Dear Prime Minister, Chancellor, COP26 President and Minister for Energy and Clean Growth,

We are a group of energy companies investing tens of billions in the coming decade, deploying the low carbon infrastructure the UK will need to get to net zero and drive a green recovery to the COVID-19 crisis.

We welcome the leadership shown on the Ten Point Plan for a Green Industrial Revolution, and the detailed work going on across government to deliver a net zero economy by 2050. We are writing to you to call on the Government to signal what this will mean for UK electricity decarbonisation by committing to a date for a net zero power system.

Head of BECCS Carl Clayton inspects pipes at the CCUS Incubation Area, Drax Power Station

The electricity sector will be the backbone of our net zero economy, and there will be ever increasing periods where Great Britain is powered by only zero carbon generation. To support this, the Electricity System Operator is putting in place the systems, products and services to enable periods of zero emissions electricity system operation by 2025.

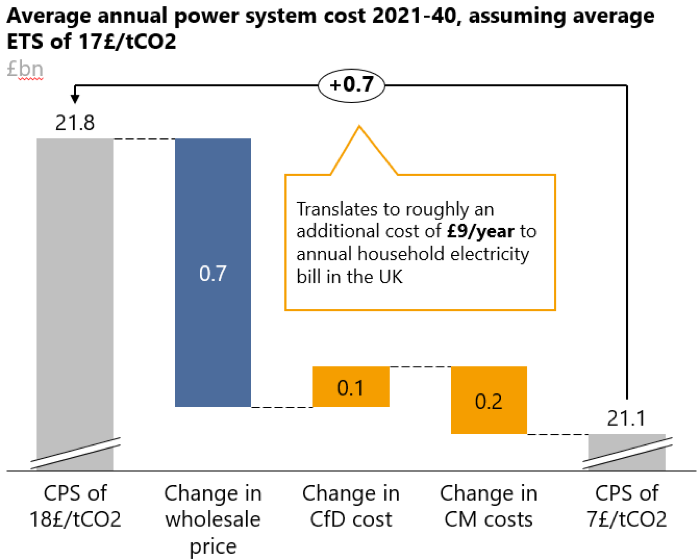

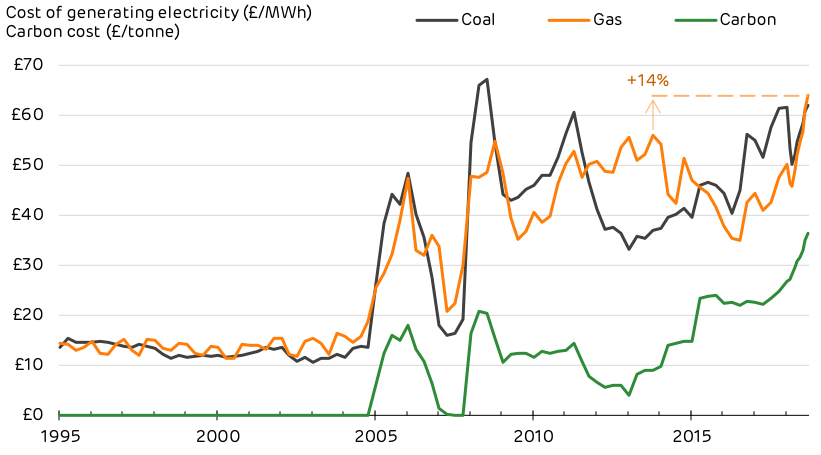

Achieving a net zero power system will require government to continue its efforts in key policy areas such as carbon pricing, which has been central in delivering UK leadership in the move away from coal and has led to UK electricity emissions falling by over 63% between 2012 and 2019 alone.

It is thanks to successive governments’ commitment to robust carbon pricing that the UK is now using levels of coal in power generation last seen 250 years ago – before the birth of the steam locomotive. A consistent, robust carbon price has also unlocked long term investment low-carbon power generation such that power generated by renewables overtook fossil fuel power generation for the first time in British history in the first quarter of 2020.

Yet, even with the demise of coal and the progress in offshore wind, more needs to be done to drive the remaining emissions from electricity as its use is extended across the economy.

