It’s 1990 and Chris Waddle, England midfielder, steps up to the penalty spot. The 60,000 people in Turin’s Stadio delle Alpi watching him and the fate of England football go silent.

He takes a breath and fires a shot at Bodo Illgner, the German goalkeeper. It careers over the crossbar and misses – England are out of the World Cup. The now famous image of Paul Gascoigne crying into his shirt is beamed across millions of UK television screens.

There’s a shuffling on the sofas in front of those TVs as the population gets up to make a cup of tea, get a drink or turn on the oven. Millions of kettles, lights and fridges are powered up as the country collectively despairs. The demand for electricity across the country soars.

This is what’s called a ‘TV pickup’ – the moment during a popular television event when there’s a break and viewers unwittingly cause a huge surge of demand from the National Grid.

It’s these moments that have caused some of the biggest spikes in UK electricity demand. Here we look at what’s caused them:

One:

What? Football World Cup Semi Final: England v West Germany

When? Wednesday, 4 July 1990

Electricity demand: 2,800MW – equivalent to 1,120,000 kettles (based on 1MW = 400 kettles), or 4.3 Drax-sized generation units (there are six 645MW units at Drax)

After that fateful penalty miss the population made for the kitchen. The match was watched by an estimated 26 million people in the UK, and when full time was called they caused a 2,800MW surge in electricity demand.

Two:

What? The Thorn Birds

When? 22 January 1984

Electricity demand: 2,600MW – 1,040,000 kettles – 4 Drax units

A sleeper hit, The Thorn Birds was a one-off American mini-series about a fictional sheep station in the Australian outback. Based on the novel of the same name, it was broadcast in the UK following building up a huge following in the US when it was aired in 1983. By the time it arrived on UK shores there was clearly enough of that excitement to create a surge of electricity demand – one of the largest in UK TV history.

Three:

What? Football World Cup Quarter Final: England v Brazil

When? Friday, 21 June 2002

Electricity demand: 2,570MW – 1,028,000 kettles – 4 Drax units

Broadcast early on a Wednesday morning in the UK due to time differences with South Korea, where the game was played, the match saw England put up a solid fight against overall tournament winners Brazil. A goal from Michael Owen provided early hope and at half time TV viewers left their screens to cause a huge 2,570MW spike in demand. By the time the game had reached its conclusion, Brazil had won thanks to a chipped Ronaldinho free kick that fooled England keeper David Seaman and those viewers who had lasted the duration caused a slightly smaller 2,300MW surge.

Four:

Four:

What? Eastenders: Lisa admits shooting Phil

When? Thursday, 5 April 2001

Electricity demand: 2,290MW – 916,000 kettles – 3.5 Drax units

In one of the most dramatic plot developments in UK TV history, Lisa Shaw, played by actress Lucy Benjamin, admitted to shooting her former boyfriend, Phil Mitchell. An estimated 22 million viewers turned on to see the dramatic reveal. When it was all over they caused a surge of 2,290MW, more than five times the normal pickup of 400MW seen at the end of an average Eastenders episode.

Five:

What? The Darling Buds of May

When? Sunday, 12 May 1991

Electricity demand: 2,200MW – 880,000 kettles – 3.4 Drax units

One of the more wholesome entries to the list, this British comedy drama racked up a huge following during its 20-episode run from 1991 to 1993. The peak was early in the first season, when the third ever episode saw the Larkin family take an unhappy holiday to Brittany. The family’s escapades drew a large audience and prompted a surge equivalent to 880,000 kettles being switched on at the same time.

Six:

What? Rugby World Cup Final: England v Australia

When? Saturday, 22 November 2003

Electricity demand: 2,110MW – 844,000 kettles – 3.3 Drax units

A unique sporting entry to the list as England ended as winners. More than 12 million people watched England beat Australia, with the largest electricity demand coming at half time and not at full time, when audiences were presumably still celebrating Jonny Wilkinson’s last minute drop goal.

