https://electricinsights.co.uk/

https://electricinsights.co.uk/

To tackle the climate crisis, global unity and collaboration are needed. This was in part the thinking behind the Paris Agreement. It set a clear, collective target negotiated at the 2015 United Nations Climate Change Conference and signed the following year: to keep the increase in global average temperatures to well below 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels.

In November 2021, COP26 will see many of the countries who first signed the Paris Agreement come together in Glasgow for the first ‘global stocktake’ of their environmental progress since its creation.

COP26 will take place at the SEC in Glasgow

Already delayed for a year as a result of the pandemic, COVID-19 and its effects on emissions is likely to be a key talking point. So too will progress towards not just the Paris Agreement goals but those of individual countries. Known as ‘National Determined Contributions’ (NDCs), these sit under the umbrella of the Paris Agreement goals and set out individual targets for individual countries.

With many countries still reeling from the effects of COVID-19, the question is: which countries are actually on track to meet them?

The NDCs of each country represent its efforts and goals to reduce national emissions and adapt to the impacts of climate change. These incorporate various targets, from decarbonisation and forestry to coastal preservation and financial aims.

While all countries need to reduce emissions to meet the Paris Agreement targets, not all have an equally sized task. The principle of differentiated responsibility acknowledges that countries have varying levels of emissions, capabilities and economic conditions.

The Universal Ecological Fund outlined the emissions breakdown of the top four emitters, showing that combined, they account for 56% of global greenhouse gas emissions. China is the largest emitter, responsible for 26.8%, followed by the US which contributes 13.1%. The European Union and its 28 member states account for nine per cent, while India is responsible for seven per cent of all emissions.

These nations have ambitious emissions goals, but are they on track to meet them?

Traffic jams in the rush hour in Shanghai Downtown, contribute to high emissions in China.

By 2030, China pledged to reach peak carbon dioxide (CO2), increase its non-fossil fuel share of energy supply to 20% and reduce the carbon intensity – the ratio between emissions of CO2 to the output of the economy – by 60% to 65% below 2005 levels.

COVID-19 has increased the uncertainty of the course of China’s emissions. Some projections show that emissions are likely to grow in the short term, before peaking and levelling out sometime between 2021 and 2025. However, according to the Climate Action Tracker it is also possible that China’s emissions have already peaked – specifically in 2019. China is expected to meet its non-fossil energy supply and carbon intensity pledges.

The forecast for the second largest emitter, the US, has also been affected by the pandemic. Economic firm Rhodium Group has predicted that the US could see its emissions drop between 20% and 27% by 2025, meeting its target of reducing emissions by 26% to 28% below 2005 levels.

However, President Trump’s rolling back of Obama-era climate policies and regulations, his support of fossil fuels and withdrawal from the Paris Agreement (effective from as early as 4 November 2020), suggest any achievement may not be long-lasting.

The United States’ Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act, known as the CARES Act, does not include any direct support to clean energy development – something that could also change in 2021.

Carl Clayton, Head of BECCS at Drax, inspects pipework in the CCUS area of Drax Power Station

The European Union and its member states, then including the UK, pledged to reduce emissions by at least 40% below 1990 levels by 2030 – a target the Climate Action Tracker estimates will be achieved. In fact, the EU is on track to cut emissions by 58% by 2030.

This progress is in part a result of a large package of measures adopted in 2018. These accelerated the emissions reductions, including national coal phase-out plans, increasing renewable energy and energy efficiency. The package also introduced legally binding annual emission limits for each member state within which they can set individual targets to meet the common goal.

The UK has not yet released an updated, independent NDC. However, it has announced a £350 million package designed to cut emissions in heavy industry and drive economic recovery from COVID-19. This includes £139 million earmarked to scale up hydrogen production, as well as carbon capture and storage (CCS) technology, such as bioenergy with carbon capture (BECCS) – essential technologies in achieving net zero emissions by 2050 and protecting industrial regions.

India, the fourth largest global emitter, is set to meet its pledge to reduce its emissions intensity by 33% to 35% below 2005 levels and increase the non-fossil share of power generation to 40% by 2030. What’s more, the Central Electricity Agency has reported that 64% of India’s power could come from non-fossil fuel sources by 2030.

Wind turbines in Jaisalmer, Rajasthan, India

Along with increasingly renewable generation, the implementation of India’s National Smart Grid Mission aims to modernise and improve the efficiency of the country’s energy system.

It is promising that the world’s four largest emitters have plans in place and are making progress towards their decarbonisation goals. However, tackling climate change requires action from around the entire globe. In addition to NDCs, many countries have committed to, or have submitted statements of intent, to achieve net zero carbon emissions in the coming years.

| Country | Target Date | Status |

|---|---|---|

Bhutan  | Currently carbon negative (and aiming for carbon neutrality as it develops; pledged towards the Paris Agreement) | |

Suriname  | Currently carbon negative | |

Denmark  | 2050 | In law |

France  | 2050 | In law |

Germany  | 2050 | In law |

Hungary  | 2050 | In law |

New Zealand  | 2050 | In law |

Scotland  | 2045 | In law |

Sweden  | 2045 | In law |

United Kingdom  | 2050 | In law |

Bulgaria  | 2050 | Policy Position |

Canada  | 2050 | Policy Position |

Chile  | 2050 | In policy |

China  | 2060 | Statement of intent |

Costa Rica  | 2050 | Submitted to the UN |

EU  | 2050 | Submitted to the UN |

Fiji  | 2050 | Submitted to the UN |

Finland  | 2035 | Coalition agreement |

Iceland  | 2040 | Policy Position |

Ireland  | 2050 | Coalition Agreement |

Japan  | 2050 | Policy Position |

Marshall Islands  | 2050 | Pledged towards the Paris Agreement |

Netherlands  | 2050 | Policy Position |

Norway  | 2050 in law, 2030 signal of intent | |

Portugal  | 2050 | Policy Position |

Singapore  | As soon as viable in the second half of the century | Submitted to the UN |

Slovakia  | 2050 | Policy Position |

South Africa  | 2050 | Policy Position |

South Korea  | 2050 | Policy Position |

Spain  | 2050 | Draft Law |

Switzerland  | 2050 | Policy Position |

Uruguay  | 2030 | Contribution to the Paris Agreement |

While the COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted short-term plans, many see it as an opportunity to rejuvenate economies with sustainability in mind. COP26, as well as the global climate summit planned for December of this year, will likely see many countries lay out decarbonisation goals that benefit both people’s lives and the planet.

