The starting gun has fired and the challenge is underway. The government has officially set 2050 as the target year in which the UK will achieve carbon neutrality.

There’s no denying this economy-wide transformation will need a great deal of investment. Reaching net zero carbon emissions will require an evolutionary overhaul of not just Great Britain’s electricity system but the UK economy as a whole. And indeed, the way we live our lives and go about our business.

But that doesn’t mean it’s out of reach. Instead it will fall to technologies such as carbon capture usage and storage (CCUS), as well as bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS), to make it economical and possible.

The secret to making decarbonisation affordable

The UK’s Committee on Climate Change (CCC) estimates the price of decarbonisation will cost as little as 1% of forecast GDP per annum in 2050.

However, the Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) Select Committee inquiry found that failure to deploy CCUS and BECCS technology could double the cost to 2%. There are a number of reasons for this, such as the cost to jobs, productivity and living standards of shutting down industrial emitters. CCUS’s ability to contribute to a hydrogen economy can help avoid this.

Moreover, the CCC claims even with industries striving to decarbonise rapidly, as much as 100 megatonnes of hard-to-abate carbon dioxide (CO2) is expected to remain in the UK economy by 2050.

This makes carbon negative techniques and technologies, such as BECCS – which uses woody biomass that has absorbed carbon in its lifetime as forests – alongside direct air capture (DAC), the boosting of ocean plant productivity, much greater tree planting and better sequestration of carbon in soil, essential if the UK is to attain true carbon neutrality.

The importance of BECCS and CCUS in the zero carbon future is clear. Now is the time for rapid development. Not in 2030, not in 2040, but today in 2019 and into the 2020s.

But doing this requires the government to move beyond its historic policies that have failed to support the technology in the past. Progress needs long-term frameworks that provide private sector investors with the certainty they need to kick-start the commercial-scale deployment of CCUS technologies.