Seven:

What? European Football Championship 2020 final: England vs Italy

When? Sunday, 11 July 2021

Electricity demand: 1,800MW – 720,000 kettles – 2.8 Drax units

The most recent heartbreaker for England fans, the match came as COVID-19 restrictions were only beginning to lift around the UK. The team, led by Gareth Southgate, conquered old foes Germany on their way to a final in Wembley, only to lose to Italy on penalties.

The sense of disappointment was almost palpable in the energy demand, peaking at 1,800MW at half-time, when England went into the changing rooms one-nil up. Demand then surged again to 1,200MW at the end of the 90-minute stalemate, followed by a deflated 500MW at the end of the game. Had things gone differently, National Grid ESO was preparing for a peak of 2,000MW.

Eight:

What? The Royal Wedding – Prince William and Kate

When? Friday, 29 April 2011

Electricity demand: 1,600MW – 640,000 kettles – 2.5 Drax units

The biggest and most celebrated Royal Wedding in a generation, the marriage of Prince William and Kate Middleton attracted an audience of 24 million in the UK alone. Energy demand peaked at 1,600MW when the bride’s carriage procession returned to Buckingham Palace. This is the largest TV pickup in recent years, which hints at how changing viewer habits, on demand watching and smart TVs are changing the need for power and making TV pickups a rarer occurrence.

Nine:

What? Clap for carers

What? Clap for carers

When? Thursday, 16 April 2020

Electricity demand: 950MW – 320,000 kettles – 1.5 Drax units

COVID-19 and subsequent lockdowns had several interesting effects on the UK’s energy system. One feature was a return in regular demand spikes, with Thursday evenings’ Clap for Carers events prompting notable surges.

The gestures, held at 8pm on Thursdays between 26 March and 28 May 2020, saw millions across the UK stand outside their homes and clap in appreciation of emergency services workers. As people went back inside to put on kettles and turn on TVs electricity demand spiked. The particularly cloudy evening of 16 April saw demand reach 950MW as more people reached for light switches.

How do we deal with TV pickups?

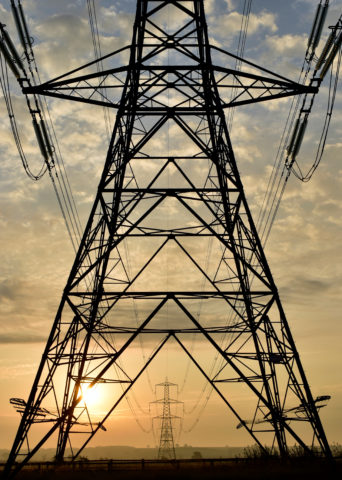

National grid electricty pylon at sunrise

Because the level of electricity needed to power the country can’t be stored, when there is a spike in demand it needs to be met quickly by a similar increase in real time generation.

To manage the supply and demand for events likely to cause electricity surges, the National Grid forecasts electricity need for large events like World Cups and major TV events.

The grid can then put contingency measures in place to manage the huge changes in demand in real time. It does this through a suite of tools called balancing mechanisms, which allows it to access sources of extra power in real-time.

The rise of more energy efficient home appliances and on-demand streaming means that the ‘shape’ of electricity demand has become flatter since the days when most of the country was tuned into the same must-see moments.

However, it’s still crucial for the grid to forecast periods of high demand, when it will keep the necessary power stations on reserve, ready to deliver additional electricity if needed.

If it wasn’t for this careful management of electricity by the grid and the power stations like Drax supplying it, that cup of tea next time England crash out of a major sporting event would not only be tainted with disappointment but cold, too.