#COP26, as well as the UK/UN climate meeting planned for this December, will likely see many countries lay out decarbonisation goals that benefit both people’s lives and the planet. #COP26countdown

#COP26Ambition

— Drax (@DraxGroup) October 30, 2020

Today our organisations have launched a new coalition with a shared vision: to build back better as part of a sustainable and resilient recovery from Covid-19, by developing pioneering projects that can remove carbon dioxide (CO2) and other pollutants from the atmosphere. Together, we represent hundreds of thousands of workers across some of the UK’s most critical industries, including aviation, energy and farming, each of which contribute billions of pounds each year to the economy.

A growing number of independent experts, including the Committee on Climate Change, Royal Society and Royal Academy of Engineering and the Electricity System Operator, have recognised the crucial role of ‘negative emissions’ or ‘greenhouse gas removal’ technologies in fighting the climate crisis. Whilst we should seek to decarbonise sectors such as aviation, heavy industry and agriculture as far as practically possible, due to technical or commercial barriers it is unlikely we will eliminate their greenhouse gas emissions completely. Negative emissions technologies are critical therefore to balancing out these residual emissions and ensuring we achieve Net Zero in a credible, cost effective and sustainable way.

As well as benefiting the environment, negative emissions technologies and projects can build back a cleaner, greener economy in the wake of Covid-19. The foundations for this are already being laid by our coalition’s members today.

For example:

With COP26 fast approaching, there is a real and compelling opportunity for the UK Government to demonstrate to the world it is taking a leadership position on negative emissions. Conversely if the UK does not act quickly, it could jeopardise the delivery of projects in the 2020s that can support innovation, learning by doing and the scale-up of negative emissions in the 2030s. It also risks Britain falling behind in the race to scale and commercialise these technologies, with a view to exporting them to other countries around the world to support their own decarbonisation efforts.

We would welcome the opportunity to meet with each of you to discuss these points in further detail.

Yours,

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

Emissions are at their lowest in modern times, having fallen by three-quarters compared to the same period ten years ago. The average carbon emissions fell to a new low of 153 grams per kWh of electricity consumed over the quarter.

The carbon intensity also plummeted to a new low of just 18 g/kWh in the middle of the Spring Bank Holiday. Clear skies with a strong breeze meant wind and solar power dominated the generation mix.

Together, nuclear and renewables produced 90% of Britain’s electricity, leaving just 2.8 GW to come from fossil fuels.

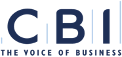

The generation mix over the Spring Bank Holiday weekend, highlighting the mix on the Sunday afternoon with the lowest carbon intensity on record

