After a year of smashing renewable records, Great Britain’s electricity system is less dependent on fossil fuels than ever before. Over the course of 2017, low-carbon energy sources, including nuclear as well as renewables, accounted for half of all electricity production.

The finding comes from Electric Insights, a quarterly research paper on Britain’s power system, commissioned by Drax and written by researchers from Imperial College London. The latest report highlights how Great Britain’s electricity system is rapidly moving away from fossil fuels, with coal and gas dropping from 80% of the electricity mix in 2010 to 50% in 2017.

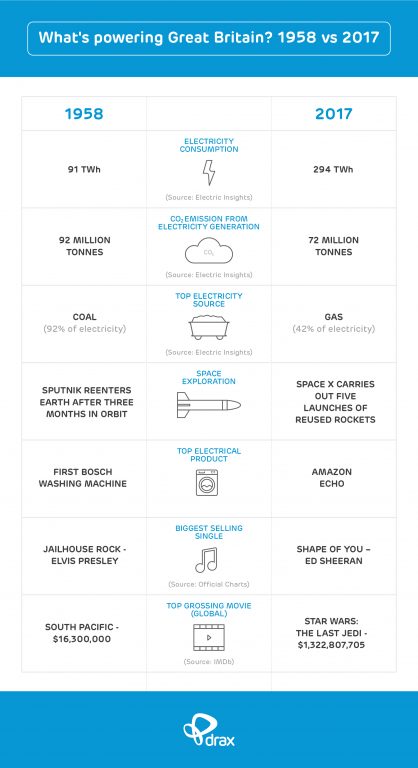

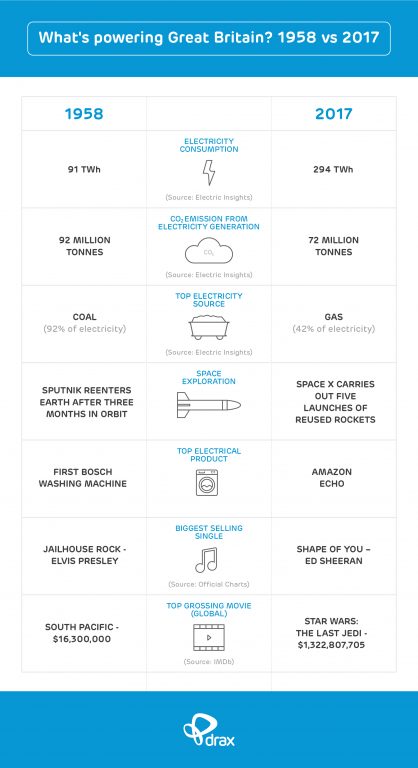

It’s an impressive change for eight years, but it’s even more dramatic when compared to 60 years ago.

Powering the past with renewables

In 2017 renewable output grew 27% over 2016 and produced 96 terawatt hours (TWh) of electricity – enough to power the entire country in 1958.

Back then Great Britain was dependent on one fuel: coal. It was the source of 92% of the country’s power and its high-carbon intensity meant emissions from electricity generation sat at 93 million tonnes of carbon dioxide (CO2). Compare that to just three million tonnes of CO2 emissions from roughly the same amount of power generated in 2017, just by renewables.

Today the electricity system is much more diverse than in 1958. In fact, with nuclear added to renewable generation, 2017’s total low-carbon capacity produced enough power to fulfil the electricity needs of 1964’s Beatlemania Britain.

But what’s enabled this growth in renewable generation? One answer, as Bob Dylan explained a year earlier, is blowin’ in the wind.

Read the full article here: Powering the past.

Stormy weather powering Great Britain

Wind power experienced a watershed year in 2017. Thanks to blusterier weather and a wave of new wind farm installations coming online, wind generation grew 45% between 2016 and 2017.

Windfarms, both onshore and offshore, produced 15% of the entire country’s electricity output in 2017, up from 10% in 2016. The 45 TWh it generated over the course of the year was almost double that of coal – and there’s potential for this to increase in 2018 as more capacity comes online.

