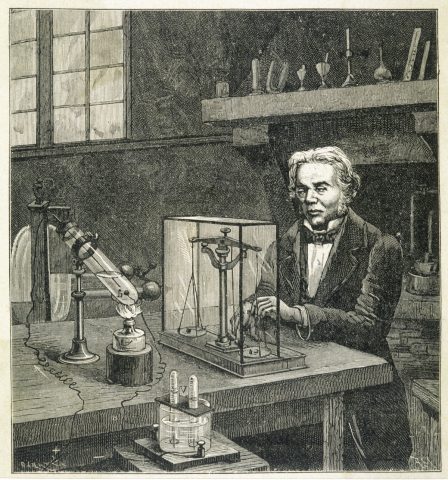

Michael Faraday

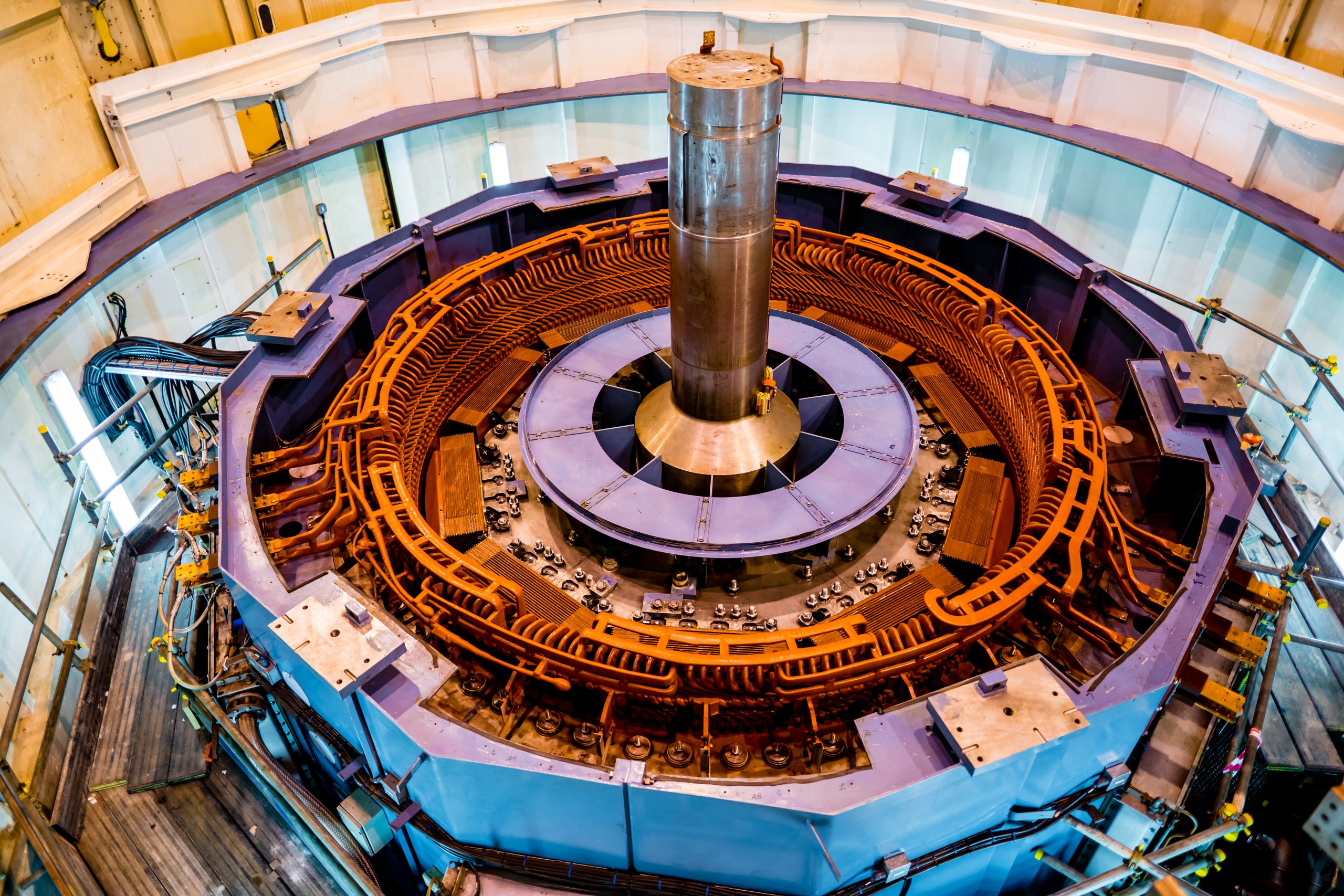

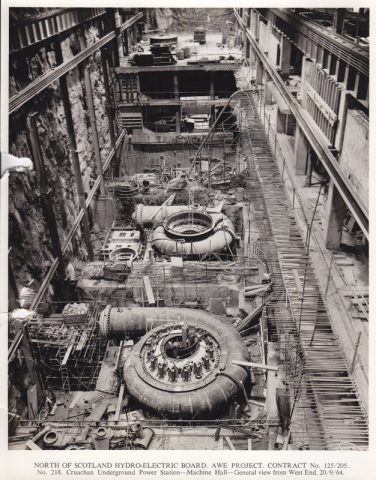

1831 – Michael Faraday’s electric dynamo

Faraday’s invention of the electric dynamo power generator set the precedent for electricity generation for centuries to come. His invention converted motive (or mechanical) power – such as steam, gas, water and wind turbines – into electromagnetic power at a low voltage. Although rudimentary, it was a breakthrough in generating consistent, continuous electricity, and opened the door for the likes of Thomas Edison and Joseph Swan, whose subsequent discoveries would make large-scale electricity generation feasible.