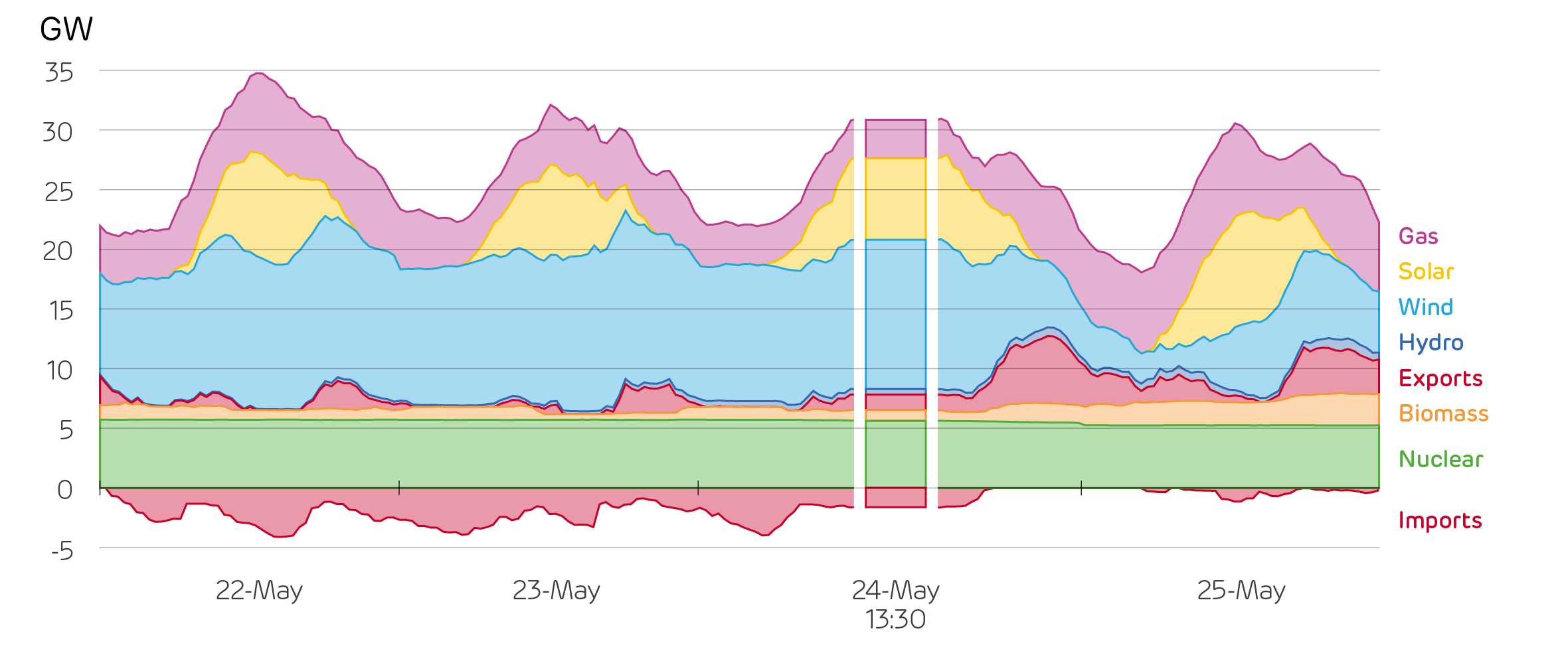

National Grid and other grid-monitoring websites reported the carbon intensity as being 46 g/kWh at that time. That was still a record low, but very different from the Electric Insights numbers. So why the discrepancy?

These sites report the carbon intensity of electricity generation, as opposed to consumption. Not all the electricity we consume is generated in Britain, and not all the electricity generated in Britain is consumed here.

Should the emissions from power stations in the Netherlands ‘count’ towards our carbon footprint, if they are generating power consumed in our homes? Earth’s atmosphere would say yes, as unlike air pollutants which affect our cities, CO2 has the same effect on global warming regardless of where it is produced.

On that Bank Holiday afternoon, Britain was importing 2 GW of electricity from France and Belgium, which are mostly powered by low-carbon nuclear. We were exporting three-quarters of this (1.5 GW) to the Netherlands and Ireland. While they do have sizeable shares of renewables, they also rely on coal power.

Britain’s exports prevented more fossil fuels from being burnt, whereas the imports did not as they came predominantly from clean sources. So, the average unit of electricity we were consuming at that point in time was cleaner than the proportion of it that was generated within our borders. We estimate that 1190 tonnes of CO2 were produced here, 165 were emitted in producing our imports, and 730 avoided through our exports.

In the long-term it does not particularly matter which of these measures gets used, as the mix of imports and exports gets averaged out. Over the whole quarter, carbon emissions would be 153g/kWh with our measure, or 151 g/kWh with production-based accounting. But, it does matter on the hourly timescale, consumption based accounting swings more widely.

Imports and exports helped make the electricity we consume lower carbon on the 24th, but the very next day they increased our carbon intensity from 176 to 196 g/kWh.

When renewable output is high in Britain we typically export the excess to our neighbours as they are willing to pay more for it, and this helps to clean their power systems. When renewables are low, Britain will import if power from Ireland and the continent is lower cost, but it may well be higher carbon.

Two measures for the carbon intensity of British electricity over the Bank Holiday weekend and surrounding days

This speaks to the wider question of decarbonising the whole economy.

Should we use production or consumption based accounting? With production (by far the most common measure), the UK is doing very well, and overall emissions are down 32% so far this century. With consumption-based accounting it’s a very different story, and they’re only down 13%*.

This is because we import more from abroad, everything from manufactured goods to food, to data when streaming music and films online.

Either option would allow us to claim we are zero carbon through accounting conventions. On the one hand (production-based accounting), Britain could be producing 100% clean power, but relying on dirty imports to meet its entire demand – that should not be classed as zero carbon as it’s pushing the problem elsewhere. On the other hand (consumption-based accounting), it would be possible to get to zero carbon emissions from electricity consumed even with unabated gas power stations running. If we got to 96% low carbon (1300 MW of gas running), we would be down at 25 g/kWh. Then if we imported fully from France and sent it to the Netherlands and Ireland, we’d get down to 0 g/kWh.

Regardless of how you measure carbon intensity, it is important to recognise that Britain’s electricity is cleaner than ever.

The hard task ahead is to make these times the norm rather than the exception, by continuing to expand renewable generation, preparing the grid for their integration, and introducing negative emissions technologies such as BECCS (bioenergy with carbon capture and storage).

Read full Report (PDF) | Read full Report | Read press release

Reaching the UK’s target of net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050 means every aspect of the economy, from shops to super computers, must reduce its carbon footprint – all the way down their supply chains – as close to zero as possible.

But as the country transforms, one thing is certain: demand for electricity will remain. In fact, with increased electrification of heating and transport, there will be a greater demand for power from renewable, carbon dioxide (CO2)-free sources. Bioenergy is one way of providing this power without reliance on the weather and can offer essential grid-stability services, as provided by Drax Power Station in North Yorkshire.

Close up of electricity pylon tower

Beyond just power generation, more and more reports highlight the important role the next evolution of bioenergy has to play in a net zero UK. And that is bioenergy with carbon capture and storage or BECCS.

The Committee on Climate Change (CCC) says negative emissions are essential for the UK to offset difficult-to-decarbonise sectors of the economy and meet its net zero target. This may include direct air capture (DAC) and other negative emissions technologies, as well as BECCS.

BECCS power generation uses biomass grown in sustainably managed forests as fuel to generate electricity. As these forests absorb CO2 from the atmosphere while growing, they offset the amount of CO2 released by the fuel when used, making the whole power production process carbon neutral. Adding carbon capture and storage to this process results in removing more CO2 from the atmosphere than is emitted, making it carbon negative.

