Drax has been invited to enter formal bilateral discussions with the Government immediately, to move the project forward and ensure the Government is able to fulfil its restated commitment to achieving 5Mtpa of engineered Greenhouse Gas Removals (GGRs) by 2030. Drax believes that BECCS at Drax Power Station is the only project that can enable the Government to achieve this goal(1). The Government has also committed to publish its biomass strategy by the end of June 2023 which will set out how the technology could be deployed.

During 2022 carbon removal projects, including Power BECCS, were progressed in parallel with the Track 1 process for gas, hydrogen and industrial CCS projects. While Power BECCS and other shortlisted projects are not included in the immediate Track 1 process, the Government has confirmed that in 2023 it will set out a process for the expansion of Track 1 and has today launched Track 2. BECCS is eligible for both.

Separately, the Government has stated that it will work closely with electricity generators currently using biomass to facilitate a transition to Power BECCS.

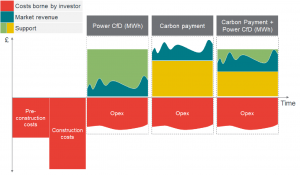

The Government has also confirmed that its response to the Power BECCS business model consultation, which took place in 2022, will be published imminently, providing further clarity on the delivery of BECCS as soon as possible.

Drax Group CEO, Will Gardiner said:

“Delivery of BECCS at Drax Power Station will help the UK achieve its net zero targets, create thousands of jobs across the north and help ensure the UK’s long-term energy security.

“We note confirmation that our project has met the Government’s deliverability criteria and Government remains committed to achieve 5Mtpa of engineered Greenhouse Gas Removals by 2030 – a goal that cannot be achieved without BECCS at Drax Power Station. We will immediately enter into formal discussions with Government to take our project forward.

“With the right engagement from Government and swift decision making, Drax stands ready to progress our £2bn investment programme and deliver this critical project for the UK by 2030.”

The Government recognises the important role which BECCS will play in delivering net zero and aims to deploy 5Mt of engineered CO2 removals per annum from BECCS and other engineered GGR technologies by 2030, rising to 23Mt in 2035 and up to 81Mt in 2050 to keep the UK on a pathway to meet its legislated climate targets, The Sixth Carbon Budget and net zero.

Drax Power Station is the UK’s largest single source of renewable electricity and BECCS is the only technology that can produce reliable renewable power, provide system support services and permanently remove CO2 at scale.

Coal closure

Drax continues to expect to close its two legacy coal units at the end of March 2023.

Notes

(1) In its Energy White Paper, Government noted that biomass is unique amongst renewable technologies in the wide array of applications in which it can be used as a substitute for fossil-fuel based products and activities, along with its ability to deliver permanent carbon removals.

Government recognises that biomass is one of the UKs most valuable tools for reaching net zero emissions while maintaining energy security.

Biomass is the only large-scale source of dispatchable, renewable electricity and Drax power station in Yorkshire is the largest provider of secure supply in the UK’s electricity system. Its renewable biomass generation provides 2.6GW of electricity, representing 4% of the UK’s dispatchable capacity and supplies millions of homes and businesses with dispatchable, reliable power.

The project at Drax Power Station is expected to be the world’s biggest engineered carbon removal project, permanently removing 8Mt of CO2 from the atmosphere every year by 2030.

