https://www.drax.com/ca/investors/disclaimer-proposed-acquisition-of-pinnacle-renewable-energy-inc-by-drax/

https://www.drax.com/ca/investors/disclaimer-proposed-acquisition-of-pinnacle-renewable-energy-inc-by-drax/

The eigth report in a series of catchment area analyses for Drax looks at the fibre sourcing area surrounding two compressed wood pellet plants operated by Pinnacle.

This part of interior British Columbia (BC) is unique in the Drax supply chain. Forest type, character, history, utilisation, natural challenges, logistics, forest management and planning are all very different to the other regions from which Drax sources biomass. Recently devasted by insect pest and fire damage, Arborvitae Environmental Services has produced a fascinating overview of the key issues and challenges that are being experienced in this region.

Like the entire BC Interior, the area has suffered a devastating attack of Mountain Pine Beetle (MPB) damage over the last 20 years which has completely dominated every forest management decision and action. Within the catchment area, the MPB killed an estimated 157 million cubic metres (m3) between 1999 and 2014, representing 42% of the estimated 377 million m3 of total standing timber in the catchment area in 1999. In addition, severe wildfires in 2018 burned an estimated 7.1 million m3.

These natural events have had a devastating impact on the forest resource. Harvesting increased significantly to utilise the dead and dying timber as lumber in sawmills whilst it was still viable.