Pine trees grown for planting in the forests of the US South where more carbon is stored and more wood inventory is grown each year than fibre is extracted for wood products such as biomass pellets

This means BECCS can be used to abate, or offset, emissions from other parts of the economy that might remain even as it decarbonises. A report by The Energy Systems Catapult, modelling different approaches for the UK to reach net zero by or before 2050, suggests carbon-intensive industries such as aviation and agriculture will always produce residual emissions.

The need to counteract the remaining emissions of industries such as these make negative emissions an essential part of reaching net zero. While the report suggests that direct air carbon capture and storage (DACCS) will also play an important role in bringing CO2 levels down, it will take time for the technology to be developed and deployed at the scale needed.

Meanwhile, carbon capture use and storage (CCUS) technology is already deployed at scale in Norway, the US, Australia and Canada. These processes for capturing and storing carbon are applicable to biomass power generation, such as at Drax Power Station, which means BECCS is ready to deploy at scale from a technology perspective today.

As well as counteracting remaining emissions, however, BECCS can also help to decarbonise other industries by enabling the growth of a different low carbon fuel: hydrogen.

The CCC’s ‘Hydrogen in a low-carbon economy report’ highlights the needs for carbon zero alternatives to fossil fuels – in particular, hydrogen or H2.

Hydrogen produced in a test tube

When combusted, hydrogen only produces heat and water vapour, while the ability to store it for long periods makes it a cleaner replacement to the natural gas used in heating today. Hydrogen can also be stored as a liquid, which, coupled with its high energy density makes it a carbon zero alternative to petrol and diesel in heavy transport.

There are various ways BECCS can assist the creation of a hydrogen economy. Most promising is the use of biomass to produce hydrogen through a method known as gasification. In this process solid organic material is heated to more than 700°C but prevented from combusting. This causes the material to break down into gases: hydrogen and carbon monoxide (CO). The CO then reacts with water to form CO2 and more H2.

While CO2 is also produced as part of the process, biomass material absorbs CO2 while it grows, making the overall process carbon neutral. However, by deploying carbon capture here, the hydrogen production can also be made carbon negative.

BECCS can more indirectly become an enabler of hydrogen production. The Zero Carbon Humber partnership envisages Drax Power Station as the anchor project for CCUS infrastructure in the region, allowing for the production of ‘blue’ hydrogen. Blue hydrogen is produced using natural gas, a fossil fuel. However, the resulting carbon emissions could be captured. The CO2 would then be transported and stored using the same system of pipelines and a natural aquifer under the North Sea as used by BECCS facilities at Drax.

This way of clustering BECCS power and hydrogen production would also allow other industries such as manufactures, steel mills and refineries, to decarbonise.

One of the challenges in transforming the energy system and wider economy to net zero is accounting for the cost of the transition.

The Energy Systems Catapult’s analysis found that it could be kept as low as 1-2% of GDP, while a report by the National Infrastructure Commission (NIC) projects that deploying BECCS would have little impact on the total cost of the power system if deployed for its negative emissions potential.

The NIC’s modelling found, when taking into consideration the costs and generation capacity of different sources, BECCS would likely be run as a baseload source of power in a net zero future. This would maximise its negative emissions potential.

This means BECCS units would run frequently and for long periods, uninterrupted by changes in the weather, rather than jumping into action to account for peaks in demand. This, coupled with its ability to abate emissions, means BECCS – alongside intermittent renewables such as wind and solar – could provide the UK with zero carbon electricity at a significantly lower cost than that of constructing a new fleet of nuclear power stations.

The report also goes on to say that a fleet of hydrogen-fuelled power stations could also be used to generate flexible back-up electricity, which therefore could be substantially cheaper than relying on a fleet of new baseload nuclear plants.

However, for this to work effectively, decisions need to be made sooner rather than later as to what approach the UK takes to shape the energy system before 2050.

What is consistent across many different reports is that BECCS will be essential for any version of the future where the UK reaches net zero by 2050. But, it will not happen organically.

Sunset and evening clouds over the River Humber near Sunk Island, East Riding of Yorkshire

A joint Royal Society and Royal Academy of Engineering Greenhouse Gas Removal report, includes research into BECCS, DACCS and other forms of negative emissions in its list of key actions for the UK to reach net zero. It also calls for the UK to capitalise on its access to natural aquifers and former oil and gas wells for CO2 storage in locations such as the North Sea, as well as its engineering expertise, to establish the infrastructure needed for CO2 transport and storage.

However, this will require policies and funding structures that make it economical. A report by Vivid Economics for the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) highlights that – just as incentives have made wind and solar viable and integral parts of the UK’s energy mix – BECCS and other technologies, need the same clear, long-term strategy to enable companies to make secure investments and innovate.

However, for policies to make the impact needed to ramp BECCS up to the levels necessary to bring the UK to net zero, action is needed now. The report outlines policies that could be implemented immediately, such as contracts for difference, or negative emissions obligations for residual emitters. For BECCS deployment to expand significantly in the 2030s, a suitable policy framework will need to be put in place in the 2020s.

Beyond just decarbonising the UK, a report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) highlights that BECCS could be of even more importance globally. Differing scales of BECCS deployment are illustrated in its scenarios where global warming is kept to within 1.5oC levels of pre-industrial levels, as per the Paris Climate agreement.

BECCS has the potential to play a vital role in power generation, creating a hydrogen economy and offsetting other emissions. As it continues to progress, it is becoming increasingly effective and cost efficient, offering a key component of a net zero UK.

How reliable is Great Britain’s electricity system? Across the country electricity is accessible and safe to use for just about everyone, every day. Wide-scale blackouts are very rare, but they do happen.

On 9 August 2019 a power cut saw more than 1 million people and services lose power for just under an hour. It was the first large-scale blackout since 2013. Although this proves the network is not infallible, the fact it was such an outlier in the normal performance of the grid highlights its otherwise exemplary stability and reliability.

