Picture an airship. Massive and slow moving, it makes its way across skies. It’s a far cry from what we’ve come to expect from the speed and innovation of today’s air transport.

But go back a century and airships were not only the height of technology, they were also a key part of Britain’s aerial war effort.

Part of this innovation can be traced back to the Yorkshire village of Barlow, which was the site of a factory that built the vessels during the First World War. Three riged-structure airships where constructed and took flight during the factory’s history and this October marks the centenary of the first airship flight at the site in 1917.

This is the story of how a stretch of land by the small Yorkshire village near Selby became the frontline for innovation in British military aviation.

The Admiralty marches in

During the First World War, the German zeppelin fleet posed a very real threat to the people of Britain. More reliable than the aeroplanes of the time, hydrogen-filled airships’ ability to hold heavy loads and remain airborne for periods of 20-plus hours allowed them to carry out strategic bombing campaigns.

While the actual effectiveness of these raids on the UK mainland remains questionable, the psychological impact of the zeppelins’ abilities to attack UK cities pushed the military to respond. In early 1916, at the request of the Admiralty, the Armstrong-Whitworth Airship Department was formed to build zeppelin-style aircraft.

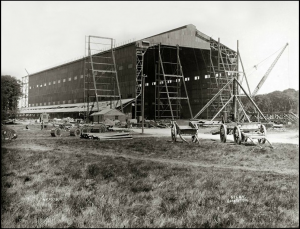

To set about constructing the airship, Armstrong-Whitworth acquired a large area of ground in Barlow village. Within six months of the initial Admiralty instructions, the airship shed was completed. It was the start of a century of industrial innovation in the area.

Changing the area

Up until the beginning of the 20th century, Barlow was almost exclusively agricultural, but the construction of the Selby-Goole railway line changed that. It suddenly connected the area as never before and enabled Armstrong-Whitworth to establish the 880-acre airship facility.

Along with a 700-foot shed, the site also included workshops, offices, living quarters for the workers and managers, and eight huge mooring blocks for the airships. It was an immediate change to the landscape, but it had a greater impact than just its physical footprint. Between 1911 and 1951 Barlow saw a 36% population increase – thought to be a result of the new military presence.

The First World War also began to change the demographics of the area. With more than 2 million men conscripted into the army during the conflict, women began to take up the traditionally male-held industrial jobs. When the war ended in November 1918, Armstrong-Whitworth employed 1,500 people – over 1,000 of those were women.

The airships take flight

Four airships were constructed over Barlow’s lifetime as a military facility, three of which made it to the air:

-

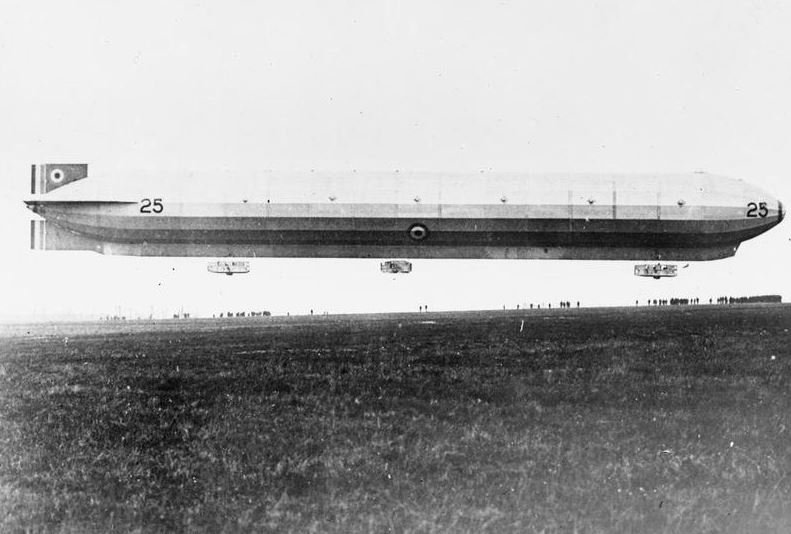

25r

The 25r first took flight on 14 October 1917, but it encountered problems from the start. In the same manner as its predecessor the 23r, the craft did not have enough lift in trials. Subsequently, dynamos, bomb gear and furniture where stripped out to reduce the weight enabling the ship to make its first flight.

Despite later stability issues, the 25r served between December 1917 and September 1919, clocking up more than 221 hours of flight time and covering almost 9,500 kilometres.

-

R29

Armstrong-Whitworth’s next aircraft would prove to be one of Britain’s most successful riged-framed airships. Commissioned on 20 June 1918, the R29 flew for 335 hours and covered more than 13,000 kilometres in its five-month operational career.

During this time the R29 encountered German U-boats on three occasions. While the first escaped, the second struck a mine when pursued by the airship. The R29 attacked and destroyed a third U-boat off the coast of Northumberland in September 1918, dropping two 100 kilogram bombs on the UB115 submarine and recording the only success of any British wartime riged airship.

-

R33

Designs for the R33 were well underway by September 1916, when the German L33 zeppelin was brought down in Essex while on a London-bombing raid. Despite the crew’s efforts to destroy the airship, it fell into British hands virtually intact, offering a trove of potential secrets.

Adapted with the information learned from the downed L33, the R33 was eventually completed after the November 1918 armistice, but nevertheless went on to operate for 10 years – longer than any other British riged airship.

Used with the kind permission of the Airship Heritage Trust

Taking flight for the first time on 6 March 1919, the R33 was initially used to promote ‘Victory Bonds’ around the country before being demilitarised.

Famously, the R33 was torn from its mast at Pulham in a gale and blown out over the North Sea. It took a partial crew 28 hours to eventually steer the damaged airship back to Pulham.

From military camp to nature reserve

Following the First World War, the land around Barlow was sold off to civilian firms until 1938 when the then-named ‘War Department’ took over the area to set up an army ordnance and command supply depot.

By the 60s, however, the UK’s need for military manufacturing had reduced. Instead, with increasing demand for power and rich coal seams found there, Barlow and the surrounding area became the site of what would become the UK’s biggest power station: Drax. Construction of Drax Power Station began exactly 50 years after the first Barlow airship took flight – and half a century ago from the present day.

Barlow Mound, which held the airship construction facility, is now a unique nature reserve under which Drax Power Station can safely store the ash created from generating power.

And while airships may seem like relics of a long-gone era of British skies, the vessels could be on the verge of a resurgence. The British-built Airlander 10 – an airship-aeroplane hybrid – is the longest aircraft in the world and recently received the green light from the European Aviation Safety Agency to start carrying out customer trials and demonstrations.

It can now fly at an elevation of 2,136m, up to 50 knots and 75 nautical miles away from its Bedfordshire airfield (which is located around eight miles from the proposed site of Millbrook Power, a Drax rapid response gas project). Perhaps a new golden era is on the horizon for British airships.