How do you get a drink in space? That was one of the challenges for NASA in the 1960s and 70s when its Gemini and Apollo programmes were first preparing to take humans into space.

The answer, it turned out, surprisingly lay in the electricity source of the capsules’ control modules. Primitive by today’s standard, these panels were powered by what are known as fuel cells, which combined hydrogen and oxygen to generate electricity. The by-product of this reaction is heat but also water – pure enough for astronauts to drink.

Fuel cells offered NASA a much better option than the clunky batteries and inefficient solar arrays of the 1960s, and today they still remain on the forefront of energy technology, presenting the opportunity to clean up roads, power buildings and even help to reduce and carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from power stations.

Power through reaction

At its most basic, a fuel cell is a device that uses a fuel source to generate electricity through a series of chemical reactions.

All fuel cells consist of three segments, two catalytic electrodes – a negatively charged anode on one side and a positively charged cathode on the other, and an electrolyte separating them. In a simple fuel cell, hydrogen, the most abundant element in the universe, is pumped to one electrode and oxygen to the other. Two different reactions then occur at the interfaces between the segments which generates electricity and water.

What allows this reaction to generate electricity is the electrolyte, which selectively transports charged particles from one electrode to the other. These charged molecules link the two reactions at the cathode and anode together and allow the overall reaction to occur. When the chemicals fed into the cell react at the electrodes, it creates an electrical current that can be harnessed as a power source.

Many different kinds of chemicals can be used in a fuel cell, such as natural gas or propane instead of hydrogen. A fuel cell is usually named based on the electrolyte used. Different electrolytes selectively transport different molecules across. The catalysts at either side are specialised to ensure that the correct reactions can occur at a fast enough rate.

For the Apollo missions, for example, NASA used alkaline fuel cells with potassium hydroxide electrolytes, but other types such as phosphoric acids, molten carbonates, or even solid ceramic electrolytes also exist.

The by-products to come out of a fuel cell all depend on what goes into it, however, their ability to generate electricity while creating few emissions, means they could have a key role to play in decarbonisation.

Fuel cells as a battery alternative

Fuel cells, like batteries, can store potential energy (in the form of chemicals), and then quickly produce an electrical current when needed. Their key difference, however, is that while batteries will eventually run out of power and need to be recharged, fuel cells will continue to function and produce electricity so long as there is fuel being fed in.

One of the most promising uses for fuel cells as an alternative to batteries is in electric vehicles.

Rachel Grima, a Research and Innovation Engineer at Drax, explains:

“Because it’s so light, hydrogen has a lot of potential when it comes to larger vehicles, like trucks and boats. Whereas battery-powered trucks are more difficult to design because they’re so heavy.”

These vehicles can pull in oxygen from the surrounding air to react with the stored hydrogen, producing only heat and water vapour as waste products. Which – coupled with an expanding network of hydrogen fuelling stations around the UK, Europe and US – makes them a transport fuel with a potentially big future.

Fuel cells, in conjunction with electrolysers, can also operate as large-scale storage option. Electrolysers operate in reverse to fuel cells, using excess electricity from the grid to produce hydrogen from water and storing it until it’s needed. When there is demand for electricity, the hydrogen is released and electricity generation begins in the fuel cell.

A project on the islands of Orkney is using the excess electricity generated by local, community-owned wind turbines to power a electrolyser and store hydrogen, that can be transported to fuel cells around the archipelago.

Fuel cells’ ability to take chemicals and generate electricity is also leading to experiments at Drax for one of the most important areas in energy today: carbon capture.