But what is it exactly that makes an electricity system stable and reliable?

At its core, system stability comes down to two key factors: a country or region’s ability to generate enough electricity, and its ability to then transport it through a transmission system to where it’s needed.

When everything is running smoothly an electricity system is described as being ‘balanced’. In this state supply meets demand exactly and all necessary conditions – such as voltage and frequency – are right for the safe and efficient transport of electricity. Any slight deviation or mismatch across any of these factors can cause power stations or infrastructure to trip and cut off power.

A recent report by Electric Insights identified the countries around the world with most reliable power systems, in which the UK was fourth. It offers an insight into what factors contribute to building a stable system, as well as those that hold some countries back.

According to the report, France has the most reliable electricity system of any country with a population of more than five million people, having gone a decade without a power outage. One reason for this is the country’s fleet of 58 state-controlled nuclear power stations which generate huge amounts of consistent baseload power.

In 2017 nuclear power made up more than 70% of France’s electricity generation while hydropower accounted for another 10% of the 475 Terawatt hours (TWh) consumed across the county that year.

Penly Nuclear Power Station near Dieppe, France.

Now, as its nuclear stations age, France is increasing its renewable power generation. As these sources are often weather dependent, imports from and exports to its neighbours are expected to become a more important part of keeping the French network stable at times when there is little sunlight or wind – or too much.

Importing and exporting electricity is also key to Switzerland’s power system (third most reliable network on the list), with 41 border-crossing power lines allowing the country to serve as a crossroads for power flowing between Italy and Germany. It means its total imports and exports can often exceed electricity production within the country.

Electricity pylons in Switzerland.

Switzerland’s mountainous landscape also means ensuring a reliable electricity system requires a carefully maintained transmissions system. The Swiss grid is 6,700 kilometres long and uses 40,000 hi-tech metering points along it to record and process around 10,000 data points in seconds.

The key to the stability of South Korea – the second most stable network on the list – is also its imports, but rather than actual megawatts it comes in the form of oil, gas and coal. The country is the world’s fourth biggest coal importer and its coal power stations account for 42% of its total generation.

Seoul, South Korea.

However, in the face of urban smog issues and global decarbonisation goals it is pursuing a switch to renewables. This can come with repercussions to stability, so South Korea is also investing in transmission infrastructure, including a new interconnector from the east of the country to Seoul, its main source of electricity consumption.

It highlights that if decarbonisation is going to accelerate at the pace needed to meet Paris Agreement targets, then many of the world’s most stable and reliable electricity systems need to go through significant change. Balance will be needed between meeting decarbonisation targets with overall system stability.

However, there are many countries around the world that focus less on ensuring consistent stability through decarbonisation and are instead more focused on how to achieve stability in the first place.

The Democratic Republic of Congo is the eleventh-largest country on earth. It is rich with minerals and resources, yet it is the least electrified nation. Just 9% of people have access to power (in rural areas that number drops to just 1%) and the country suffers blackouts more than once a month as a result of ‘load shedding’, when there isn’t enough power to meet demand so parts of the grid are deliberately shut down to prevent the entire system failing.

Currently, the country has just 2.7 GW of installed electricity capacity, 2.5 GW of which comes from hydropower. The country’s Inga dam facility on the Congo river has the potential to generate more electricity than any other single source of power on the planet (it’s thought the proposed Grand Inga site could produce as much as 40 GW, twice that of China’s Three Gorges Dam) and provide electricity to a massive part of southern Africa. A legacy of political instability in the country, however, has so far made securing financing difficult.

Congo River, Democratic Republic of Congo.

Nigeria is one of the world’s fastest growing economies, and with that comes rapidly rising demand for electricity. However, just 45% of the country is currently electrified, and of these areas, many still suffer outages at least once a month. The country has 12.5 GW of installed capacity, most of which comes from thermal gas stations, but technical problems in power stations and infrastructure, mean it is often only capable of generating as much as 5 GW to transmit on to end consumers.

This limited production capability means it often fails to meet demand, resulting in outages. The problem has been prolonged by struggling utility companies that are unable to make the investments needed to stabilise electricity supply.

Keen to resolve what it has referenced as an ‘energy supply crisis’, the Nigerian government recently secured a $1 billion credit line from the World Bank to improve access to electricity across the country.

The investment will focus in part on securing the transmission system from theft, thus allowing the private utility companies to generate the revenue needed to improve generation.

Balancing transmissions systems is a crucial part of stable electricity networks. Maintaining a steady frequency that delivers safe, usable electricity into homes and businesses is at the crux of reliability. Even countries that can generate enough electricity are held back if they can’t efficiently get the electricity to where it is needed.

Brazil has an abundance of hydropower installed. Its 97 GW of hydro accounts for more than 70% of the country’s electricity mix. However, the country’s dams are largely concentrated around the Amazon basin in the North West, whereas demand comes from cities in the south and eastern coastline. Transporting electricity across long distances between generator and consumer makes it difficult to maintain the correct voltage and frequency needed to keep a stable and reliable flow of electricity. As a result, Brazil suffers a blackout every one-to-three months.

Hydropower plant Henry Borden in the Serra do Mar, Brazil.

The country is tackling its transmissions problems by diversifying its electricity mix to include greater levels of solar and wind off its east coast – closer to many of its major cities. The country has also looked to new technology for solutions.

At the start of the decade as much as 8% of all electricity being generated in Brazil was being stolen, reaching as high as 40% in some areas. These illegal hookups both damage infrastructure, making it less reliable, as well as blur the true demand, making grid management challenging.

Brazil has since deployed smart meters to measure electricity’s journey from power stations to end users more accurately, allowing operators to spot anomalies sooner. Electricity theft is a major problem in many developing regions, with as much as $10 billion worth of power lost each year in India, which suffers blackouts as often as Brazil.