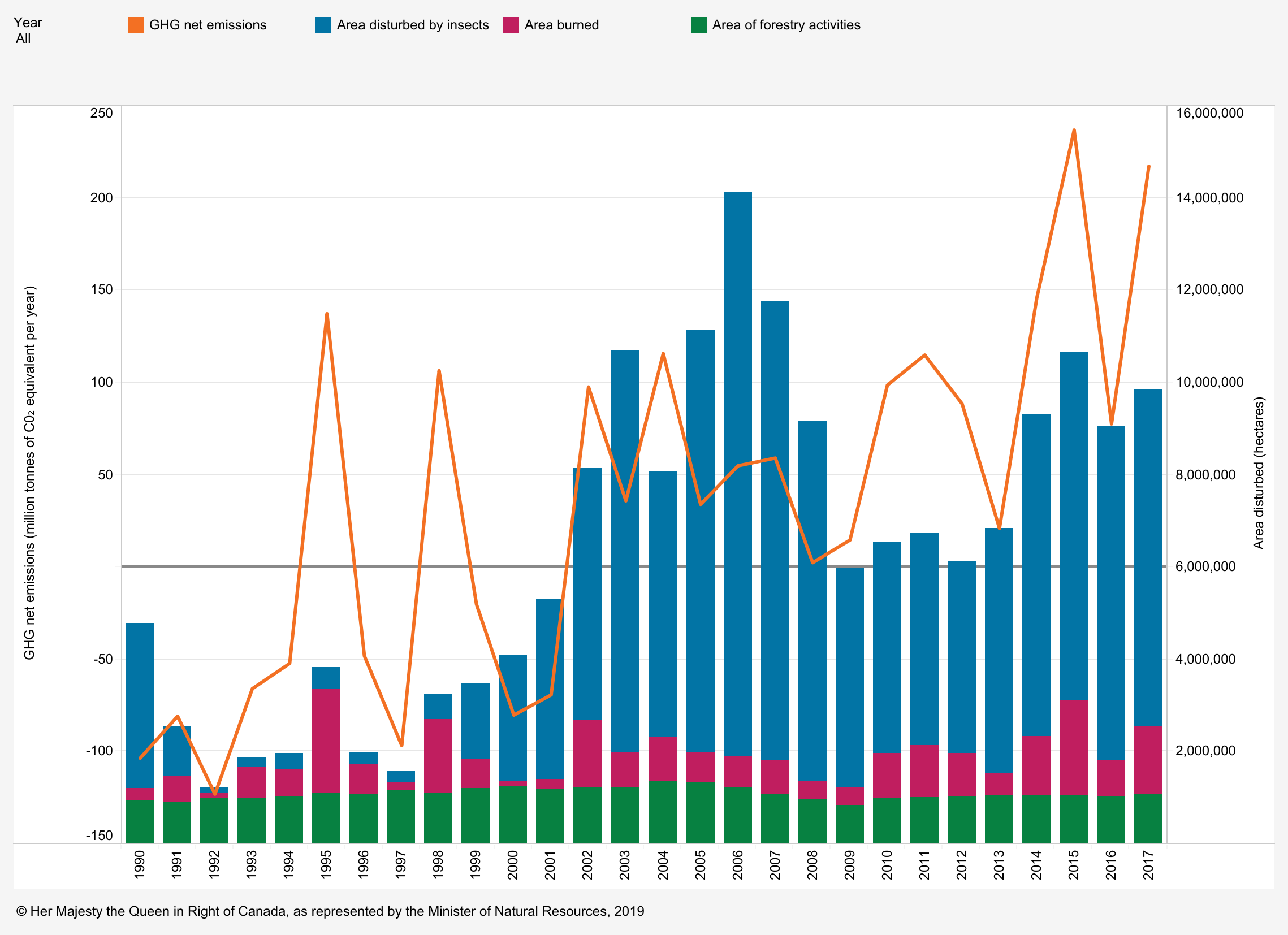

Net carbon emissions in Canada’s managed forest: All areas, 1990–2017; illustrates that the impact of fires and insect damage have been far more significant, by hectares affected, than forestry activity; Chart via Natural Government of Canada

The Pinnacle pellet mills at Burns Lake and Houston were established alongside the sawmills to utilise the sawmill residues as there were no other viable markets for this material. These sawmills draw fibre from a large distance, up to 300 miles away. Therefore, the size of the catchment area in this piece of analysis is determined by the sourcing practices of the sawmills rather than the economic viability of low grade roundwood transport to the pellet mill (see Figure 1).

Damage to pine trees by Mountain Pine Beetle (MPB)

The two mills producing high-density biomass pellets have provided an essential outlet for residue material that would otherwise have no other market and until very recently were supplied almost entirely by mill residuals. As the quantity of dead and dying timber has reduced and sawmill production has declined, the pellet mills are beginning to utilise more low-grade roundwood and forest residues (that are otherwise heaped and burned at roadside following harvest) to supplement the sawmill co-products.

The total land area in the catchment for Burns Lake and Houston is 4.47 million hectares (ha) of which 3.75 million ha is classed as forest land, 94% of the catchment area is public land under provincial jurisdiction. The provincial forest service is responsible for all decisions on land use and forest management on public land, in consultation with communities and indigenous groups, determining which areas are suitable for timber production and which areas require protection. Approximately 34% of the catchment area is not available for commercial timber harvesting because it is either non-forested or it has low productivity, and other operational challenges, or it is protected for ecological and wildlife reasons.

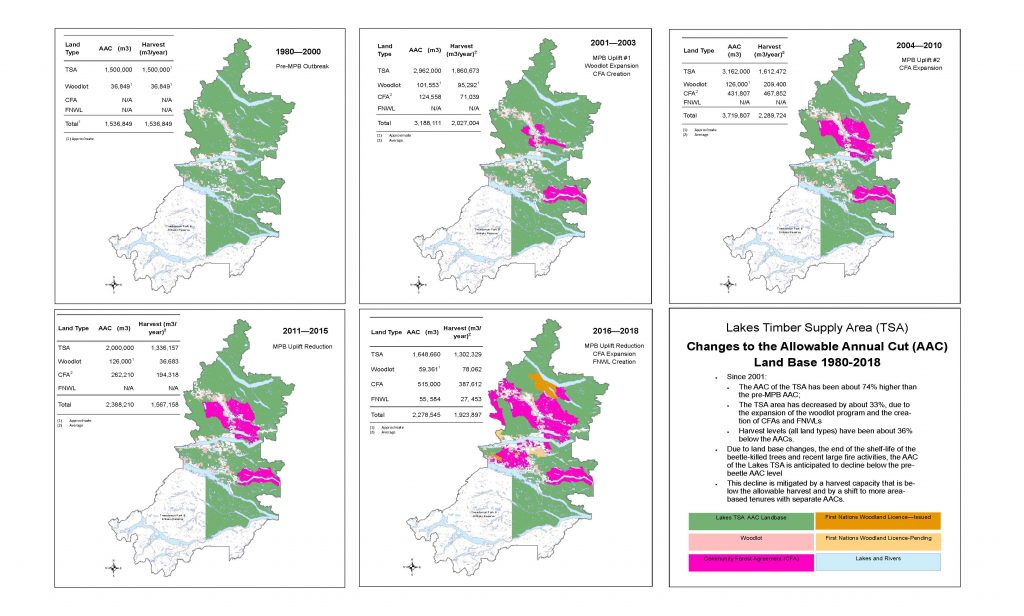

The Chief Forester for the province sets the Annual Allowable Cut (AAC) which determines the quantity of timber that can be harvested each year. Ordinarily this will be based on the sustainable yield capacity of the working forest area, but in recent years the MPB damage has necessitated a significant increase in AAC to facilitate the salvage of areas that have been attacked and damaged (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Changes in Annual Allowable Cut 1980 to 2018 (Source: Nadina District FLNRORD) [Click to view/download]