Laying down the tracks to negative emissions

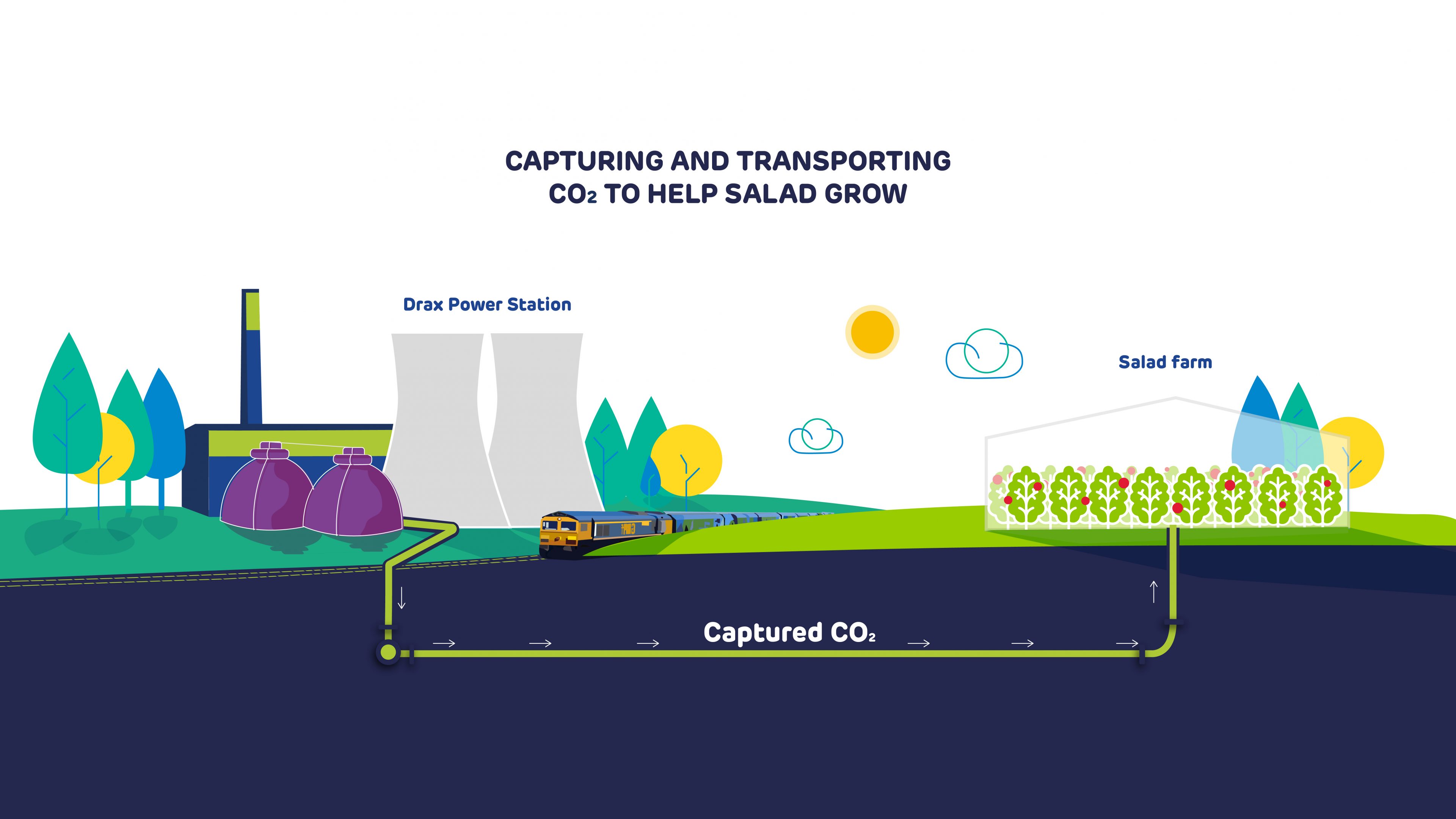

For carbon capture to become an integrated part of the energy system it must deliver value well beyond the energy sector. Establishing markets for products developed from captured carbon will play a role here, but to set the wheels in motion, financial frameworks are needed that can allow BECCS and CCUS to thrive.

One device that can allow the market to develop CCUS is the creation of contracts for difference (CfDs) for carbon capture. These currently exist in the low-carbon generation space, between generators and the government-owned Low Carbon Contracts Company (LCCC). Through these contracts, power generators are paid the difference between their cost of generating low carbon electricity (known as a strike price) and the price of electricity in Great Britain’s wholesale power market. If the power price in the market is higher than the strike price generators pay the difference back to the LCCC, meaning consumers are protected from price spikes too.

It means that the generator is protected from market volatility or big drops in the wholesale price of power, offering the security to invest in new technology. More than this, CfDs last many years meaning they transcend political cycles and the cost per megawatt can be reduced with a longer contract. Creating a market for carbon capture or negative emissions generation could offer the same security to generators to invest in the technology.

A CfD for BECCS should not only incentivise the building of infrastructure to capture carbon, but we must also recognise the valuable role that negative emissions can play. By compensating BECCS producers for their negative emissions, it should provide a lower cost alternative to reducing all other CO2 emissions to zero, while still ensuring that the UK can get to net zero.

Beyond installing carbon capture at existing generation sites, one of the major financial barriers to the wider deployment of CCUS and BECCS is the cost and liability associated with transporting and storing captured carbon.

A Regulated Asset Base (RAB) funding model, would encourage investment by gradually recovering the costs of transport and storage via a regulated return. This approach is currently under consideration as a means of financing other major infrastructure projects.

A RAB allows businesses, including investment and pension funds, to invest in projects under the oversight of a government regulator. In exchange for their commitment, investors can collect a fee through regular consumer and non-domestic bills.

Led by industry; guided by government

Ultimately, the current carbon trading system is based around charging polluters. But as we approach a post-coal UK and in order to achieve net zero, it’s necessary for this to evolve – from economically disincentivising emissions to incentivising carbon-negative power generation.

However, with the cost of carbon capture and negative emissions differing between types of industries and technologies, there’s a requirement to consider differentiated carbon prices to guide industry through long-term strategy. But the need for carbon capture development is too pressing for us as an industry to wait.