Turning CO2 to power

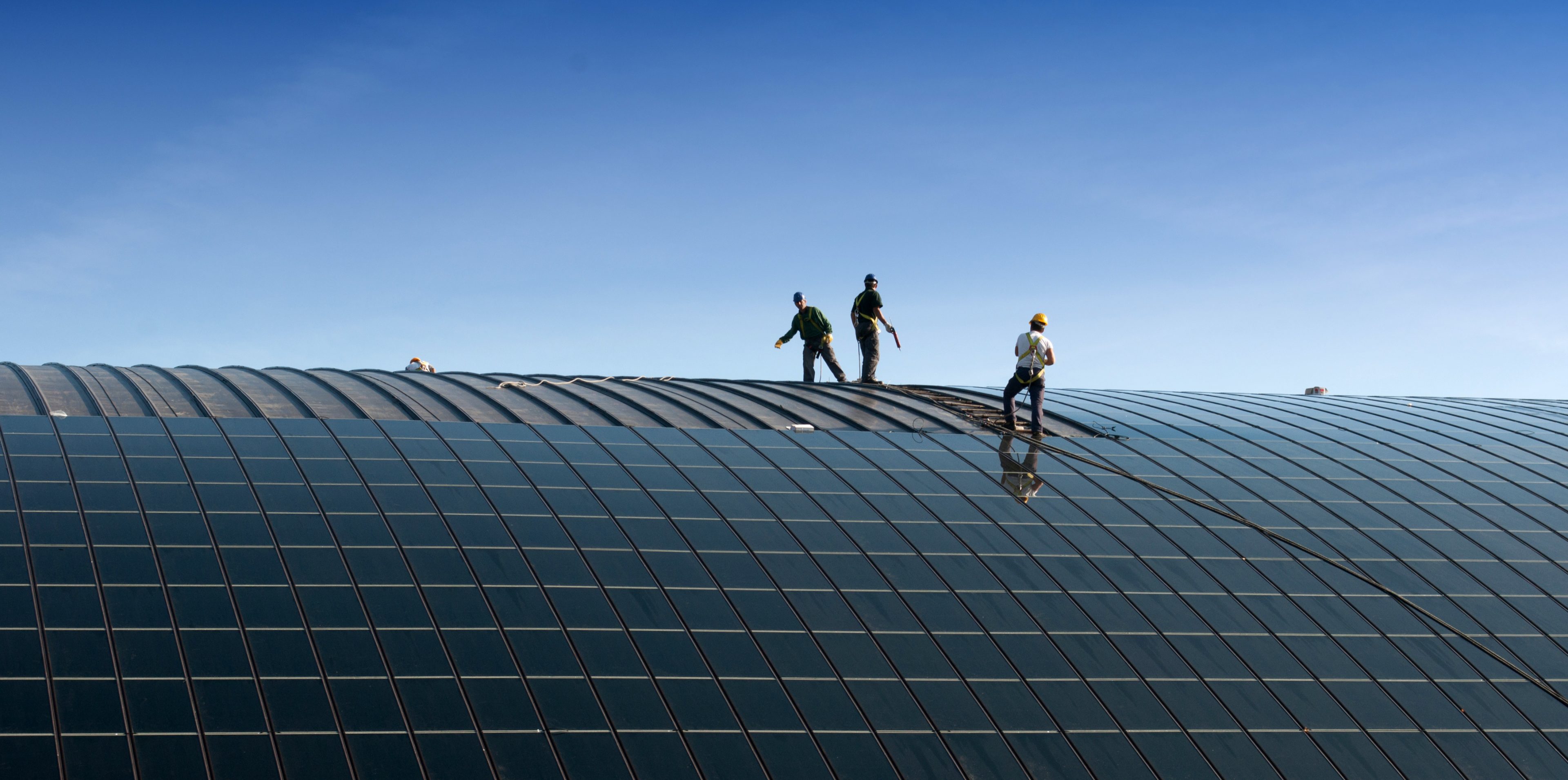

Drax is already piloting bioenergy carbon capture and storage technologies, but fuel cells offer the unique ability to capture and use carbon while also adding another form of electricity generation to Drax Power Station.

“We’re looking at using a molten carbonate fuel cell that operates on natural gas, oxygen and CO2,” says Grima. “It’s basic chemistry that we can exploit to do carbon capture.”

The molten carbonate, a 600 degrees Celsius liquid made up of either lithium potassium or lithiumsodium carbonate sits in a ceramic matrix and functions as the electrolyte in the fuel cell. Natural gas and steam enter on one side and pass through a reformer that converts them into hydrogen and CO2.