It highlights that even when there is generation to meet demand, maintaining stability at a large scale requires constant attention and innovation as new challenges arise.

This looks different around the world. Some countries might face challenges in shifting from stable thermal-based systems to renewables, others are attempting to build stability into newly connected networks. But no matter where in the world electricity is being used, ensuring reliability is an ever-ongoing task.

Electric Insights is commissioned by Drax and delivered by a team of independent academics from Imperial College London, facilitated by the college’s consultancy company – Imperial Consultants. The quarterly report analyses raw data made publicly available by National Grid and Elexon, which run the electricity and balancing market respectively, and Sheffield Solar. Read the full Q3 2019 Electric Insights report or download the PDF version.

Over the past decade the United Kingdom has decarbonised significantly as coal power has been replaced by sources like biomass, wind and solar. Every year power generation emits fewer and fewer tonnes of carbon thanks to renewables and with the ban on the sale of new diesel and petrol cars coming in no later than 2040, roads and urban areas are about to get cleaner too.

However, there are still tough challenges ahead if the UK is to meet its target of carbon neutrality by 2050. Aviation, heavy industry, agriculture, shipping, power generation – some of the key activities of daily economic life – all remain reliant on fuels that emit carbon.

This is where Greenhouse Gas Removal (GGR) technologies have a big role to play. These can capture carbon dioxide (CO2) and other greenhouse gases from the atmosphere, and either store them or use them, helping the drive towards carbon neutrality.

While the idea of being able to capture carbon has been around for some time, the technology is fast catching up with the ambition. There now exist a number of credible solutions that allow for capturing emissions. The challenge, however, is putting in place the framework and policies needed to enable technologies to be implemented at scale.

Time is short. A recent report by Vivid Economics for the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) emphasised the need for government action now if we are to achieve the volume of carbon removal needed to achieve net zero emissions by 2050.

The planet naturally absorbs CO2, forests absorb it as they grow, mangroves trap it in flooded soils, and oceans absorb it from the air. So, harnessing this power through planting, growing and actively managing forests is one natural method of GGR that can be easily implemented by policy.

Aerial view of mangrove forest and river on the Siargao island. Philippines.

The idea of using technology to capture CO2 and prevent its release into the atmosphere has been around since the 1970s. It was first deployed successfully in enhanced oil recovery, when captured emissions are injected into underground oil reserves to help remove the oil from the ground.

Over time it’s been developed and is now in place in a number of fossil fuel power stations around the world, allowing them to cut emissions. However, by combining the same technology with renewable fuels like compressed biomass wood pellets, we can generate electricity that is carbon negative.

Each of these solutions operate in different ways, but all are important. Vivid Economics’ report emphasises that a range of different solutions will be required to reach a point where 130 million tonnes of CO2 (MtCO2) are being removed from the atmosphere in the UK annually by 2050.

However, investment and clear government planning and guidance will be crucial in enabling the growth of GRR. The report estimates large-scale GGR could cost around £13 billion per year by 2050 in the UK alone, a figure similar in size to current government support for renewables.

“If you went back 20-odd years, people were sceptical of the role of wind, solar and biomass and whether the technologies would ever get to a cost point where they could be viably deployed at scale,” explains Drax Policy Analyst Richard Gow.

“In the last few years we’ve seen enormous cost reductions in renewables and people are far more confident in investing in them – that has been driven by very good government policy.”

GGR needs the same clear long-term strategy to enable companies to make secure investments and innovate. But what shape should those policies take for them to be effective?

Perhaps the most straightforward route to enabling GGR is to build on existing policies. For example, there are existing tree planting schemes such as the Woodland Carbon Fund, Woodland Carbon Code and the Country Stewardship Scheme, all of which could receive greater regulatory support, or additional rules obliging emitters to invest in actively managed forests.

More technically complex solutions, like bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS) and direct air carbon capture and storage (DACCS), could be incentivised by alternative mechanisms in order to provide clarity on, and to stabilise, revenue streams. These are already used to support companies building low-carbon power generation such as through the Contracts for Difference scheme and have been effective in encouraging investment in projects with high upfront costs and long-payback periods.

Alternative options to support the roll-out of negative emissions technologies should also be considered. For example, the government could make it obligatory for companies that contribute to emissions, to pay for GGR to avoid increased burden on electricity consumers.

In such a scenario, fossil fuel suppliers would be required to offset the emissions of their products by buying negative emissions certificates from GGR providers. As a result, the price of fossil fuels for users would likely rise to cover this expense and the costs would then be shared across the supply chain rather than just a single party.

Another approach that passes the costs of GGR deployment on to emitters is using emissions taxes to fund tax credits for GGR providers.

Making these tax credits tradable would also mean any large tax-paying company, such as a supermarket or bank, could buy tax credits from GGR providers. This approach would come at no cost to government as sales of the tax credits would be funded by an emissions tax and would offer revenue to GGR providers.

The challenge with tax credits, however, is they are vulnerable to changes in government. An alternative is to offer direct grants and long-term contracts with GGR providers which would ensure funding for projects that transcends changes in Parliament. They could, however, prove costly for government.

Whatever policy pathway the government may choose to follow, there are underlying foundations needed to support effective GGR deployment.

There are still many unknown factors in GGR deployment, such as the precise volume that will be needed to counter hard-to-abate emissions. This means all policy must be flexible to allow for future changes, and the individual requirements of different regions (forest-based solutions might suit some regions, DACCS might be better in others).

Underlying the strength of any of these policies, is the need for accurate carbon accounting. Understanding how much emissions are removed from the atmosphere by each technology will be key to reaching a true net zero status and giving credibility to certificates and tax credits.