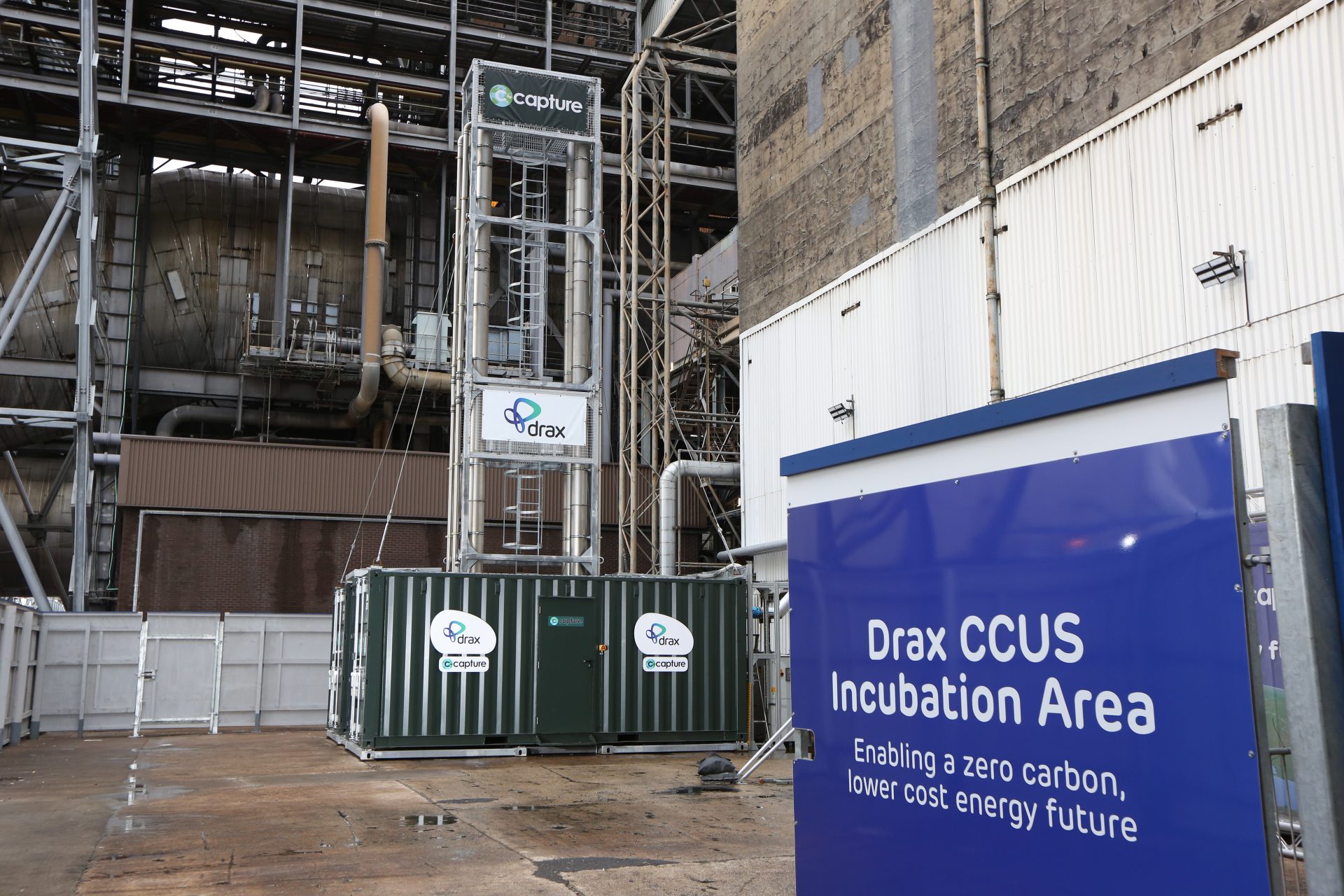

At Drax Power Station our BECCS pilot is just the beginning of our wider ambitions to become the first negative emissions power station. Our use of biomass already makes Drax Power Station the largest generator of renewable electricity in Great Britain. The responsibly-managed working forests our suppliers source from absorbed carbon from the atmosphere as they grew so adding carbon capture at scale to this supply chain can turn our operation from low carbon, to carbon-neutral and eventually carbon negative.