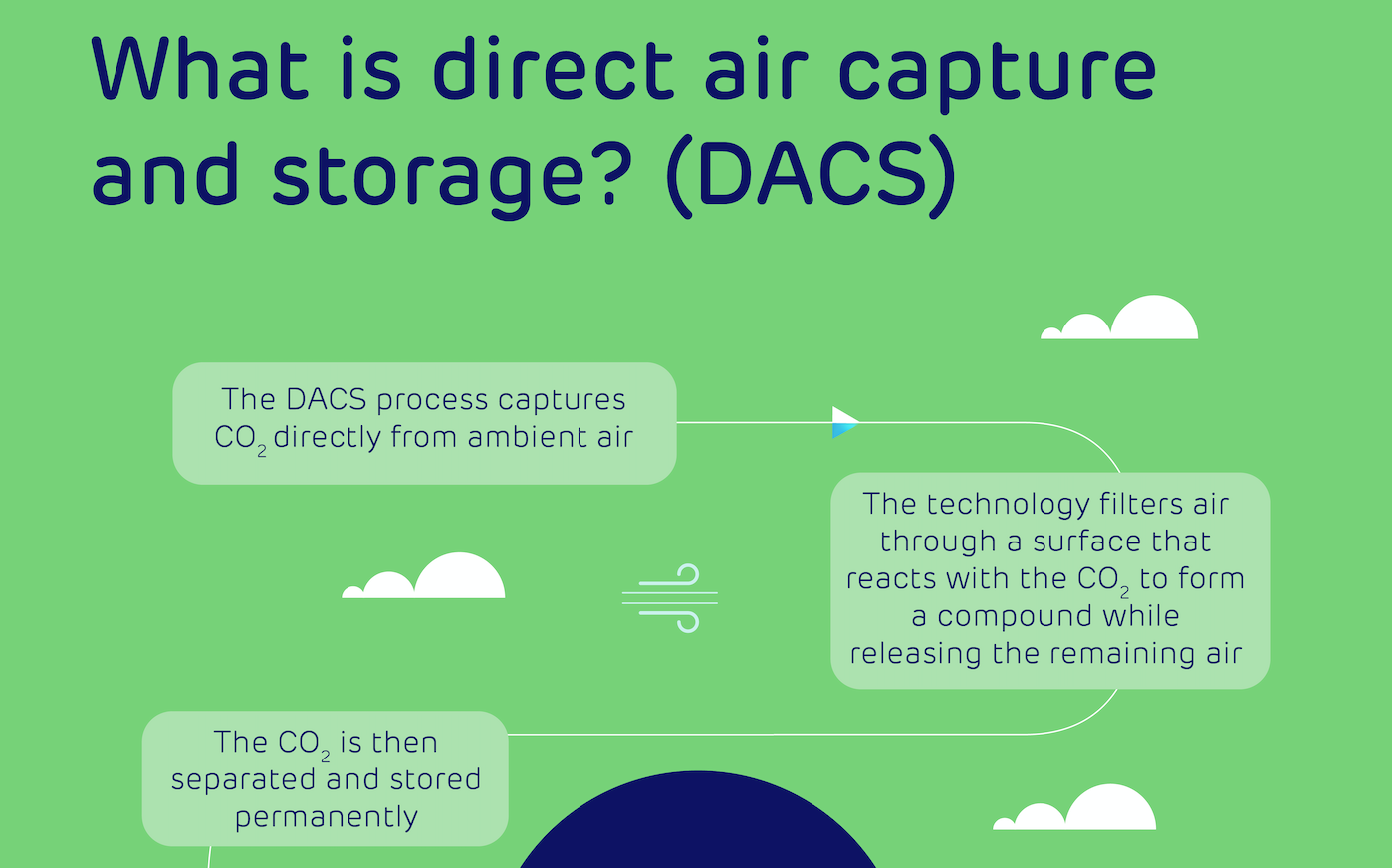

The project would see the addition of post combustion carbon capture to two of the existing biomass units, using sustainable biomass and technology from Drax’s technology partner, Mitsubishi Heavy Industries. Captured CO2 would be transported and permanently stored by the Group’s partners in the East Coast Cluster.

Vivid Economics concluded that it could deliver £370 million of economic benefit for the UK during construction, creating and supporting more than 10,000 jobs during peak construction.

Recent Baringa research also demonstrates that Drax is the UK’s largest source of energy security and will continue to play a vital role in the UK security of supply in to the late 2020s.

Drax aims to source 80% of materials and services for the project from British businesses and is also working with British Steel to explore opportunities for its UK production facilities to supply a proportion of the steel needed for BECCS.

A link to the Government’s announcement can be found here.

Enquiries:

Drax Investor Relations: Mark Strafford

Media:

Drax External Communications: Chris Mostyn

Attract innovation

Attract innovation