- Voluntary reporting for Drax’s EU Taxonomy alignment shows why we must keep leading on sustainable finance

- Our upgraded CDP scores further underline our credentials for best practice in both strategy and action

Sustainability shapes how we operate at Drax. It provides our stakeholders with the trust they need as we demonstrate how we strive to provide secure, renewable energy to millions of homes and businesses, in a responsible way.

That is why we are pleased to hit another significant milestone in our ongoing sustainability journey, with the release of our first ever EU Taxonomy Report.

The report reflects our deep commitment to sustainability and highlights our continued work towards aligning ourselves with the European Union’s sustainability goals. In terms of results, the report shows that 71% of Drax’s revenue qualifies as eligible and aligned with the Taxonomy, with 99% of that aligned revenue meeting sustainability principles.

But what is it? EU Taxonomy is a classification system that was created by the European Commission, to define which economic activities contribute to environmental sustainability. It serves as a core part of the EU’s sustainable finance framework, guiding investment flows towards activities that align with the EU’s Green Deal and its broader climate goals.

It’s essentially a roadmap for companies and investors to understand what qualifies as environmentally sustainable. For businesses like Drax, aligning with the EU Taxonomy is essential, as it reinforces our ambition to help tackle climate change while maintaining strong financial performance.

So, why is the EU Taxonomy so important in the context of Drax’s sustainability journey? It’s because the system establishes clear guidelines and benchmarks aimed at ensuring that investment is directed towards activities that contribute meaningfully to environmental sustainability.

It plays a crucial role in accelerating the transition to a green economy and helps companies like Drax with their ambitions to meet their global sustainability targets. By aiming to align what we do with the EU Taxonomy, we aim to ensure that our operations, revenue generation, and financial models support these crucial climate objectives.

The results of our first EU Taxonomy Report demonstrate how far we’ve come in our sustainability efforts. The headline figure that 99% of our eligible revenue meets the sustainability criteria is a source of pride. This is a strong affirmation of our long-term dedication to environmental stewardship and is a significant achievement.

Compared to the broader business landscape, our results are an extraordinary achievement. A 2024 report from EY, that used a sample of 307 European companies non-financial disclosures, showed that the average EU Taxonomy alignment for turnover was 10% across all sectors, with the energy and power sector rising to 37%. For Drax, this rises even further to 71%, positioning us as a leader in taxonomy-aligned sustainability principles.

The reason for this alignment is simple: Drax has made intentional and strategic decisions over the years to transition our business towards renewable energy, with the most notable being the transition from coal to biomass at Drax Power Station.

However, achieving alignment with the EU Taxonomy goes beyond just ticking the necessary boxes. We’re focused on aiming to exceed the minimum standards set out by the taxonomy. The fact that 71% of our revenue is fully aligned with the EU Taxonomy speaks to the forward-thinking strategies that we have put in place.