The 1.6 gigawatts (GW) of new offshore wind turbines installed in Great Britain last year accounted for 53% of the net 3.15 GW installed across Europe. With large offshore farms at Dudgeon and Race Bank still being commissioned, the 3.2 GW of total new operating capacity registered in 2017 across offshore as well as onshore wind is on course to grow.

Co-author of the article, RenewableUK’s Head of External Affairs Luke Clark, said:

“These figures underline that renewables are central to our changing power system. Higher wind speeds and a jump in installed capacity drove a dramatic increase in the amount of clean power generated. Alongside breaking multiple records for peak output, wind energy continued to cut costs.”

As wind power is dependent on weather conditions, it is intermittent in its generation. But in 2017, more than one storm offered ideal conditions for wind turbines. During Q4 there were three named storms as well as the remnants of a hurricane all battering the British Isles, all of which helped push average wind speeds 5% higher than in 2016. While calculating wind power based on wind speed is complex, windier weather means more power – monthly average wind speed is proportional to monthly average power output from wind farms.

While the 2017 annual average wind speed of 10.1mph, was in line with the country’s long-term average, wind generation was not consistent across the year. In Q4 wind output was close to an average of 7 GW. By contrast, between May and August it was closer to 4 GW. Thankfully these calmer months saw longer hours of daylight, allowing solar power to compensate.

Read the full article here: Wind power grows 45%

Driving down carbon emissions

The knock-on effect of an increase in renewable generation is a drop in the carbon intensity of electricity production and in 2017 this reached a new low.

Across the year, carbon emissions, including those from imported sources, totalled 72 million tonnes, down 12% from 2016. This decrease is equal to 150 kg of CO2 saved per person, or taking 4.7 million cars off the roads. The least carbon intensive period of the quarter came just after midnight in the early hours of Monday 2 October, when it measured a record low of 56 grammes per kilowatt hour (g/kWh) thanks to low fossil fuel generation and high levels of renewables.

Over the whole year there were 139 hours when carbon intensity dipped below 100 g/kWh. This generally required 50% of the electricity mix to come from renewable sources and demand to be lower than 30 GW. For carbon intensity to dip under 100 g/kWh on a more permanent basis, greater renewable capacity will be required as demand rises.

Read the full article here: Carbon emissions down 12%

Interconnectors meeting future demand

Electricity demand in Great Britain has been on the decline since 2002, primarily due to more efficient buildings and appliances, and a decline in heavy manufacturing. However, this is expected to change over the coming years as more electric vehicles are introduced and the heating system is electrified to help meet 2050 carbon emissions targets.

While installing greater renewable capacity will be crucial in meeting this demand with low-carbon power, interconnectors will also play a significant role, particularly from France, which boasts a large nuclear (and low-carbon) capacity.

However, electricity sales through interconnectors are often based on day-ahead prices rather than the live market, which can lead to trades that aren’t reflective of demand on each sides of the channel.

In Q4 there were eight half-hours when demand was very high (more than 50 GW), yet power was being exported. This occurred despite day-ahead prices suggesting traders would lose money due to lower demand in France and the cost of using the interconnector. It highlights the need for improvements in inter-network trading as Great Britain increases its intermittent renewable generation and looks to a greater reliance on importing and exporting power.

Read the full article here: Moving electricity across the channel

Great Britain’s electricity system continues to break its renewable records each year and heading into 2018 this is likely to continue. Wind and solar power will continue to grow as more installations come online and a fourth coal unit at Drax will be upgraded to sustainable biomass, which could lead to another breakthrough year. Regardless, 2017 will be a tough one to beat.

Explore the data in detail by visiting ElectricInsights.co.uk

Commissioned by Drax, Electric Insights is produced independently by a team of academics from Imperial College London, led by Dr Iain Staffell and facilitated by the College’s consultancy company – Imperial Consultants.