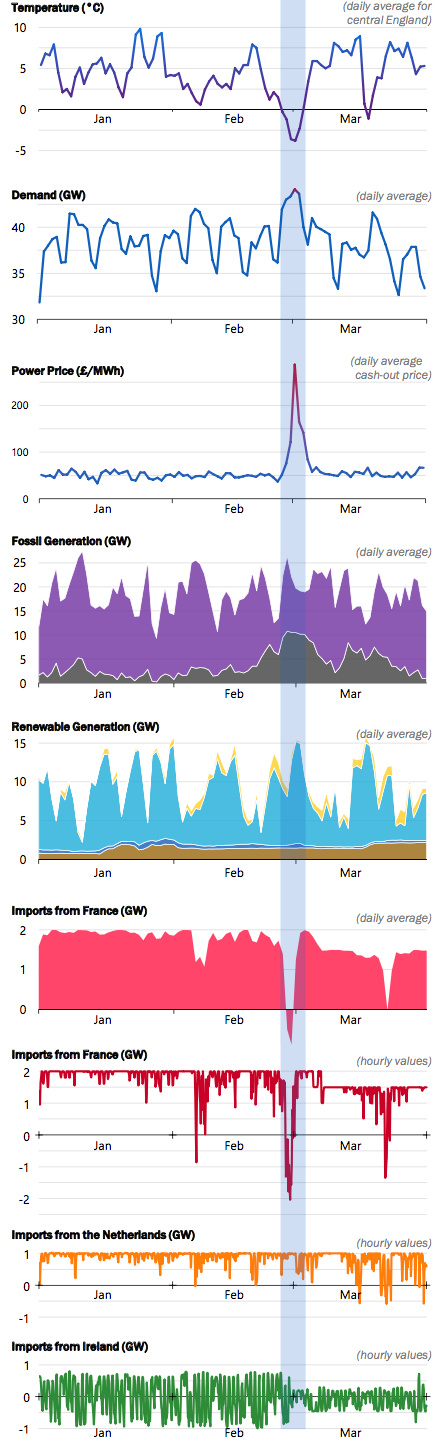

Thursday 1 March was the coldest spring day on record, averaging –3.8°C. The six days from 26 February to 3 March (highlighted in blue) were the coldest Britain has been since Christmas 2010.

Thursday 1 March was the coldest spring day on record, averaging –3.8°C. The six days from 26 February to 3 March (highlighted in blue) were the coldest Britain has been since Christmas 2010.

This pushed electricity demand up 10%, as people used more electric heating to keep warm. The evening peak demand on 1 March was the highest in three years, and so was not stretching the system to its limits.

Electricity prices rose to five times the average for the quarter. They peaked at £990 per megawatt hour (MWh) for half an hour, and also fell to –£150 per MWh as the market became volatile.

Coal generation surged for the weeks surrounding the cold spell. Not because more output from conventional plants was needed, but rising gas prices made it more economical to burn than gas. Total generation from fossil fuels remained around 20–25 GW.

Biomass and hydro ran solidly throughout the cold spell. Wind output was particularly high when it was most needed, ranging from 11.8 to 13.8 GW during 1 March. Whilst wind certainly helped, the lights would not have gone off without it, as up to 19 GW of spare gas capacity was available if needed.

Britain’s links to other countries were not so helpful. We exported to France through much of the cold spell. French electricity demand is more impacted by temperature than British, as more French homes use electric heating.

Looking in more detail at the UK’s links to other countries:

- Britain had been largely importing from France all year, but then exported solidly through 27–28 February, when power prices were higher in France.

- Prices remained lower in the Netherlands, so Britain continued importing from them.

- Britain and Ireland traded power back and forth to help balance their systems. On 3 March the East-West link between North Wales and Dublin was taken offline for (unrelated) maintenance.