Over the past decade the United Kingdom has decarbonised significantly as coal power has been replaced by sources like biomass, wind and solar. Every year power generation emits fewer and fewer tonnes of carbon thanks to renewables and with the ban on the sale of new diesel and petrol cars coming in no later than 2040, roads and urban areas are about to get cleaner too.

However, there are still tough challenges ahead if the UK is to meet its target of carbon neutrality by 2050. Aviation, heavy industry, agriculture, shipping, power generation – some of the key activities of daily economic life – all remain reliant on fuels that emit carbon.

This is where Greenhouse Gas Removal (GGR) technologies have a big role to play. These can capture carbon dioxide (CO2) and other greenhouse gases from the atmosphere, and either store them or use them, helping the drive towards carbon neutrality.

While the idea of being able to capture carbon has been around for some time, the technology is fast catching up with the ambition. There now exist a number of credible solutions that allow for capturing emissions. The challenge, however, is putting in place the framework and policies needed to enable technologies to be implemented at scale.

Time is short. A recent report by Vivid Economics for the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) emphasised the need for government action now if we are to achieve the volume of carbon removal needed to achieve net zero emissions by 2050.

The tech to take emissions out of the atmosphere

The planet naturally absorbs CO2, forests absorb it as they grow, mangroves trap it in flooded soils, and oceans absorb it from the air. So, harnessing this power through planting, growing and actively managing forests is one natural method of GGR that can be easily implemented by policy.

Aerial view of mangrove forest and river on the Siargao island. Philippines.