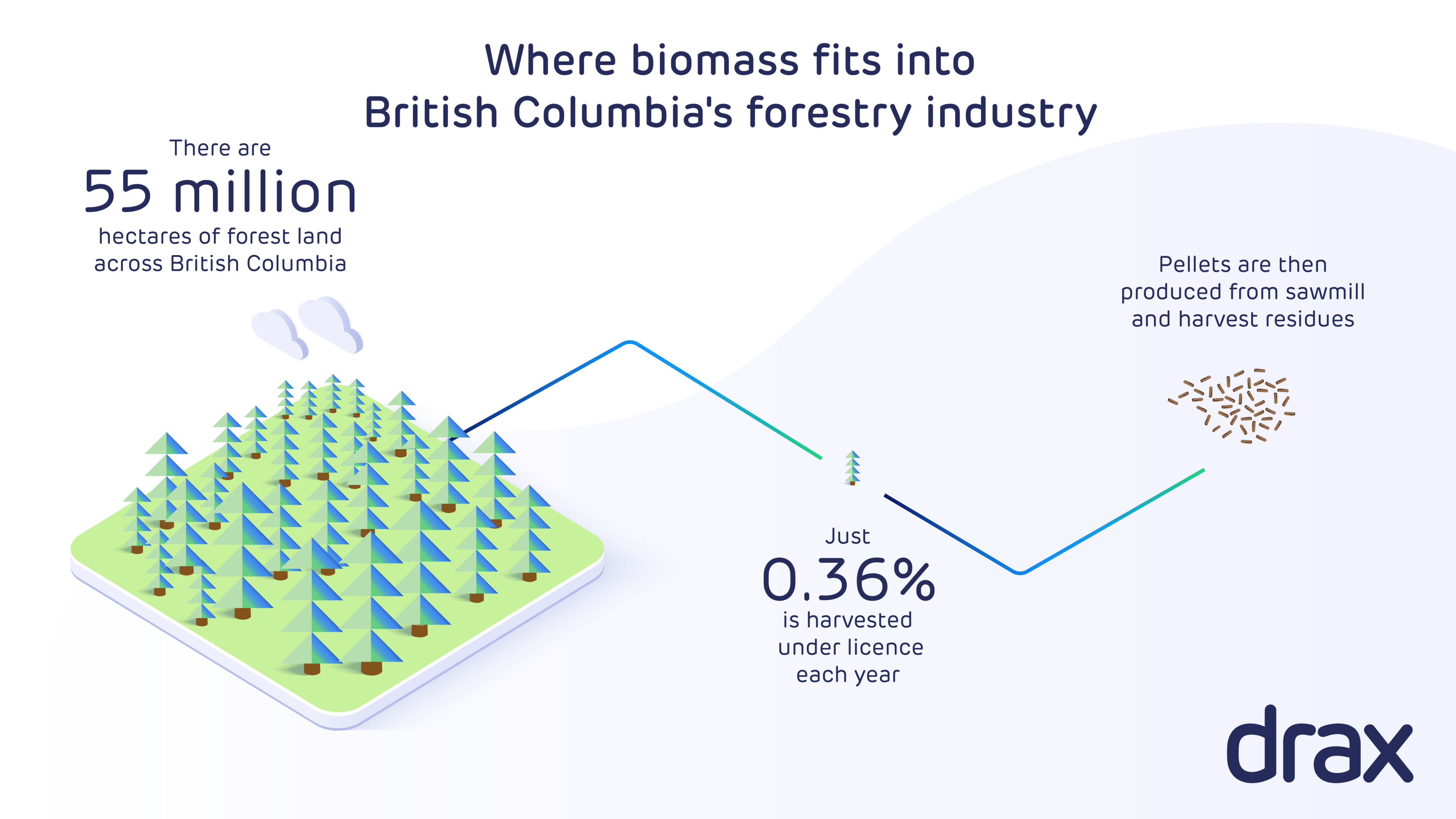

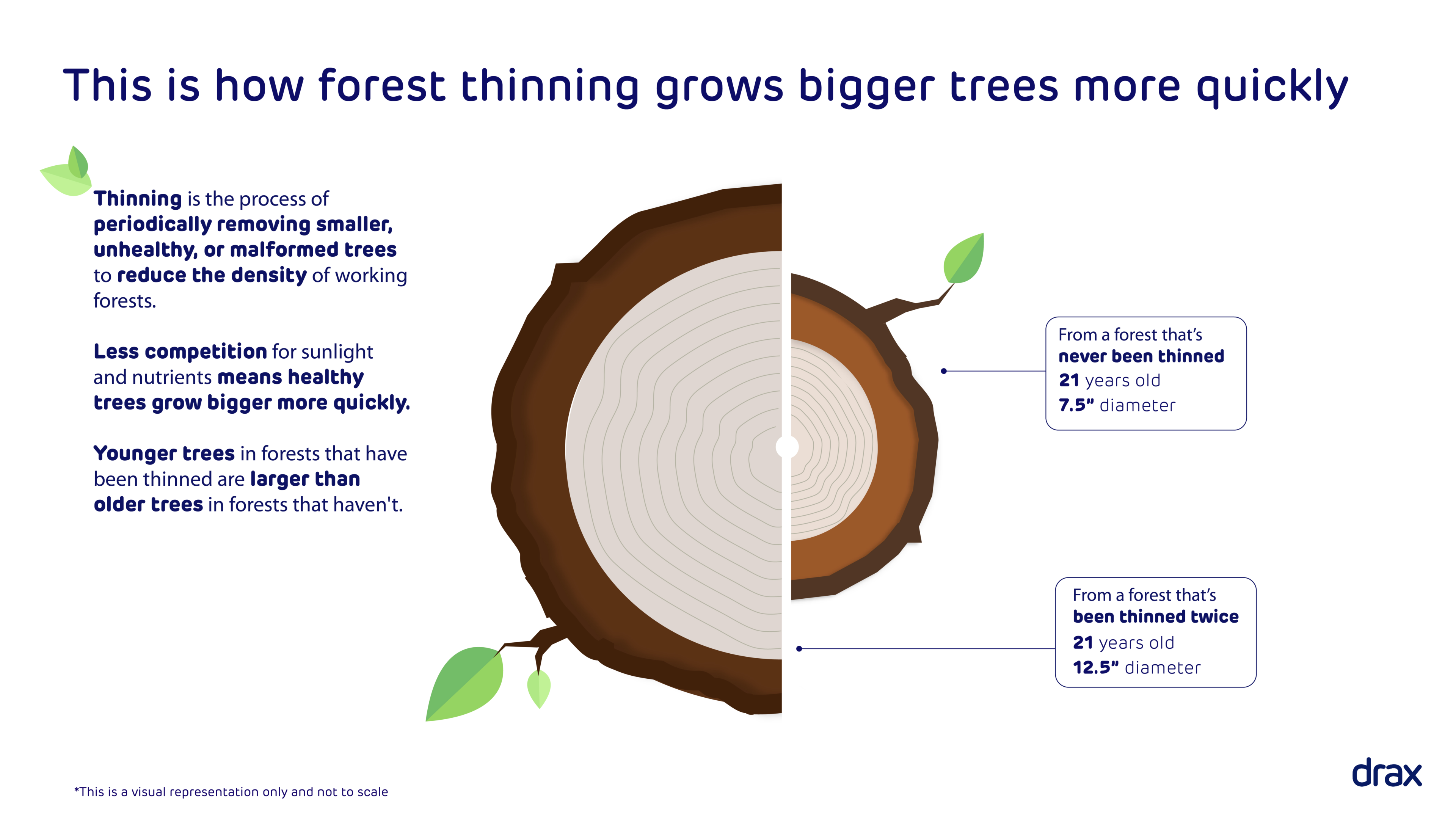

One of the key pillars of sustainability at Drax is our focus on forestry, specifically how we manage and source biomass. Forests are a crucial component of the global carbon cycle. As part of our commitment to achieve net zero by the end of 2040 across our value chain, we endeavour to source our biomass from sustainably managed forests and must be mindful of the impact our activities have on biodiversity, carbon sequestration, communities, and forest health.

This is where the importance of our CDP (Carbon Disclosure Project) scores come in and these act like a snapshot of a company’s performance on environmental action. Their annual reports provide valuable insights into a company’s efforts to reduce emissions and manage natural resources responsibly, using voluntarily disclosed data to provide a score based upon three main critical areas: greenhouse gas emissions, water management, and deforestation.

We have worked hard on these areas, to demonstrate our dedication and progress towards climate action to our investors and other stakeholders. We have maintained our A- CDP climate score and alongside this our CDP Forests score was upgraded to A-. For the first time this positions Drax in the highest ‘leadership’ banding of CDP scores, recognising best practice for both strategy and action, and ranking Drax in the leading group of FTSE businesses.

The upgraded CDP score for forestry reflects our ongoing efforts to aim to ensure that our biomass sourcing practices do not contribute to deforestation or degradation of ecosystems. By sourcing from responsibly managed forests, we aim to ensure that our biomass is part of a sustainable, circular process where forest health is maintained and enhanced.

We recognise that both environmental sustainability as measured by the EU Taxonomy and our evolving CDP scores will require consistent work to maintain and improve. Alongside this we have developed a new sustainability framework, in consultation with a variety of different groups including representatives from the scientific community, academics, employees, investors and environmental NGOs.

But this holistic approach must be seen as the starting point of a journey. With the climate crisis becoming an even bigger threat to our planet, we must redouble our efforts. That means open and frank conversations with internal and external stakeholders where possible and concerted efforts to decarbonise our supply chain. It also means continuing to prioritise the rigorous standards of best practice measured by mechanisms such as EU taxonomy and CDP ratings. These pillars will be the key to proving that Drax can keep the lights on for millions of people using sustainable biomass generation, responsibly.

Scope Two emissions are those which come from the generation of energy an organisation uses. These can include emissions form electricity, steam, heating, and cooling.

Scope Two emissions are those which come from the generation of energy an organisation uses. These can include emissions form electricity, steam, heating, and cooling.