Pearl River Nursery, Mississippi

Proper accounting of different technologies’ impact will also be crucial in delivering innovation grants. These can come through the UK’s existing innovation structure and will be fundamental to jumpstarting the pilot programmes needed to test the viability of GGR approaches before commercialisation.

Different approaches to GGR have different levels of effectiveness as well as different costs. BECCS, for example, serves two purposes in both generating low-carbon power and capturing emissions – resulting in overall negative emissions across the supply chain.

“It’s important to account for the full value chain of BECCS,” explains Gow. “Therefore, it should be rewarded through two mechanisms: a CfD for the clean electricity produced and an incentive for the negative emissions. A double policy here is important because you are providing two products which benefit different sectors of the economy, one benefits power consumers and the other provides a service to society and the environment as a whole, and cost should be apportioned as such.

BECCS and DACCS also have to consider wider supply chains, such as carbon transport and storage infrastructure. Although this requires a high initial investment, by connecting to industrial emitters, it can enable providers to recover the costs through charges to multiple network users.

Ultimately, the key to making any GGR policies work effectively and efficiently is speed. In order to put in place accounting principles, test different methods, and begin courting investors, government needs to act now.

The Vivid Economics report “is further confirmation of the vital role that BECCS will play in reaching a net zero-carbon economy and the need to deploy the UK’s first commercial project in the 2020s,” Drax Group CEO Will Gardiner says.

“Our successful BECCS pilot is already capturing a tonne of carbon a day. With the right policies in place, Drax could become the world’s first negative emissions power station and the anchor for a zero carbon economy in the Humber region.”

It will be significantly more cost efficient to begin deploying GGR in the next decade and slowly increase it up to the level of 130 MtCO2 per year, than attempting to rapidly build infrastructure in the 2040s in a last-ditch effort to meet carbon neutrality by 2050.

Read the Vivid Economics report for BEIS, Greenhouse Gas Removal (GGR) policy options – Final Report. Our response is here. Read an overview of negative emissions techniques and technologies. Find out more about Zero Carbon Humber, the Drax, Equinor and National Grid Ventures partnership to build the world’s first zero carbon industrial cluster and decarbonise the North of England.

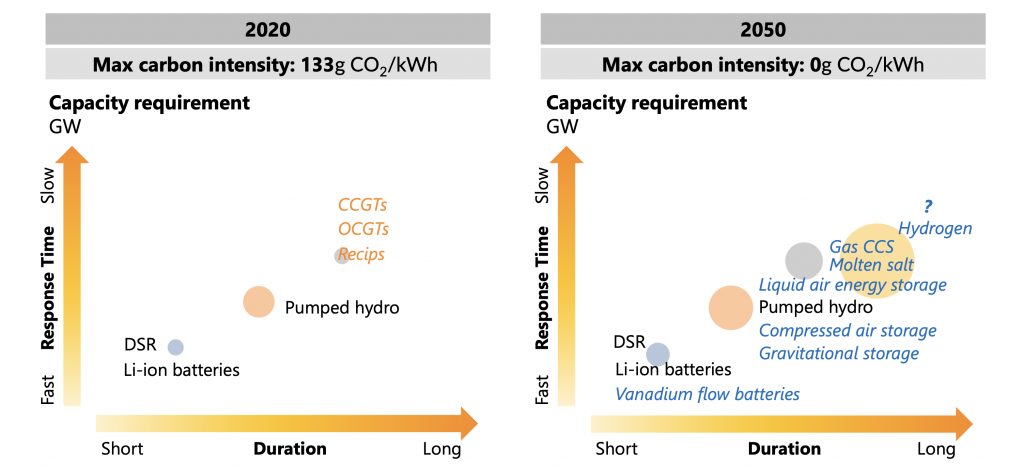

Great Britain’s electricity system is in the middle of a revolution. Where power supply was once dominated by some big thermal coal, gas and nuclear power stations, it now comes from an array of sources. Thousands of new individual points have been added to the mix, ranging from large interconnectors, that bring in power from neighbouring countries, through to wind farms, solar panels, small gas and diesel engines.

The energy mix has been changing radically, with low carbon sources expected to provide 58% of Great Britain’s power by 2020, up from 22% in 2010 and 53% in 2018. However, the security standards at which the electricity grid needs to be operated remain the same; these are predominantly voltage and frequency, and nominally 230 V and 50Hz for a domestic consumer.

The operation of the Transmission system, including maintaining these standards is overseen by the National Grid Electricity System Operator (ESO), using a set of vital tools it needs to have available, known as ancillary services. Some of this capability was inherent in large generators, which could provide the ancillary services required to keep a stable transmission system. Maintaining system stability, with thousands of generation points — a large part of which are not directly controllable — is increasingly challenging.

Ancillary services enable electricity to reach the end customer when and where it is required, in a safe manner, within acceptable quality standards. In addition to managing voltage and frequency levels, these standards also include maintaining adequate reserves to accommodate demand forecast uncertainties, generator breakdown and system faults. 1.

As the electricity mix changes, so must the process by which these services are secured. A diverse set of existing and genuinely new solutions will be needed to keep the lights on in the net zero carbon future.

In order for companies to help the ESO, be they generators or other service providers, it must be open and transparent about what’s needed to maintain grid stability and build resilience for the future.

“The ESO is the only buyer in the ancillary services market and is well-positioned to understand how the system is evolving. It should be proactively flagging how its needs may evolve in the future, so that the market can develop solutions to meet them”, says Marcelo Torres, Drax’s Regulation Manager – Markets.

Certain ancillary services still don’t have their own competitive markets and are provided as a “by-product” of the generation of electricity. An example is reactive power, for which there are no developed functioning regional markets yet. Generally, all power stations connected to the transmission network with a generation capacity of over 50MW are required to have the capability to provide this service, at a default price that may not reflect its real value to the system.