On the other side, flue gas – the emissions (including biogenic CO2) which normally enter the atmosphere from Drax’s biomass units – is captured and fed into the cell alongside air from the atmosphere. The CO2and oxygen (O2) pass over the electrode where they form carbonate (CO32-) which is transported across the electrolyte to then react with the hydrogen (H2), creating an electrical charge.

“It’s like combining an open cycle gas turbine (OCGT) with carbon capture,” says Grima. “It has the electrical efficiency of an OCGT. But the difference is it captures CO2 from our biomass units as well as its own CO2.”

Along with capturing and using CO2, the fuel cell also reduces nitrogen oxides (NOx) emissions from the flue gas, some of which are destroyed when the O2and CO2 react at the electrode.

From the side of the cell where flue gas enters a CO2-depleted gas is released. On the other side of the cell the by-products are water and CO2.

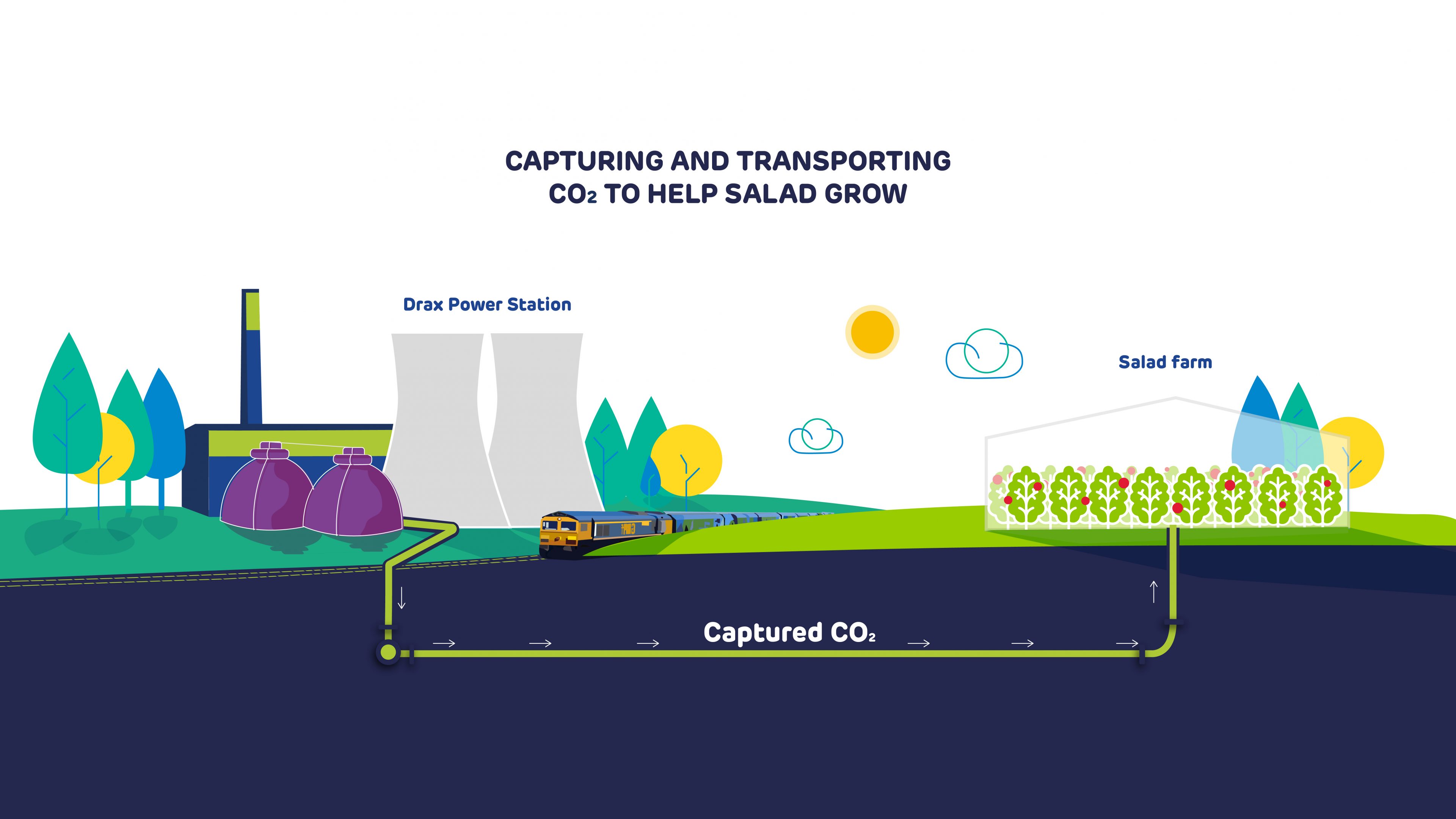

During a government-supported front end engineering and design (FEED) study starting this spring, this CO2 will also be captured, then fed through a pipeline running from Drax Power Station into the greenhouse of a nearby salad grower. Here it will act to accelerate the growth of tomatoes.

The partnership between Drax, FuelCell Energy, P3P Partners and the Department of Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy could provide an additional opportunity for the UK’s biggest renewable power generator to deploy bioenergy carbon capture usage and storage (BECCUS) at scale in the mid 2020s.

From powering space ships in the 70s to offering greenhouse-gas free transport, fuel cells continue to advance. As low-carbon electricity sources become more important they’re set to play a bigger role yet.

Learn more about carbon capture, usage and storage in our series:

- Planting, sinking, extracting – some of the ways to absorb carbon from the atmosphere

- From capture methods to storage and use across three continents, these companies are showing promising results for CCUS