In the near-term, in combination with other policies, continued robust carbon pricing on electricity will incentivise the continued deployment of low carbon generation, market dispatch of upcoming gas-fired generation with Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) projects and the blending of low carbon hydrogen with gas-fired generation. Further forward, a robust carbon price can incentivise 100% hydrogen use in gas-fired generation, and importantly drive negative emissions to facilitate the delivery of a net zero economy.

Next year, the world’s attention will focus on Glasgow and negotiations crucial to achieving our climate change targets, with important commitments already made by China, the EU, Japan and South Korea amongst others. An ambitious 2030 target from the UK will help kickstart the Sprint to Glasgow ahead of the UK-UN Climate Summit on 12 December.

Electricity cables and pylon snaking around a mountain near Cruachan Power Station, Drax’s flexible pumped storage facility in the Highlands

2030 ambition is clearly needed, but to deliver on net zero, deep decarbonisation will be required. Previous commitments from the UK on its coal phase out and being the first major economy to adopt a net zero target continue to encourage similar international actions. To build on these and continue UK leadership on electricity sector decarbonisation, we call on the UK to commit to a date for a net zero power system ahead of COP26, to match the commitment of the US President-elect’s Clean Energy Plan. To ensure the maximum benefit at lowest cost, the chosen date should be informed by analysis and consider broad stakeholder input.

Alongside near-term stability as the UK’s carbon pricing future is determined, to meet this commitment Government should launch a consultation on a date for a net zero power system by the Budget next year, with a target date to be confirmed in the UK’s upcoming Net Zero Strategy. This commitment would send a signal to the rest of the world that the UK intends to maintain its leadership position on climate and to build a greener, more resilient economy.

To:

- Rt Hon Boris Johnson MP, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

- Rt Hon Rishi Sunak MP, Chancellor of the Exchequer

- Rt Hon Alok Sharma MP, Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy and UNFCCC COP26 President

- Rt Hon Kwasi Kwarteng MP, Minister for Business, Energy and Clean Growth

Signatories:

BP, Drax, National Grid ESO, Sembcorp, Shell and SSE

View/download letter in PDF format

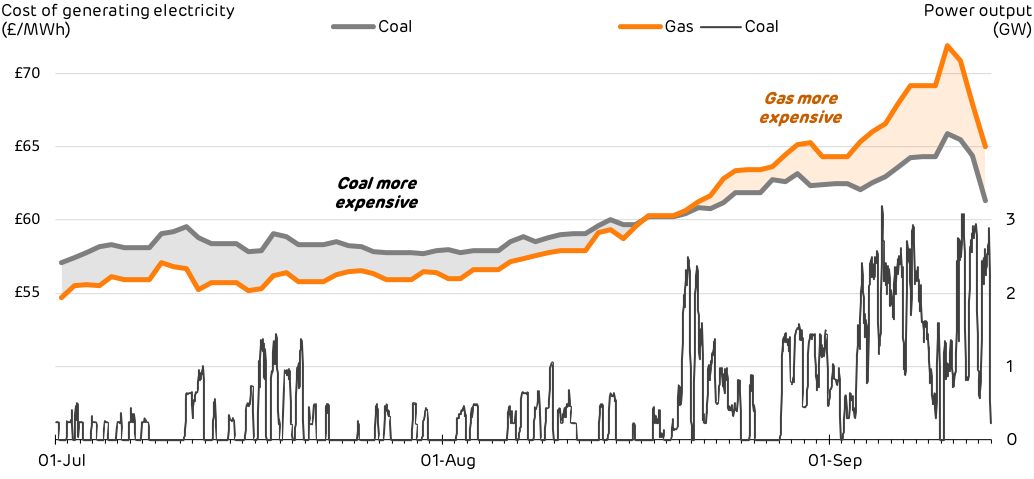

This Carbon Price Support has had a huge impact, particularly on coal. Prior to its introduction, coal represented 50% of power generation but since it has fallen to record lows. 2017 saw the first day without any coal on the power system since the industrial revolution. Records continue to be broken throughout 2018, with

This Carbon Price Support has had a huge impact, particularly on coal. Prior to its introduction, coal represented 50% of power generation but since it has fallen to record lows. 2017 saw the first day without any coal on the power system since the industrial revolution. Records continue to be broken throughout 2018, with