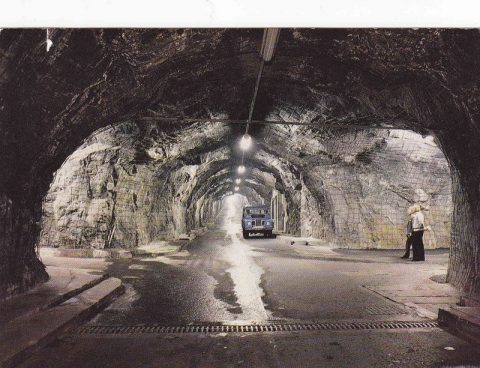

The access tunnel, cavern and the networks of passageways and chambers that make up the power station were all blasted and drilled by a workforce of 1,300 men in the

The access tunnel, cavern and the networks of passageways and chambers that make up the power station were all blasted and drilled by a workforce of 1,300 men in the  However, the reservoir also makes use of the aqueduct system made up of 19 kilometres of tunnels and pipes that covers 23 square kilometres of the surrounding landscape, diverting rainwater and streams into the reservoir. Calculating quite how much of the reservoir’s water comes from the surrounding area is difficult but estimates put it at around a quarter.

However, the reservoir also makes use of the aqueduct system made up of 19 kilometres of tunnels and pipes that covers 23 square kilometres of the surrounding landscape, diverting rainwater and streams into the reservoir. Calculating quite how much of the reservoir’s water comes from the surrounding area is difficult but estimates put it at around a quarter.