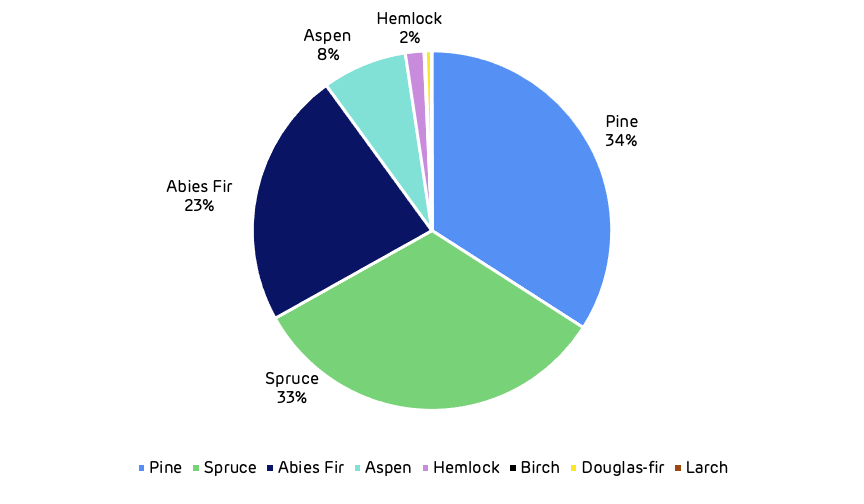

The forest area is dominated by coniferous species (see Figure 3) predominantly lodgepole pine, spruce and fir (90% of the total area), with hardwood species (primarily aspen) making up just 8% of the total area.

Figure 3: Species composition of forest land in the catchment area.

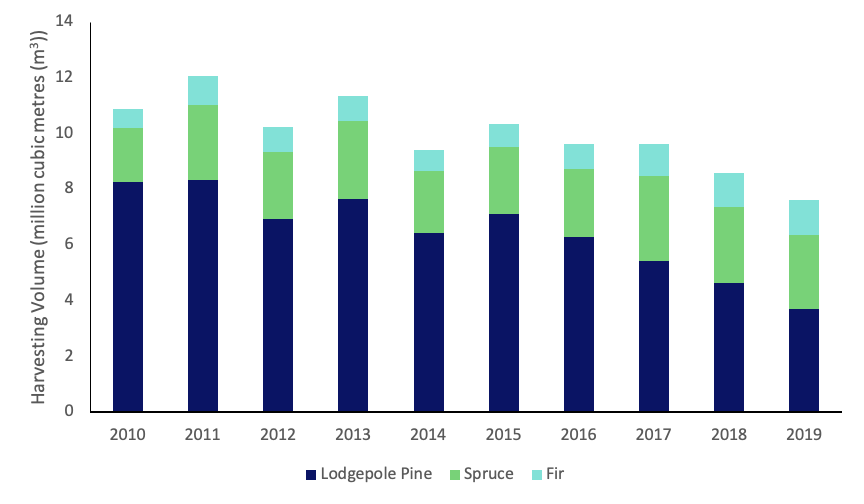

The annual harvest volume was at a peak in the early part of the last decade at over 12 million m3 in 2011. This has now declined by around 4.5 million m3 in 2019 (see Figure 4) as the beetle damaged areas are cleared and replanted. The AAC and harvesting levels are expected to be reduced in the future to allow the forest to regrow and recover.