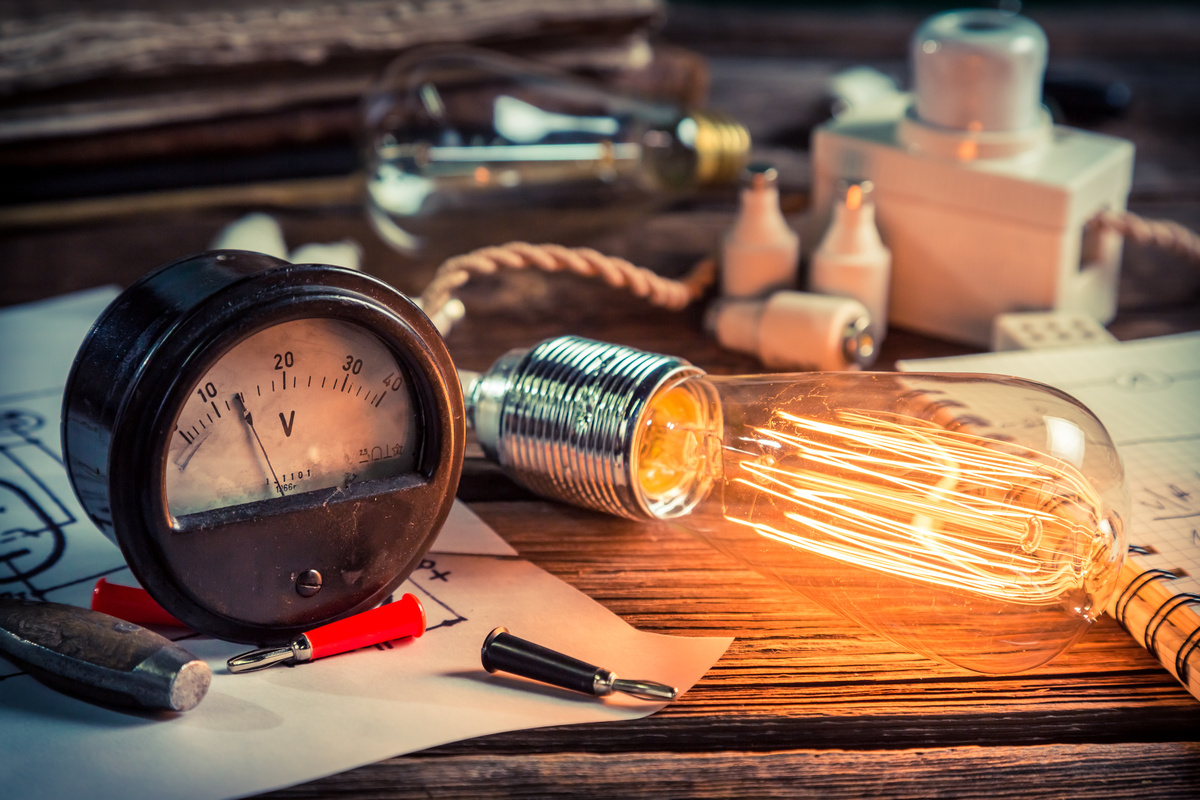

1879 – Lighting becomes practical and inexpensive

Thomas Edison patented the first practical and accessible incandescent light bulb, using a carbonised bamboo filament which could burn for more than 1,200 hours. Edison made the first public demonstration of his incandescent lightbulb on 31st December 1879 where he stated that, “electricity would be so cheap that only the rich would burn candles.” Although he was not the only inventor to experiment with incandescent light, his was the most enduring and practical. He would soon go on to develop not only the bulb, but an entire electrical lighting system.

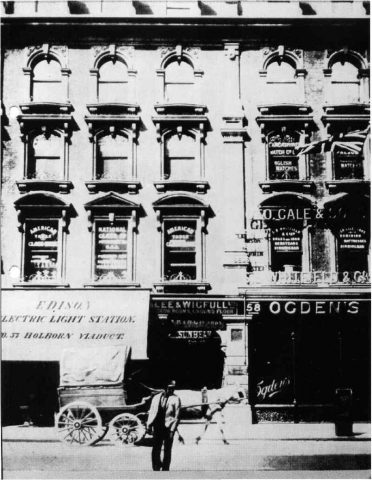

Holborn Viaduct power station via Wikimedia

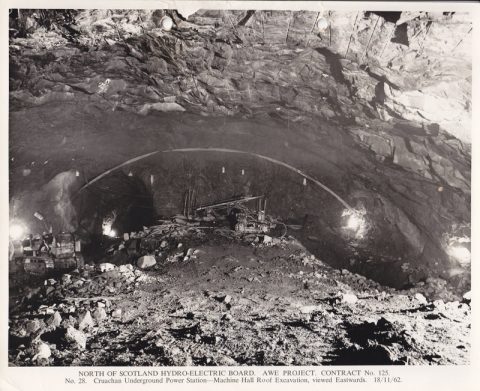