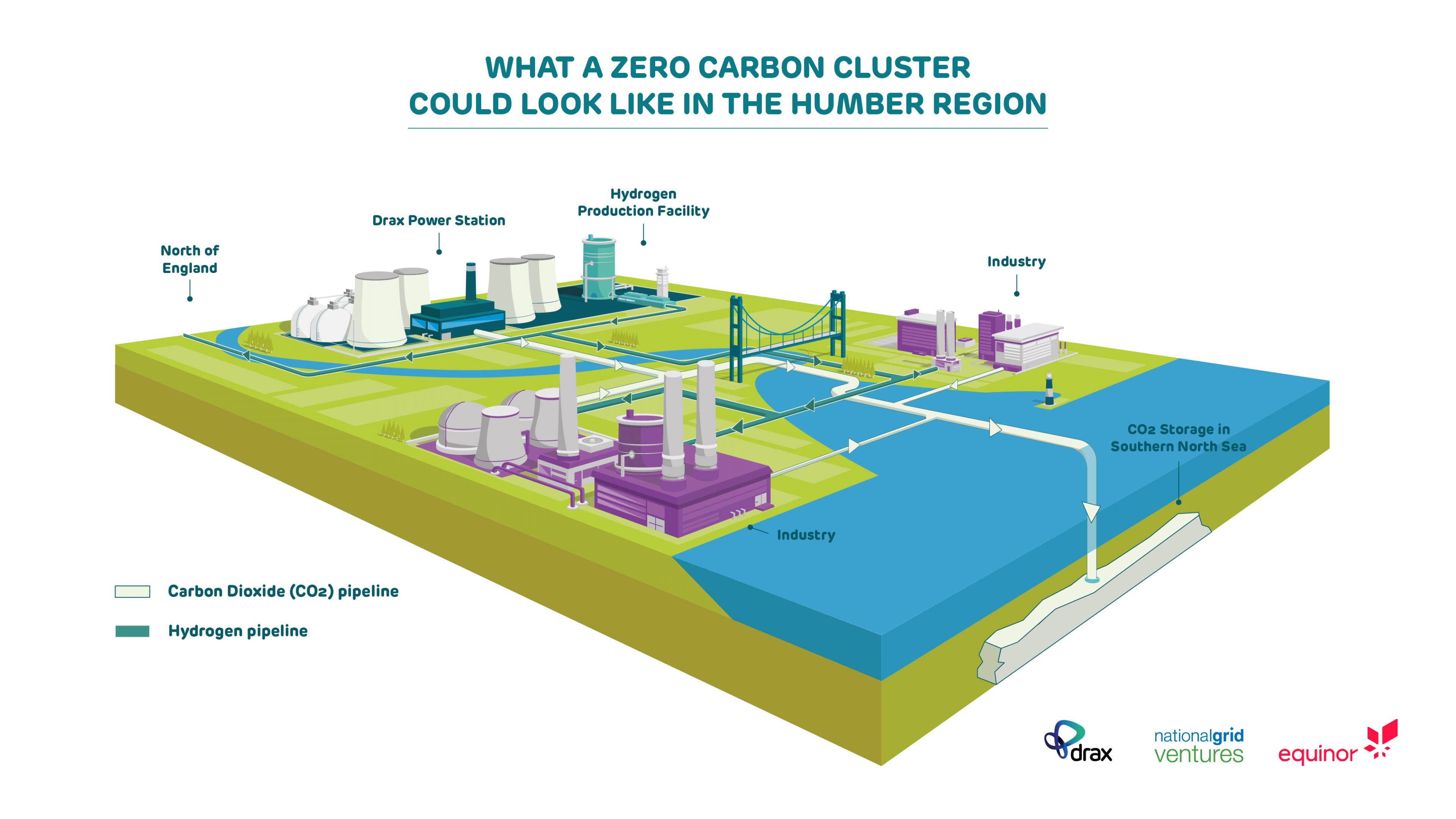

And we have bigger plans still to create a net zero carbon industrial cluster in the Humber region, in partnership with Equinor and National Grid. The cluster would deliver carbon capture at the scale needed to not just decarbonise the most carbon-intensive industrial region in the UK, but to put the country at the forefront of the decarbonisation of industry and manufacturing.

Government action is needed to make CCUS and BECCS economically sustainable at scale as an integrated part of our energy system. However, the onus is on us, the energy industry to lead development and act as trusted partners that can deliver the decarbonisation needed to reach net zero carbon by 2050.

Learn more about carbon capture, usage and storage in our series:

- Planting, sinking, extracting – some of the ways to absorb carbon from the atmosphere

- From capture methods to storage and use across three continents, these companies are showing promising results for CCUS

- Why experts think bioenergy with carbon capture and storage will be an essential part of the energy system

- The science of safely and permanently putting carbon in the ground

- The power industry is leading the charge in carbon capture and storage but where else could the technology make a difference to global emissions?

- From NASA to carbon capture, chemical reactions could have a big future in electricity

- A roadmap for the world’s first zero carbon industrial cluster: protecting and creating jobs, fighting climate change, competing on the world stage