Figure 4: Annual change in harvest volume of major species

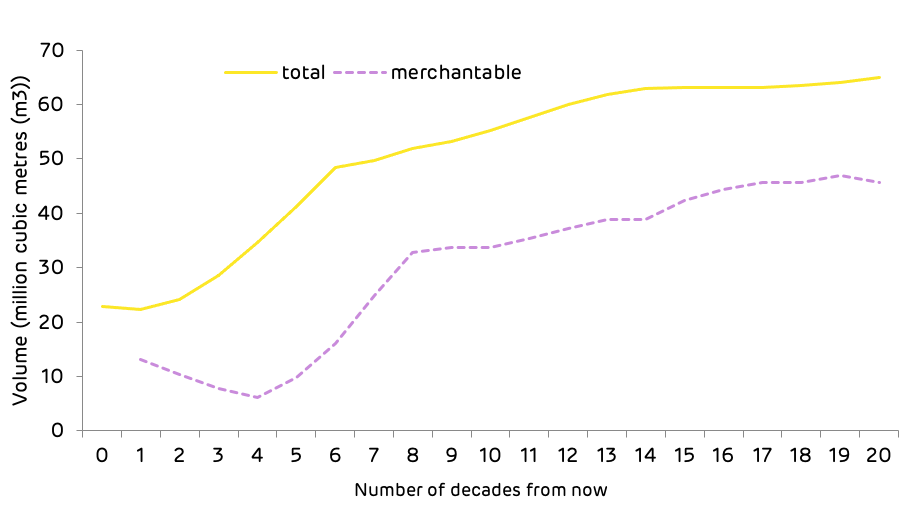

Historically, the forest area has naturally regenerated with self-seeded stands reaching a climax of mature pine, spruce, and Abies fir mixtures. As the forest matured, it would often be subject to natural fires or other disturbance which would cause the cycle to begin again. Following the increase in harvesting of beetle damaged areas, many forests are now replanted with mixtures of spruce and pine rather than naturally regenerated. This is likely to lead to an increase in forest growth rates in the future and a higher volume of timber availability once the areas reach maturity (see Figure 5).

Figure 5: Forecast of future volume production

Timber markets in the catchment area are limited in comparison to other regions like the US South. The scale of the landscape and the inaccessible nature of many of the forest areas limit the viability of access to multiple markets. Sawmills produce the highest value end-product and these markets have driven the harvesting of forest tracts for many years. Concessions to harvest timber are licensed either by volume or for a specific area from the provincial forest service. This comes with a requirement to ensure that the forest regrows and is appropriately managed after harvesting.

There are no pulp mills within the catchment area and limited alternative markets for the lowest grades of roundwood or sawmill residuals other than the pellet mills; consequently, the pellet mills have a close relationship with the sawmills.

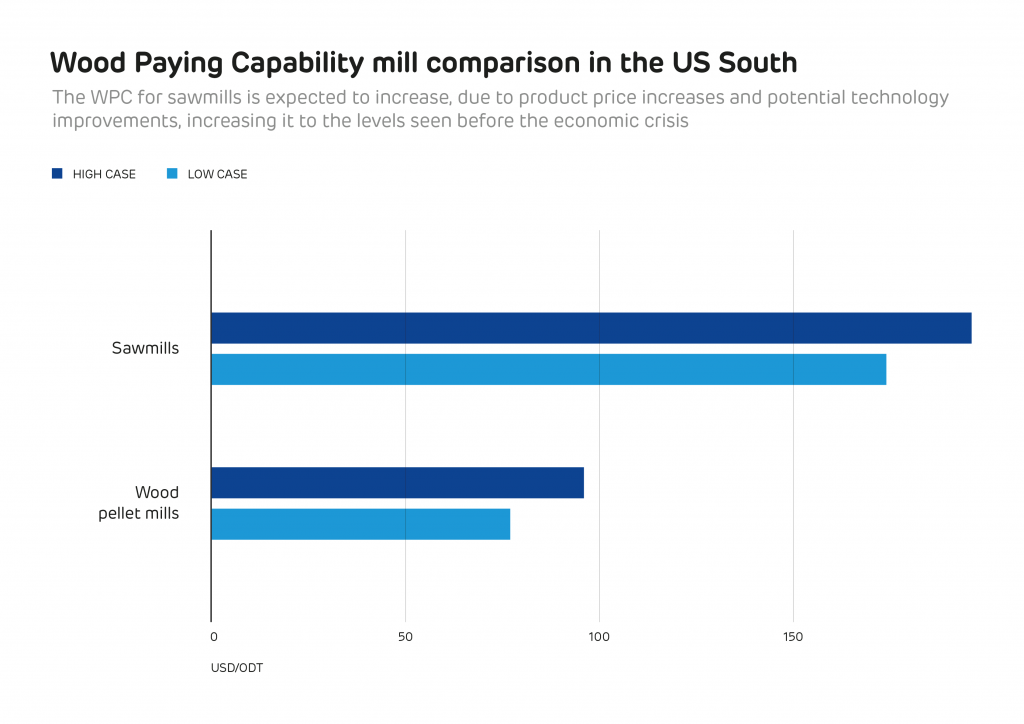

Prices for standing timber on public land are determined by the provincial government using results from public timber sales and set according to the species and quality of timber produced (from the highest-grade logs through to forest residuals). The lack of market diversity and challenging logistics mean that there is little competition for mill residuals and low-grade fibre. The price differential in end-product value between sawtimber and wood pellets ensures that fibre suitable for sawmill utilisation does not get processed by the pellet mill. A very small volume of larger dimension material can end up in a low value market when there are quality issues that limit the value for sawtimber (e.g. rotten core, structural defects) but this represents a very small proportion of the supply volume. There is no evidence that pellet mills have displaced other markets within this catchment area.