- Why experts think bioenergy with carbon capture and storage will be an essential part of the energy system

- The science of safely and permanently putting carbon in the ground

- The numbers must add up to enable negative emissions in a zero carbon future, says Drax Group CEO Will Gardiner.

- The power industry is leading the charge in carbon capture and storage but where else could the technology make a difference to global emissions?

- A roadmap for the world’s first zero carbon industrial cluster: protecting and creating jobs, fighting climate change, competing on the world stage

- Can we tackle two global challenges with one solution: turning captured carbon into fish food?

- How algae, paper and cement could all have a role in a future of negative emissions

- How the UK can achieve net zero

- Transforming emissions from pollutants to products

- Drax CEO addresses Powering Past Coal Alliance event in Madrid, unveiling our ambition to play a major role in fighting the climate crisis by becoming the world’s first carbon negative company

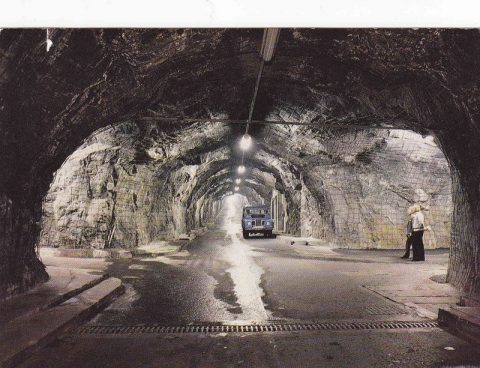

The access tunnel, cavern and the networks of passageways and chambers that make up the power station were all blasted and drilled by a workforce of 1,300 men in the

The access tunnel, cavern and the networks of passageways and chambers that make up the power station were all blasted and drilled by a workforce of 1,300 men in the  However, the reservoir also makes use of the aqueduct system made up of 19 kilometres of tunnels and pipes that covers 23 square kilometres of the surrounding landscape, diverting rainwater and streams into the reservoir. Calculating quite how much of the reservoir’s water comes from the surrounding area is difficult but estimates put it at around a quarter.

However, the reservoir also makes use of the aqueduct system made up of 19 kilometres of tunnels and pipes that covers 23 square kilometres of the surrounding landscape, diverting rainwater and streams into the reservoir. Calculating quite how much of the reservoir’s water comes from the surrounding area is difficult but estimates put it at around a quarter.