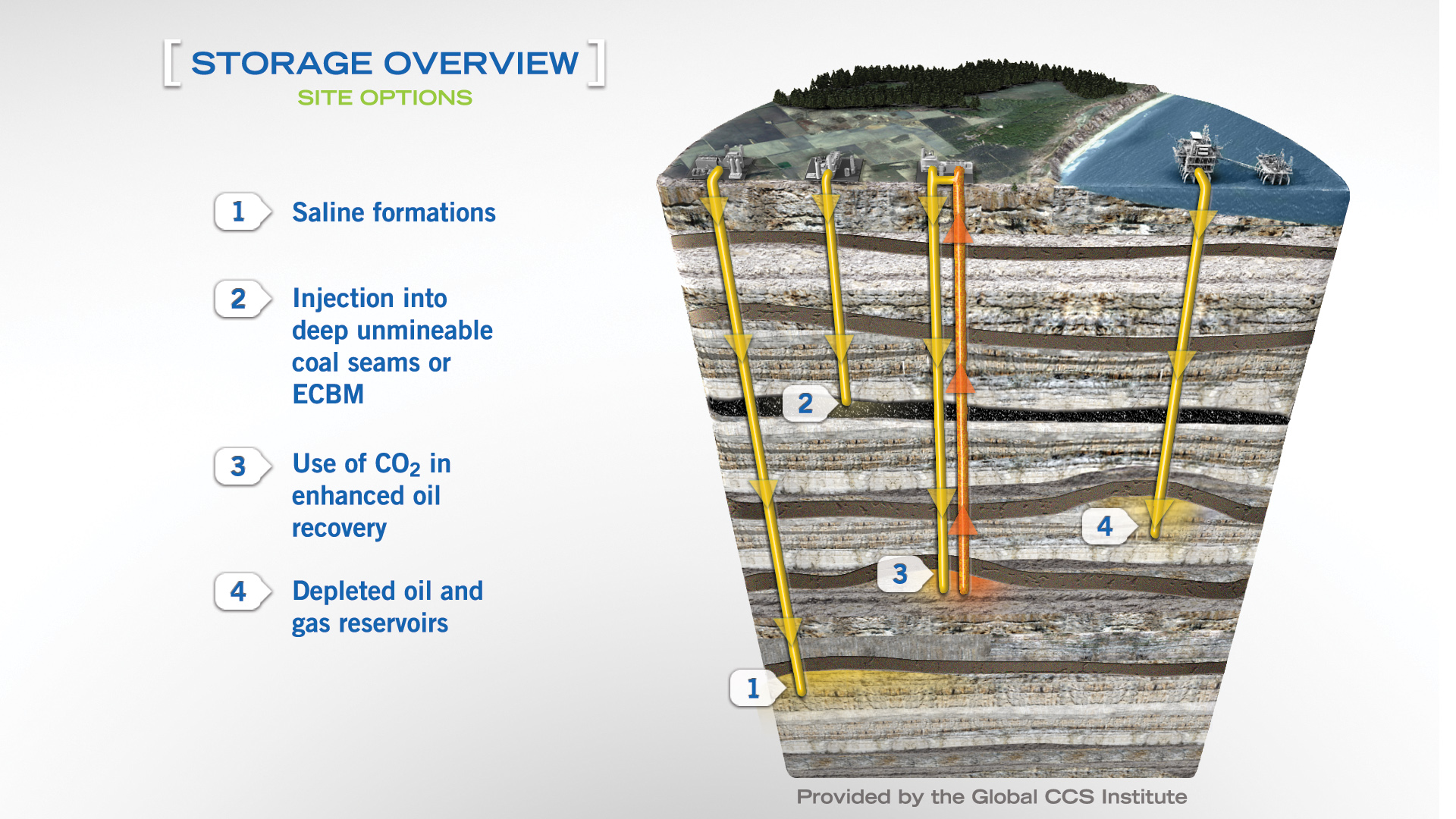

The idea of using technology to capture CO2 and prevent its release into the atmosphere has been around since the 1970s. It was first deployed successfully in enhanced oil recovery, when captured emissions are injected into underground oil reserves to help remove the oil from the ground.

Over time it’s been developed and is now in place in a number of fossil fuel power stations around the world, allowing them to cut emissions. However, by combining the same technology with renewable fuels like compressed biomass wood pellets, we can generate electricity that is carbon negative.

Each of these solutions operate in different ways, but all are important. Vivid Economics’ report emphasises that a range of different solutions will be required to reach a point where 130 million tonnes of CO2 (MtCO2) are being removed from the atmosphere in the UK annually by 2050.

However, investment and clear government planning and guidance will be crucial in enabling the growth of GRR. The report estimates large-scale GGR could cost around £13 billion per year by 2050 in the UK alone, a figure similar in size to current government support for renewables.

“If you went back 20-odd years, people were sceptical of the role of wind, solar and biomass and whether the technologies would ever get to a cost point where they could be viably deployed at scale,” explains Drax Policy Analyst Richard Gow.

“In the last few years we’ve seen enormous cost reductions in renewables and people are far more confident in investing in them – that has been driven by very good government policy.”

GGR needs the same clear long-term strategy to enable companies to make secure investments and innovate. But what shape should those policies take for them to be effective?

Options for policies

Perhaps the most straightforward route to enabling GGR is to build on existing policies. For example, there are existing tree planting schemes such as the Woodland Carbon Fund, Woodland Carbon Code and the Country Stewardship Scheme, all of which could receive greater regulatory support, or additional rules obliging emitters to invest in actively managed forests.

More technically complex solutions, like bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS) and direct air carbon capture and storage (DACCS), could be incentivised by alternative mechanisms in order to provide clarity on, and to stabilise, revenue streams. These are already used to support companies building low-carbon power generation such as through the Contracts for Difference scheme and have been effective in encouraging investment in projects with high upfront costs and long-payback periods.

Alternative options to support the roll-out of negative emissions technologies should also be considered. For example, the government could make it obligatory for companies that contribute to emissions, to pay for GGR to avoid increased burden on electricity consumers.

In such a scenario, fossil fuel suppliers would be required to offset the emissions of their products by buying negative emissions certificates from GGR providers. As a result, the price of fossil fuels for users would likely rise to cover this expense and the costs would then be shared across the supply chain rather than just a single party.

Another approach that passes the costs of GGR deployment on to emitters is using emissions taxes to fund tax credits for GGR providers.

Making these tax credits tradable would also mean any large tax-paying company, such as a supermarket or bank, could buy tax credits from GGR providers. This approach would come at no cost to government as sales of the tax credits would be funded by an emissions tax and would offer revenue to GGR providers.

The challenge with tax credits, however, is they are vulnerable to changes in government. An alternative is to offer direct grants and long-term contracts with GGR providers which would ensure funding for projects that transcends changes in Parliament. They could, however, prove costly for government.

Whatever policy pathway the government may choose to follow, there are underlying foundations needed to support effective GGR deployment.

Making policies work

There are still many unknown factors in GGR deployment, such as the precise volume that will be needed to counter hard-to-abate emissions. This means all policy must be flexible to allow for future changes, and the individual requirements of different regions (forest-based solutions might suit some regions, DACCS might be better in others).

Underlying the strength of any of these policies, is the need for accurate carbon accounting. Understanding how much emissions are removed from the atmosphere by each technology will be key to reaching a true net zero status and giving credibility to certificates and tax credits.