In ecological terms, biomass refers to any type of organic matter. When it comes to energy, biomass is any organic matter that can be used to generate energy, for example wood, forest residues or plant materials.

Biomass used and combusted for energy can come in a number of different forms, ranging from compressed wood pellets – which are used in power stations that have upgraded from coal – to biogas and biofuels, a liquid fuel that can be used to replace fossil fuels in transport.

The term biomass also refers to any type of organic material used for energy in domestic settings, for example wood burned in wood stoves and wood pellets used in domestic biomass boilers.

Biomass is organic matter like wood, forest residues or plant material, that is used to generate energy.

Biomass can be produced from different sources including agricultural or forestry residues, dedicated energy crops or waste products such as uneaten food.

Drax Power Station uses compressed wood pellets sourced from sustainably managed working forests in the US, Canada, Europe and Brazil, and are largely made up of low-grade wood produced as a byproduct of the production and processing of higher value wood products, like lumber and furniture.

Biomass producers and users must meet a range of stringent measures for their biomass to be certified as sustainable and responsibly sourced.

Biomass grown through sustainable means is classified as a renewable source of energy because of the process of its growth. As biomass comes from organic, living matter, it grows naturally, absorbing carbon dioxide (CO2) from the atmosphere in the process.

It means when biomass is combusted as a source of energy – for example for heat or electricity production – the CO2 released is offset by the amount of CO2 it absorbed from the atmosphere while it was growing.

Biomass is a renewable, sustainable form of energy used around the world.

Biomass has been used as a source of energy for as long as humans have been creating fire. Early humans using wood, plants or animal dung to make fire were all creating biomass energy.

Today biomass in the form of wood and wood products remains a widely used energy source for many countries around the world – both for domestic consumption and at grid scale through power stations, where it’s often used to replace fossil fuels with much higher lifecycle carbon emissions.

Drax Power Station has been using compressed wood pellets (a form of biomass) since 2003, when it began research and development work co-firing it with coal. It fully converted its first full generating unit to run only on compressed wood pellets in 2013, lowering the carbon footprint of the electricity it produced by more than 80% across the renewable fuel’s lifecycle. Today the power station runs mostly on sustainable biomass.

View here

Electricity systems around the world are decarbonising and increasingly switching to renewable power sources. While intermittent sources, such as solar and wind, are the fastest growing types of renewables being installed globally, the reliability and flexibility of biomass and its ability to offer grid stabilisation services such as frequency control and inertia make it an increasingly necessary source of renewable power. According to the International Energy Agency biomass generation is forecast to expand as planned projects come online.

Biomass comes in many different forms. When looking to assess future demand and use, it is important to recognise benefits that different types of biomass bring. Compressed wood pellets are just one small part of the biomass spectrum, which includes many forms of agricultural and livestock residues, waste and bi-products – much of which is currently discarded or underutilised.

Maximising the use of these wastes and residues provides plenty of scope for expansion of the biomass energy sector around the world. The global installed capacity for biomass generation is expected to reach close to 140 gigawatts (GW) by 2026, which will be fuelled primarily by expansion in Asia using residues from food production and the forestry processing industry.