1882 – The world’s first public power station opens

Holborn Viaduct power station, also known as the Edison Electric Light Station, burnt coal to drive a steam turbine and generate electricity. The power was used for Holborn’s newly electrified streetlighting, an idea which would quickly spread around London.

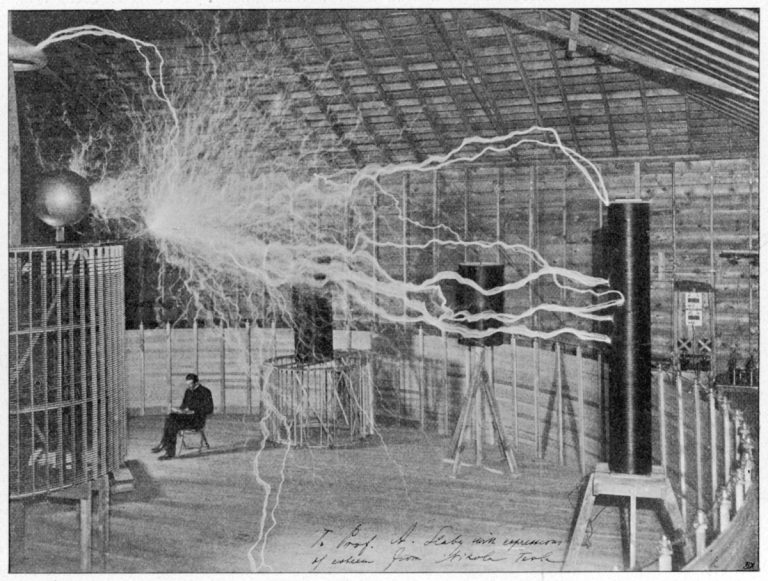

1880s – Tesla and Edison’s current war

Nikola Tesla and Thomas Edison waged what came to be known as the current war in 1880s America. Tesla was determined to prove that alternating current (AC) – as is generated at power stations – was safe for domestic use, going against the Edison Group’s opinion that a direct current (DC) – as delivered from a battery – was safer and more reliable.