Pearl River Nursery, Mississippi

Proper accounting of different technologies’ impact will also be crucial in delivering innovation grants. These can come through the UK’s existing innovation structure and will be fundamental to jumpstarting the pilot programmes needed to test the viability of GGR approaches before commercialisation.

Different approaches to GGR have different levels of effectiveness as well as different costs. BECCS, for example, serves two purposes in both generating low-carbon power and capturing emissions – resulting in overall negative emissions across the supply chain.

“It’s important to account for the full value chain of BECCS,” explains Gow. “Therefore, it should be rewarded through two mechanisms: a CfD for the clean electricity produced and an incentive for the negative emissions. A double policy here is important because you are providing two products which benefit different sectors of the economy, one benefits power consumers and the other provides a service to society and the environment as a whole, and cost should be apportioned as such.

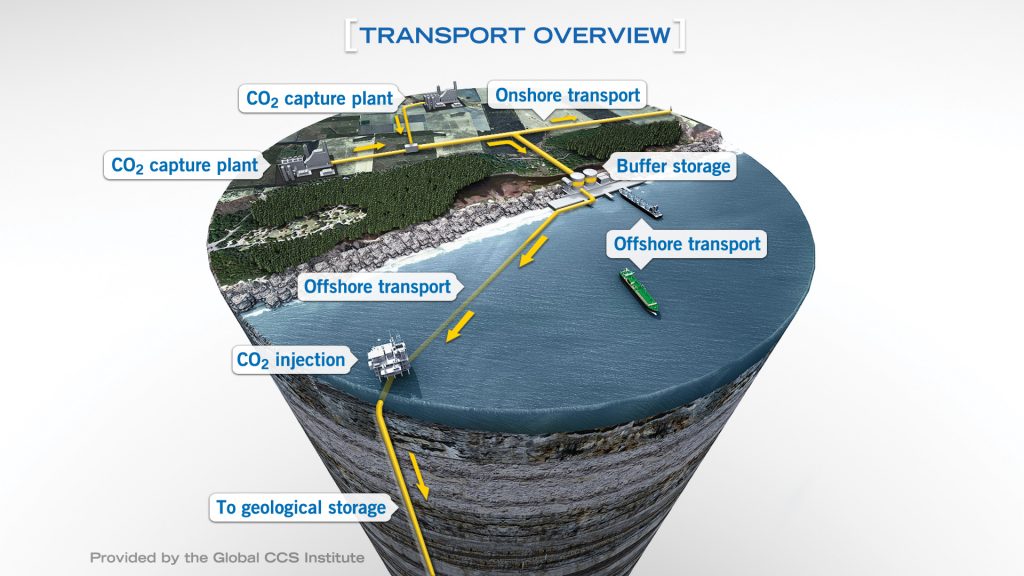

BECCS and DACCS also have to consider wider supply chains, such as carbon transport and storage infrastructure. Although this requires a high initial investment, by connecting to industrial emitters, it can enable providers to recover the costs through charges to multiple network users.

Ultimately, the key to making any GGR policies work effectively and efficiently is speed. In order to put in place accounting principles, test different methods, and begin courting investors, government needs to act now.

The Vivid Economics report “is further confirmation of the vital role that BECCS will play in reaching a net zero-carbon economy and the need to deploy the UK’s first commercial project in the 2020s,” Drax Group CEO Will Gardiner says.

“Our successful BECCS pilot is already capturing a tonne of carbon a day. With the right policies in place, Drax could become the world’s first negative emissions power station and the anchor for a zero carbon economy in the Humber region.”

It will be significantly more cost efficient to begin deploying GGR in the next decade and slowly increase it up to the level of 130 MtCO2 per year, than attempting to rapidly build infrastructure in the 2040s in a last-ditch effort to meet carbon neutrality by 2050.

Read the Vivid Economics report for BEIS, Greenhouse Gas Removal (GGR) policy options – Final Report. Our response is here. Read an overview of negative emissions techniques and technologies. Find out more about Zero Carbon Humber, the Drax, Equinor and National Grid Ventures partnership to build the world’s first zero carbon industrial cluster and decarbonise the North of England.

Learn more about carbon capture, usage and storage in our series:

Logistics (road, air and sea freight)

Logistics (road, air and sea freight) Personnel travel

Personnel travel Factories and facilities

Factories and facilities Events

Events Total F1 car emissions including all race and test mileage

Total F1 car emissions including all race and test mileage