Another example is inertia, provided today largely through the heavy spinning turbines of thermal and pumped-storage hydro stations, which serve as stored energy that can slow down or smooth out sudden changes in network frequency.

If ancillary services were valued explicitly, market participants would have an insight into how much they are actually worth to the ESO and the grid’s stability, which would in turn incentivise new, competitive products to reach the market.

Torres points to technologies such as synchronous compensators, which are machines capable of providing ancillary services, including inertia and reactive power, without generating potentially unneeded electricity.

“These solutions will enable more renewables to connect safely to the network at a lower cost to consumers. For these solutions to come forward, ascribing the right value to ancillary services will be key. Without clear price signals, there is a risk of underinvestment in those technologies that provide the services needed, potentially resulting in price shocks for consumers”.

“The ESO is moving in the right direction with its recent Network Development Pathfinder projects. It has accelerated this work, launching its first ever tender for inertia and should roll out similar initiatives GB-wide. Such procurements should align with existing investment signals such as those provided by the Capacity Market. This should allow for the right type of capacity to be built where it is most needed, delivering a secure and resilient grid”.

“Constructing the machinery and infrastructure that will enable the ESO to operate a carbon-free system will require major financial investment, as well as years to plan and build,” says Torres.

“This can only be achieved if Ofgem designs the ESO’s incentives in a way that rewards it for taking bold, strategic initiatives that have the potential to deliver good value for money to consumers in the long-term.”

Evidence of this working is shown in the success of offshore wind, which now provide around a sixth of Great Britain’s electricity, at record low prices. This is partly due to the government providing offshore wind developers with revenue stabilisation mechanisms, known as ‘Contracts for Difference’ (CfDs).

This is not a new concept for government and regulators around the world looking to enable investment in energy infrastructure. Financing renewables to achieve decarbonisation is enabled through CfDs or market-led hedging tools, like Power Purchase Agreements. Investment to ensure there is sufficient capacity to meet peak demand is secured through long-term contracts, competitively awarded through the Capacity Market. Similarly, investment in interconnection is supported through Ofgem’s ‘Cap & Floor’ regime.

“Subsidy isn’t required for investment in ancillary services. What’s needed,” says Torres, “is a clear and stable market framework designed around the system’s needs, which provides a mix of short and long-term signals. More certainty over the market landscape and the expected returns will lower the risk of these investments and get the solutions needed at a lower overall cost to consumers.”

“Long-term procurement is not the right answer everywhere. Where there is already a mature and liquid market, such as the case for frequency response, buying services closer to real time makes sense for two reasons. First, it allows prices to reflect more accurately the market conditions and therefore the real value of a service at the time when it is needed. Second, it allows a wider range of resources to participate in the market, increasing competition. Striking the right balance between short and long-term procurement is key to create a sustainable ancillary services market.”

Currently, the ESO requests that electricity-generation firms commit to supplying a certain amount of power for the purpose of frequency response, a month ahead of time. For resources such as wind farms or solar, which are dependent on the weather, this makes it extremely difficult for them to enter this market. Even for conventional large thermal generators it can be a problem, as many of them do not know how or if they will be running beyond a few days.

“The ESO is currently conducting some trials procuring frequency response one week in advance. While this is an improvement, it is still too long a lead time for intermittent sources or demand-side response, which ideally need day-ahead or almost real time auctions to unlock their full potential,” says Torres.

“The ancillary services market has been through a prolonged period of change since the ESO published its System Needs and Product Strategy in 2017. Without knowing how the market landscape will look like by the end of these reforms, it’s difficult for providers to develop the right solutions.”

A shift in thinking, which considers what the electricity network might require in the future, and how to provide the market with financial incentives to make it a reality, is needed. A resilient, stable future system is to the advantage of consumers.

There will be no silver bullet that can solve all the challenges the energy transition poses. Maintaining system reliability in a high renewables world will require large amounts of dispatchable power, with different response time and duration. From small batteries and demand-side response that will manage instantaneously frequency fluctuations, through to large pumped storage hydro plants that will provide backup power during the days when the wind won’t blow and the sun won’t shine. A framework structured around the system’s different needs should aim at harnessing flexibility across a range of technologies and sizes.

Source: The road to 2050: The need for flexibility in a high renewables world, by Ana Barillas, Aurora (2019)

Truly diversifying will also involve unlocking the flexibility potential on the distribution grid. To achieve this, the way that access to the distribution network is managed and paid for will need to evolve. Today, with big parts of the distribution network being congested, small flexible assets are asked to wait in the queue for several years or face disproportionate amount of network reinforcement costs to get connected.

Machine hall, Cruachan Power Station

The ongoing review of the network access and forward-looking charging arrangements needs to address these barriers soon, if we are serious about making use of flexibility to foster the energy transition, while keeping consumer bills as low as possible.

Since 2018, GB’s Distribution Network Operators (DNOs) have been tendering and procuring for various flexibility services to manage congestion in regional electricity grids. In 2019, they published a roadmap setting out the steps they intend to take to enable a smarter and more flexible energy system.

“As we transition from DNOs towards Distribution System Operation – a wider set of functions and services to run a smart distribution grid – the regional networks will be open to market-based flexibility solutions. DSOs will be able to compete on a level playing field, offering options for network reinforcement. As DNOs move from trials to more structured flexibility procurement, harmonisation and effective coordination with the national markets will be the key pre-requisites to reveal the true value that flexibility can bring to the energy system,” argues Torres.

“To build a modern and resilient grid we will need a wider lens on what’s possible. It’s going to be an exciting journey on the road to net zero!”