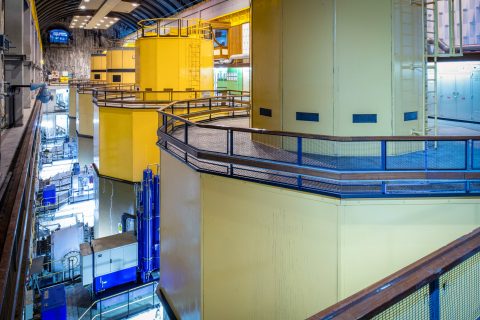

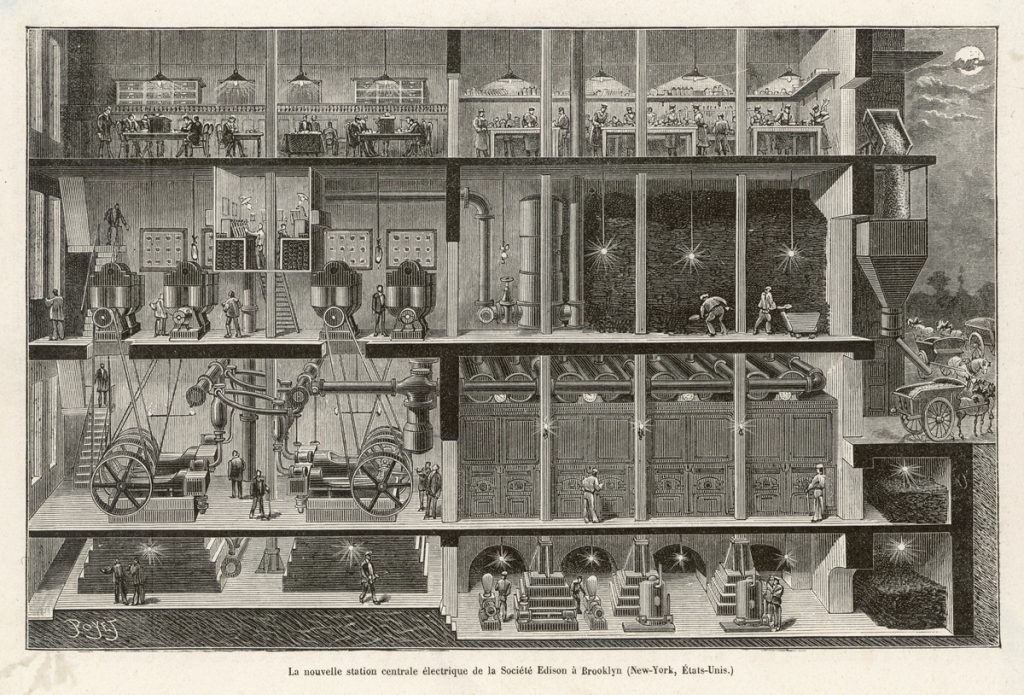

Inside an Edison power station in New York

The conflict led to years of risky demonstrations and experiments, including one where Tesla electrocuted himself in front of an audience to prove he would not be harmed. The war continued as they fought over the future of electric power generation until eventually AC won.

Nikola Tesla

1901 – Great Britain’s first industrial power station opens

Before Charles Mertz and William McLellan of Merz & McLellan built the Neptune Bank Power Station in Tyneside in 1901, individual factories were powered by private generators. By contrast, the Neptune Bank Power Station could supply reliable, cheap power to multiple factories that were connected through high-voltage transmission lines. This was the beginning of Britain’s national grid system.

1990s – The first mass market electrical vehicle (EV)

Concepts for electric cars had been around for a century, however, the General Motors EV1 was the first model to be mass produced by a major car brand – made possible with the breakthrough invention of the rechargeable battery. However, this EV1 model could not be purchased, only directly leased on a monthly contract. Because of this, its expensive build, and relatively small customer following, the model only lasted six years before General Motors crushed the majority of their cars.

2018 – Renewable generation accounts for a third of global power capacity

The International Renewable Energy Agency’s (IRENA) 2018 annual statistics revealed that renewable energy accounted for a third of global power capacity in 2018. Globally, total renewable electricity generation capacity reached 2,351 GW at the end of 2018, with hydropower accounting for almost half of that total, while wind and solar energy accounted for most of the remainder.