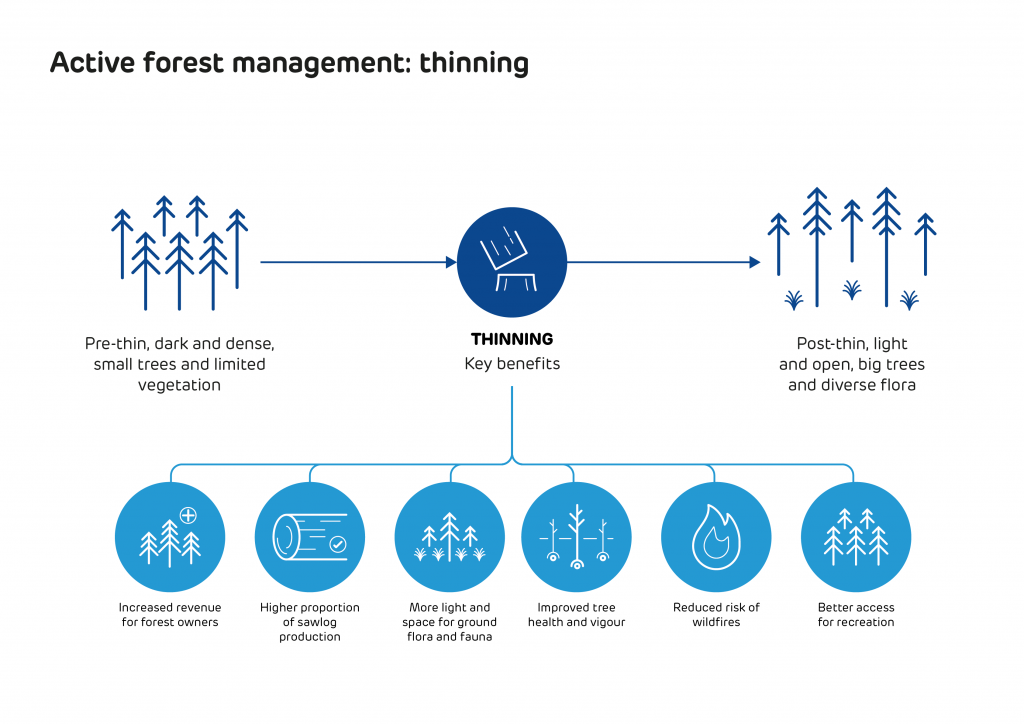

However, the use of woody biomass can also provide many benefits too, such as supplying a market for thinnings, providing a use for harvesting residues, encouraging better forest management practices and generating increased revenue for forest owners.

In areas like the US South, traditional markets for forest products have declined, whilst forest growth has significantly increased. According to the USDA Forest Inventory and Analysis (FIA) data, there is an average annual surplus of growth in the US South of more than 176 million cubic metres compared to removals – that’s enough to make around 84 million tonnes of wood pellets a year, from just one supply region.

Of course, not all of this surplus growth could or should be used for bio-energy, much of it is suitable for high value markets like saw-timber or construction and some of it is located on inaccessible or protected sites. However, new and additional markets are essential to maintain the health of the forest resource and to encourage forest owners to retain and maintain their forest assets.

In the current wood pellet supply regions for Europe, Pöyry management consulting has calculated that there is a surplus of low grade wood fibre and residues that could make an additional 140 million tonnes of wood pellets each year.