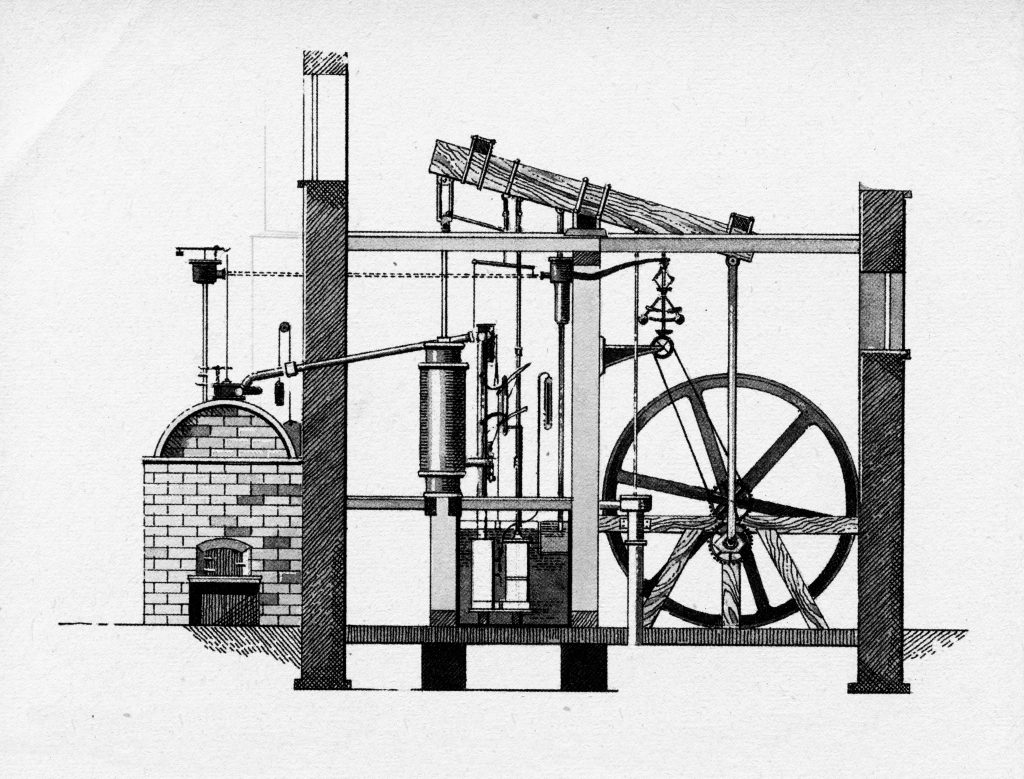

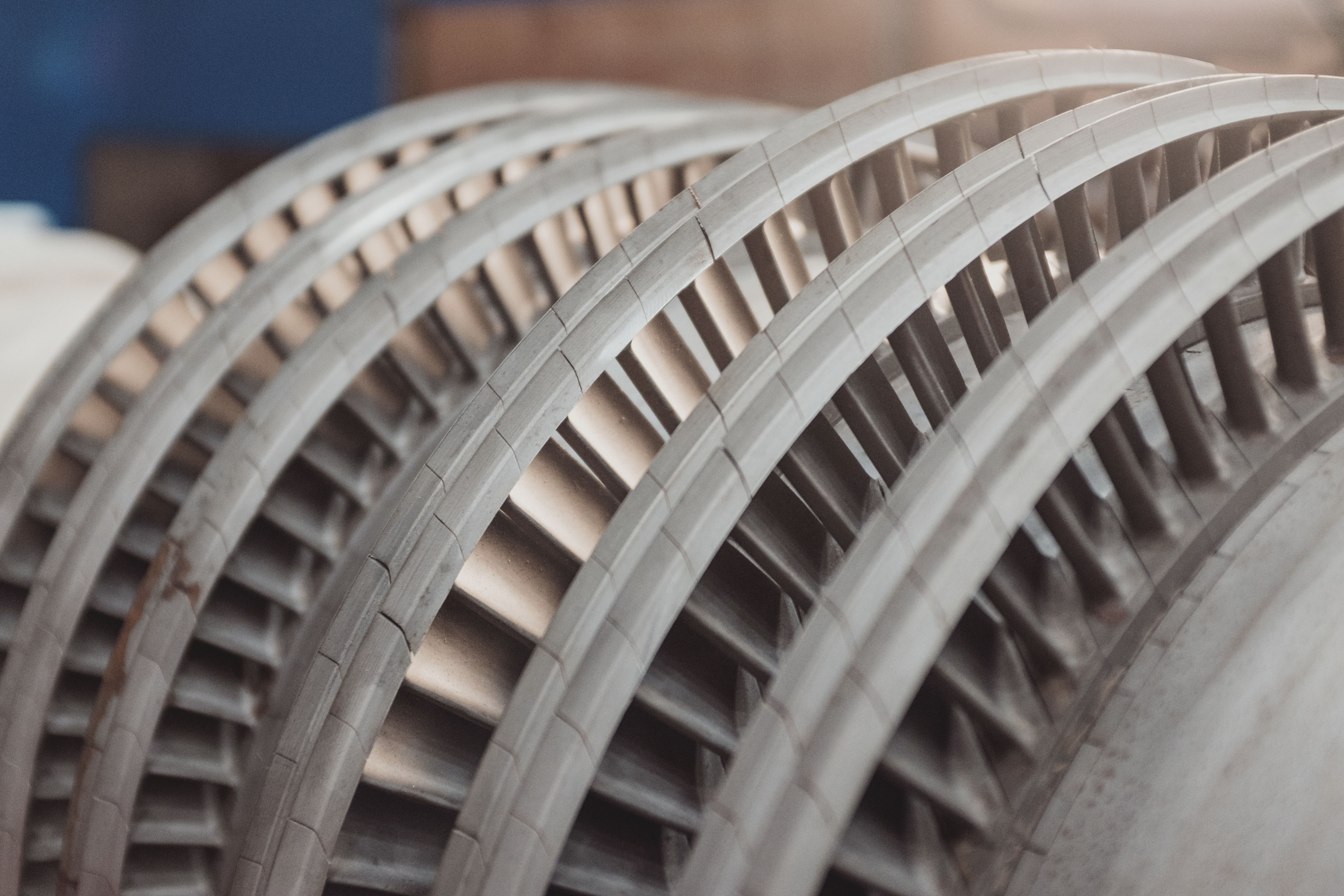

Steam engines and steam power was not a new concept when Parson began his explorations in the space. In fact, nor were steam turbines. Others had explored ways to use stream’s velocity to spin blades rather than using its pressure to pump pistons, in turn allowing rotors to spin at much greater speeds while requiring less raw fuel.

Steam engines and steam power was not a new concept when Parson began his explorations in the space. In fact, nor were steam turbines. Others had explored ways to use stream’s velocity to spin blades rather than using its pressure to pump pistons, in turn allowing rotors to spin at much greater speeds while requiring less raw fuel.