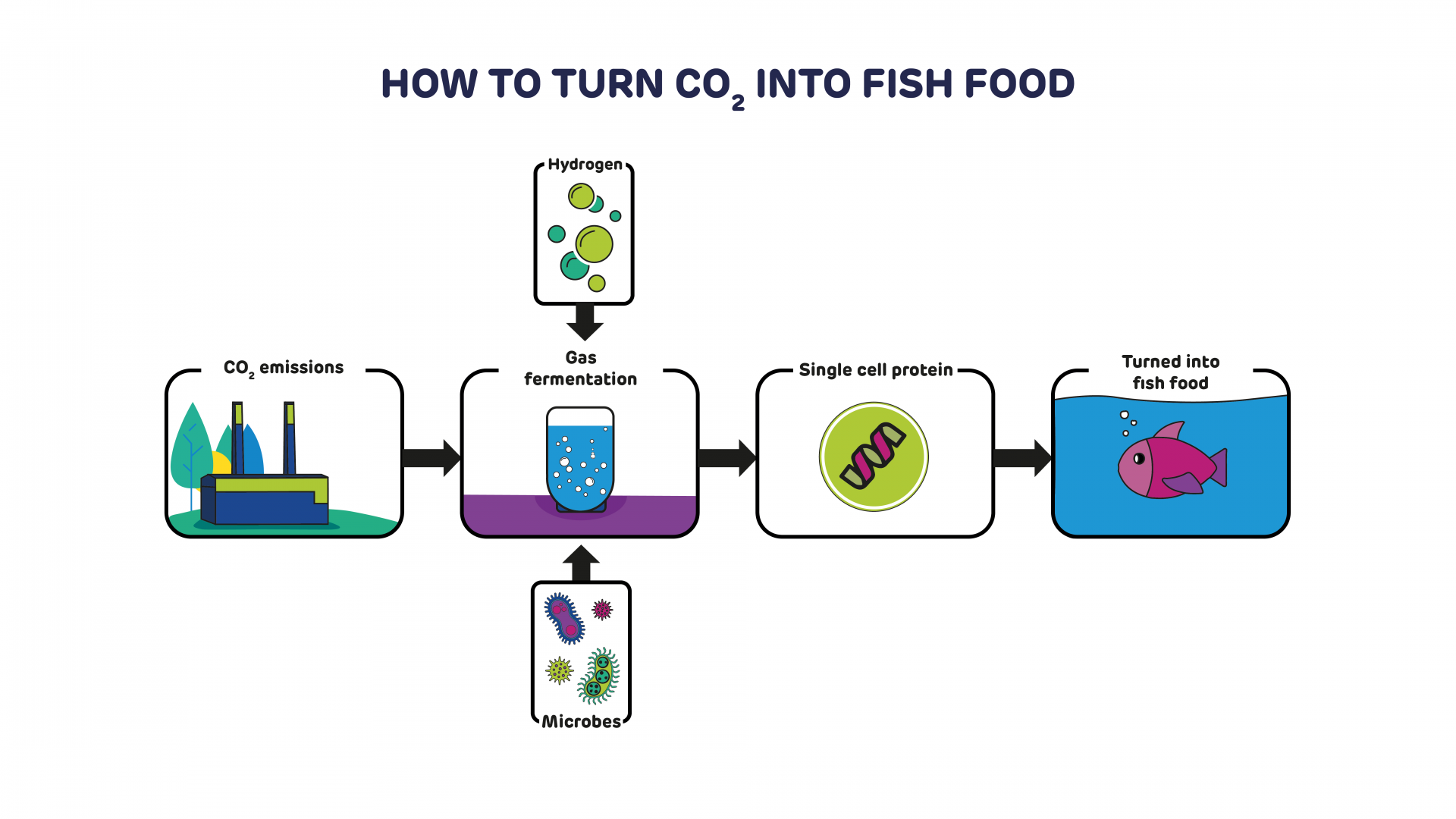

- Can we tackle two global challenges with one solution: turning captured carbon into fish food?

- How algae, paper and cement could all have a role in a future of negative emissions

- How the UK can achieve net zero

- Transforming emissions from pollutants to products

- Drax CEO addresses Powering Past Coal Alliance event in Madrid, unveiling our ambition to play a major role in fighting the climate crisis by becoming the world’s first carbon negative company

Burning waste and growing algae

Burning waste and growing algae Fully integrating BECCS into biomass power

Fully integrating BECCS into biomass power

Plants absorbing CO2 through photosynthesis is the most-commonly known part of the carbon cycle, however, rocks also absorb CO2 as they weather and erode.

Plants absorbing CO2 through photosynthesis is the most-commonly known part of the carbon cycle, however, rocks also absorb CO2 as they weather and erode.

Alongside this, our plans to repower the last of our coal-fired units to highly-efficient combined cycle gas turbines (CCGT) and build four, rapid-response open cycle gas turbines (OCGT) will give the electricity system the

Alongside this, our plans to repower the last of our coal-fired units to highly-efficient combined cycle gas turbines (CCGT) and build four, rapid-response open cycle gas turbines (OCGT) will give the electricity system the