Compressed wood pellets on a conveyor belt

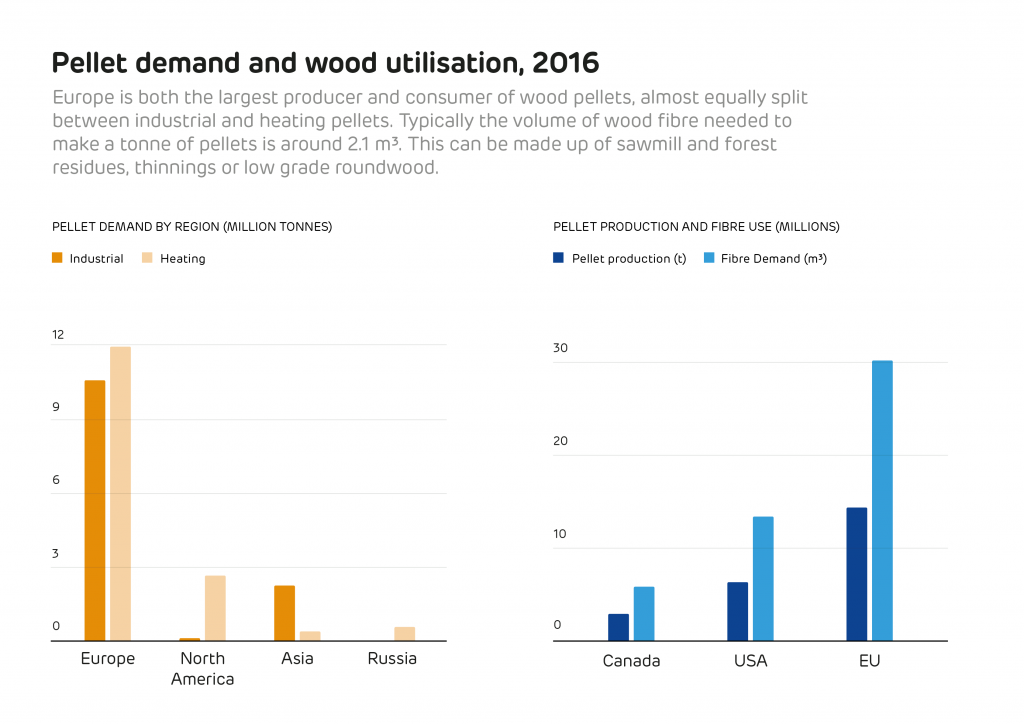

It is also necessary to look at the global production of all wood products to put wood pellet production into context. In 2016 the global production of industrial roundwood (the raw material used for construction, furniture, paper and other wood products) was 1.87 billion cubic metres, while the global production of wood fuel (used for domestic heating and cooking) was 1.86 billion cubic metres[1]. Only around 1.6% of this feedstock was used to make wood pellets, both for industrial energy and residential heat. The total production of wood pellets in 2016 was 28.4 million tonnes, of which only 45% was used for industrial energy[2].

While Forestry consulting and research firm Forisk predicts demand for industrial wood pellets (those used in electricity generation rather than residential heating) will grow globally at an annual rate of 15% for the next five years, reaching 27.5 megatonnes (Mt) by 2023, they are also clear that this growth, in context, will not impact forest volumes or other markets:

‘The wood pellet industry in the US South is not exploding, it is a tiny component of the overall market. Forest volumes in the South in total will continue to grow for decades no matter what bioenergy markets or housing markets do. The wood pellet sector simply and unequivocally cannot compete economically with US pulp and paper mills (80% of pulpwood demand in South) for raw material on a head-to-head basis[3].’

So, while demand for wood pellets is likely to increase over the next 10 years, this increase will be well within the scope of existing surplus fibre. The question, therefore, is can suppliers keep up with this demand? And can they do this while ensuring it remains sustainable, reliable and renewable?

In the short-term, intelligence firm Hawkins Wright estimates global demand will increase by almost 30% during 2018 to reach 20.4 Mt, while Forisk predicts a smaller jump: an almost 5 Mt increase compared to 2017.

Most of this will continue to come from Europe (73% of global demand by 2021, more than 80% in 2018), where projects such as Lynemouth Power Station’s conversion from coal to biomass, as well as five co-firing units in the Netherlands are all set to come online very soon. While smaller in number, Asia is also developing a growing appetite for biomass and in 2018 demand is forecast to grow by 1.98 Mt.

These estimates might paint a picture of a continually soaring demand, but Forisk’s forecast actually expect this growth to plateau, levelling off around 2023 at 27.5 Mt. Hawkins Wright expects a similar slow down, forecasting manageable growth of under 15% between 2023 and 2026.

A forestry specialist at Drax Group, believes this plateau could come even sooner.

“Current and future forecasts in industrial wood pellet demand are based on a series of planned conversions and projects coming online,” he explains.

“But once these projects are active, demand in Europe will likely plateau around 2021 and then gradually reduce as various EU support schemes for industrial biomass come to an end. Any long term use of biomass is likely to be based on agricultural residues and wastes.”

But even with this expected slowdown, the biomass demand of the near future will be substantially higher than it is right now. So, the question remains, can suppliers meet the need for biomass pellets?

Meeting this growing demand depends on two factors: sufficient raw materials and the production capabilities to turn those materials into biomass pellets.

In today’s market, there’s no shortage of raw materials and low grade fibre. Instead, what could cause challenges is the production of pellets.

Hawkins Wright reports the capacity for global industrial pellet production was roughly 21.4 Mt a year at the end of 2017 and will increase by a further 3 Mt by 2019 as facilities currently under construction reach completion.

It means that to meet even Forisk’s conservative 27.5 Mt prediction by 2023, pellet production needs to increase. However, Drax’s forestry specialist points to the three to four years needed to complete pellet facilities and the relatively short period of time financial support programmes will remain in place as something that could lead to a slowdown in new plants coming online. Instead, he says, expansions of existing plants and the increased use of small-scale facilities will become crucial to increasing overall production.

However the biomass market changes and develops, it remains critical that proper regulation is in place, efficiencies are found and that technological innovation continues within the forestry industry so forests are grown and managed sustainably.

As we move into a low-carbon future we know that biomass demand will increase. But for this to be truly beneficial and sustainable we need to ensure we are not only meeting the demand of today but also of tomorrow, the day after tomorrow and beyond.

