For the UK to reach net zero CO2 emissions by 2050 and do its part in tackling the biggest challenge of our time, all sectors of the economy must reduce their emissions and do it quickly.

I believe the best approach to tackling climate change is through ‘co-benefit’ solutions: solutions that not only have a positive environmental impact, but that are economically progressive for society today and in the future through training, skills and job creation.

As an energy company, this task is especially important for Drax. We have a responsibility to future generations to innovate and use our engineering skills to deliver power that’s renewable, sustainable and that doesn’t come at a cost to the environment.

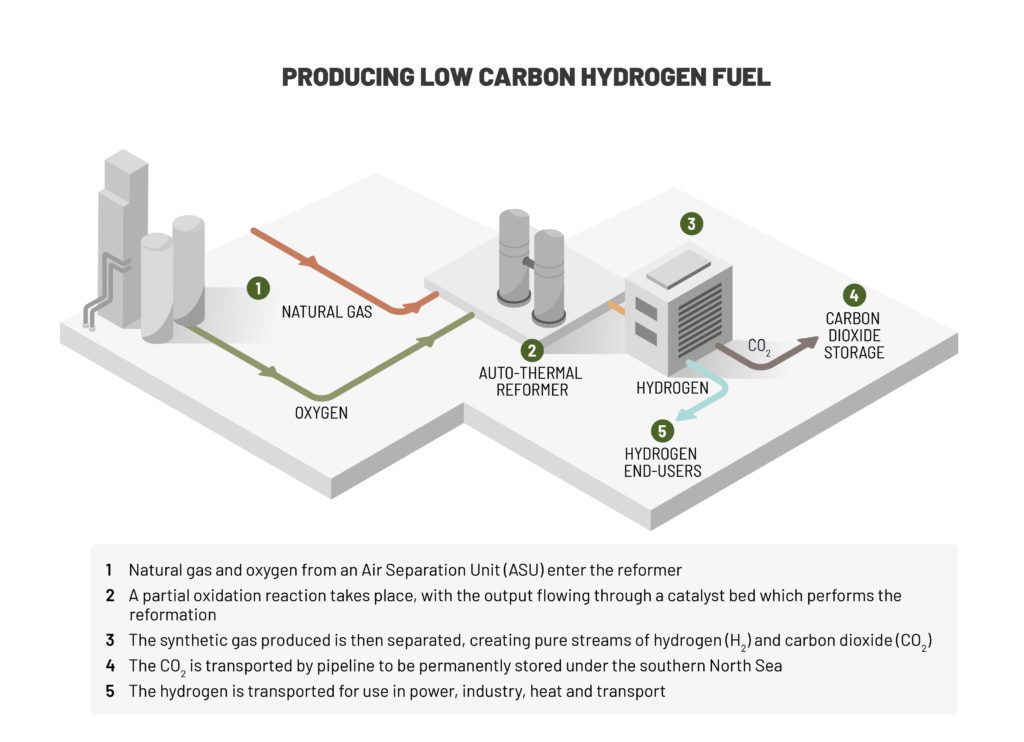

Our work on Zero Carbon Humber, in partnership with 11 other forward-thinking organisations, aims to deploy the negative emissions technology BECCS (bioenergy with carbon capture and storage), as well as CCUS (carbon capture, usage and storage) in industry and power, and ramp up hydrogen production as a low carbon fuel. These are all essential technologies in bringing the UK to net zero, but they are also innovative projects at scale that can benefit society and the lives of people in the Humber, and around the UK.

New jobs in a new sector

The Humber region has a proud history in heavy industries. What began as a thriving ship building hub has evolved to include chemicals, refining and steel manufacturing. However, these emissions-intensive industries have grown increasingly expensive to operate and many have left for countries where they can be run cheaper, leading to a decline in the Humber region.

If they are not decarbonised, these industries will face an even greater cost. By 2040, emitters could face billions of pounds per year in carbon taxes, making them less competitive and less attractive for international investment.

Deploying carbon capture and hydrogen are essential steps towards modernising these businesses and protecting up to 55,000 manufacturing and engineering jobs in the region.

Capturing carbon at Drax: Delivering jobs, clean growth and levelling up the Humber. Click to view executive summary and case studies from Vivid Economics report for Drax.

A report by Vivid Economics commissioned by Drax, found that carbon capture and hydrogen in the Humber could create and support almost 48,000 new jobs at the peak of the construction period in 2027 and provide thousands of long term, skilled jobs in the following decades.

As well as protecting people’s livelihoods, decarbonisation is also a matter of public health. In the Humber alone, higher air quality could save £148 million in avoided public health costs between 2040 and 2050.

I believe the UK is well position to rise to the challenge and lead the world in decarbonisation technology. There is a clear opportunity to export knowledge and skills to other countries embarking on their own decarbonisation journeys. BECCS alone could create many more jobs related to exporting the technology and operational know-how and deliver additional value for the economy. As interest in negative emissions grows around the world, the UK needs to move quickly to secure a competitive advantage.

A fairer economy

This is in many ways the start of a new sector in our economy – one that can offer new employment, earnings and economic growth. It comes at just the right time. Without intervention to spur a green recovery, the COVID-19 crisis risks subjecting long-term economic damage.

Being at the beginning of the industrial decarbonisation journey means we also have the power to shape this new industry in a way that spreads the benefits across the whole of the UK.

We’ve previously seen sector deals struck between the government and industry include equality measures. For example, the nuclear industry aims to count women as 40% of its employees by 2030, while offshore wind is committed to sourcing 60% of its supply chain from the UK.

Wind turbines at Bridlington, East Yorkshire

At present, the Humber region receives among the lowest levels of government investment in research and development in the UK, contributing to a pronounced skills gap among the workforce. In addition, almost 60% of construction workers across the wider Yorkshire and Humber region were furloughed as of August 2020.

A project such as Zero Carbon Humber could address this regional imbalance and offer skilled, long term jobs to local communities. That’s why I welcome the Prime Minister’s announcement of £1bn investment to support the establishment of CCUS in the Humber and other ‘SuperPlaces’ around the UK.

As the Government’s Ten Point Plan says, CCUS can ‘help decarbonise our most challenging sectors, provide low carbon power and a pathway to negative emissions’.

Healthier forests

The co-benefits of BECCS extend beyond our communities in the UK. We aim to become carbon negative by 2030 by removing our CO2 emissions from the atmosphere and abating emissions that might still exist on the UK’s path to net zero.

This ambition will only be realised if the biomass we use continues to be sourced from sustainable forests that positively benefit the environment and the communities in which we and our suppliers operate.

Engineer working in turbine hall, Drax Power Station, North Yorkshire

I believe we must continuously improve our sustainability policy and seek to update it as new findings come to light. We can help ensure the UK’s biomass sourcing is led by the latest science, best practice and transparency, supporting healthy, biodiverse forests around the world; and even apply it internationally.

Global leadership

Delivering deep decarbonisation for the UK will require collaboration from industries, government and society. What we can achieve through large-scale projects like Zero Carbon Humber is more than just the vital issue of reduced emissions. It is also about creating jobs, protecting health and improving livelihoods.

These are more than just benefits, they are the makings of a future filled with opportunity for the Humber and for the UK’s Green Industrial Revolution.

By implementing the Ten Point Plan and publishing its National Determined Contributions (NDCs) ahead of COP26 in Glasgow next year, the UK continues to be an example to the world on climate action.

The Humber has unique capabilities that positions it as a hub for developing all three.

The Humber has unique capabilities that positions it as a hub for developing all three.