[1] Source: FAOSTAT

[2] Source: Hawkins Wright, The Outlook for Wood Pellets, Q4 2017

[3] https://www.forisk.com/blog/2015/10/23/nibbling-on-a-chicken-or-nibbling-on-an-elephant-another-example-of-incomplete-and-misleading-analysis-of-us-forest-sustainability-and-wood-bioenergy-markets/

In 2013, Drax co-founded the SBP together with six other energy companies.

SBP builds upon existing forest certification programmes, such as the Sustainable Forest Initiative (SFI), Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) and the Programme for the Endorsement of Forest Certification (PEFC). These evidence sustainable forest management practices but do not yet encompass regulatory requirements for reporting greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. This is a critical gap for biomass generators, who are obligated to report GHG emissions to European regulators.

There is also limited uptake of forest-level certification schemes in some key forest source areas. SBP is working to address these challenges.

SBP certification provides assurance that woody biomass is supplied from legal and sustainable sources and that all regulatory requirements for the users of biomass for energy production are met. The tool is a unique certification scheme designed for woody biomass, mostly in the form of wood pellets and wood chips, used in industrial, large-scale energy production.

SBP certification is achieved via a rigorous assessment of wood pellet and wood chip producers and biomass traders, carried out by independent, third party certification bodies and scrutinised by an independent technical committee.

Of the air that makes up our atmosphere, the most abundant elements are nitrogen and oxygen. In isolation, these elements are harmless. But when exposed to extremely high temperatures, such as in a power station boiler or in nature such as in lightning strikes, they cling together to form NOx.

NOx is a collective term for waste nitrogen oxide products – specifically nitric oxide (NO) and nitrogen dioxide (NO2) – and when released into the atmosphere, they can cause problems like smog and acid rain.

At a power station, where fuel is combusted to generate electricity, some NOx is inevitable as air is used in boilers to generate heat. But it is possible to reduce how much is formed and emitted. At Drax Power Station, a system installed by Siemens is doing just that.

It begins with a look into swirling clouds of fire.

“Getting rid of NOx is, at heart, a problem of getting combustion temperatures to a point where they are hot enough to burn fuel effectively. Too hot and the combustion will form excess amounts of NOx gases. Too cool and it won’t combust efficiently,” says Julian Groganz, a Process Control Engineer who helped install the SPPA-P3000 combustion optimisation system at Drax. “Combustion temperatures are the result of the given ratio of fuel and air in each spot of the furnace. This is our starting point for optimisation.”

An industrial boiler works in a very different way to your average fireplace. In Drax’s boilers, the fuel, be it compressed wood pellets or coal, is ground up into a fine powder before it enters the furnace. This powder has the properties of a gas and is combusted in the boilers.

“The space inside the boiler is filled with swirling clouds of burning fuel dust,” says Groganz. Ensuring uniform combustion at appropriate temperatures within this burning chamber – a necessary step for limiting NOx emissions – becomes rather difficult.

If you’re looking to balance the heat inside a boiler you need to understand where to intervene.

The SPPA-P3000 system does this by beaming an array of lasers across the inside of the boiler. “Lasers are used because different gases absorb light at different wavelengths,” explains Groganz. By collecting and analysing the data from either end of the lasers – specifically, which wavelengths have been absorbed during each beam’s journey across the boiler – it’s possible to identify areas within it burning fuel at different rates and potentially producing NOx emissions.

For example, some areas may be full of lots of unburnt particles, meaning there is a lack of air causing cold spots in the furnace. Other areas may be burning too hot, forcing together nitrogen and oxygen molecules into NOx molecules. The lasers detect these imbalances and give the system a clear understanding of what’s happening inside. But knowing this is only half the battle.

“The next job is optimising the rate of burning within the boiler so fuel can be burnt more efficiently,” explains Groganz. This is achieved by selectively pumping air into the combustion process to areas where the combustion is too poor, or limiting air in areas which is too rich.

“If you limit the air being fed into air-rich, overheated areas, temperatures come down, which reduces the production of NOx gases,” says Groganz. “If you add air into air-poor, cooler areas, temperatures go up, burning the remaining particles of fuel more efficiently.”

It’s a two-for-one deal: not only does balancing temperatures inside the boiler limit the production of NOx gases, but also improves the overall efficiency of the boiler, bringing costs down across the board. It even helps limit damage to the materials on the inside the boiler itself.

Thanks to this system, and thanks to its increased use of sustainable biomass (which naturally produces less NOx than coal), Drax has cut NOx emissions by 53% since the solution was installed. More than that, it is the first biomass power station to install a system of this sophistication at such scale. This means it is not just a feat of technical and engineering innovation, but one paving the way to a cleaner, more efficient future.