Key takeaways:

- Working forests, where wood products are harvested, are explicitly managed to balance environmental and economic benefits, while encouraging healthy, growing forests that store carbon, provide habitats for wildlife, and space for recreation.

- But there is no single management technique. The most effective methods vary depending on local conditions.

- By employing locally appropriate methods, working forests have grown while supporting essential forestry industries and local economies.

- Forests in the U.S. South, British Columbia, and Estonia all demonstrate how local management can deliver both environmental and economic wins.

Forests are biological, environmental, and economic powerhouses. Collectively they are home to most of the planet’s terrestrial biodiversity. They are responsible for absorbing 7.6 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide (CO2) equivalent per year, or roughly 1.5 times the amount of CO2 produced by the United States on an annual basis. And working forests, which are actively managed to generate revenue from wood products industries, are important drivers for the global economy, employing over 13 million people worldwide and generating $600 billion annually.

But as important as forests are globally, the key to maximizing working forests’ potential lies in smart, active forest management. While 420 million hectares of forest have been lost since 1990 through conversion to other land uses such as for agriculture, many working forests are actually growing both larger and healthier due to science-based management practices.

The best practices in working forests balance economic, social, and environmental benefits. But just as importantly, they are tailored to local conditions and framed by appropriate regional regulations, guidance, and best-practice.

The following describes how three different regions, from which Drax sources its biomass, manage their forests for a sustainable future.

British Columbia: Managing locally for global climate change

British Columbia is blanketed by almost 60 million hectares of forest – an area larger than France and Germany combined. Over 90% of the forest land is owned by Canada’s government, meaning the province’s forests are managed for the benefit of the Canadian people and in collaboration with First Nations.

From the province’s expanse of forested land, less than half a percent (0.36%) is harvested each year, according to government figures. This ensures stable, sustainable forests. However, there’s a need to manage against natural factors.

In 2017, 2018, and 2020 catastrophic fires ripped through some of British Columbia’s most iconic forest areas, underscoring the threat climate change poses to the area’s natural resources. One response was to increase the removal of stands of trees in the forest, harvesting the large number of dead or dying trees created by pests that have grown more common in a warming climate.

By removing dead trees, diseased trees, and even some healthy trees, forest managers can reduce the amount of potential fuel in the forest, making devastating wildfires less likely. There are also commercial advantages to this strategy. Most of the trees removed are low quality and not suitable for processing into lumber. These trees can, however, still be used commercially to produce biomass wood pellets that offer a renewable alternative to fossil fuels. This means local communities don’t just get safer forests, they get safer forests that support the local economy.

The United States: Thinning for healthier forests

The U.S. South’s forests have expanded rapidly in recent decades, largely due to growth in working forests on private land. Annual forest growth in the region more than doubled from 193 million cubic metres of wood in 1953 to 408 million cubic meters by 2015.

This expansion has occurred thanks to active forest product markets which incentivise forest management investment. In the southern U.S. thinning is critical to managing healthy and productive pine forests.

Thinning is an intermediate harvest aimed at reducing tree density to allocate more resources, like nutrients, sunlight, and water, to trees which will eventually become valuable sawtimber. Thinning not only increases future sawtimber yields, but also improves the forest’s resilience to pest, disease, and wildfire, as well as enhancing understory diversity and wildlife habitat.

While trees removed during thinning are generally undersized or unsuitable for lumber, they’re ideal for producing biomass wood pellets. In this way, the biomass market creates an incentive for managers to engage in practices that increase the health and vigour of forests on their land.

The results speak for themselves: across U.S. forestland the volume of annual net timber growth 36% higher than the volume of annual timber removals.

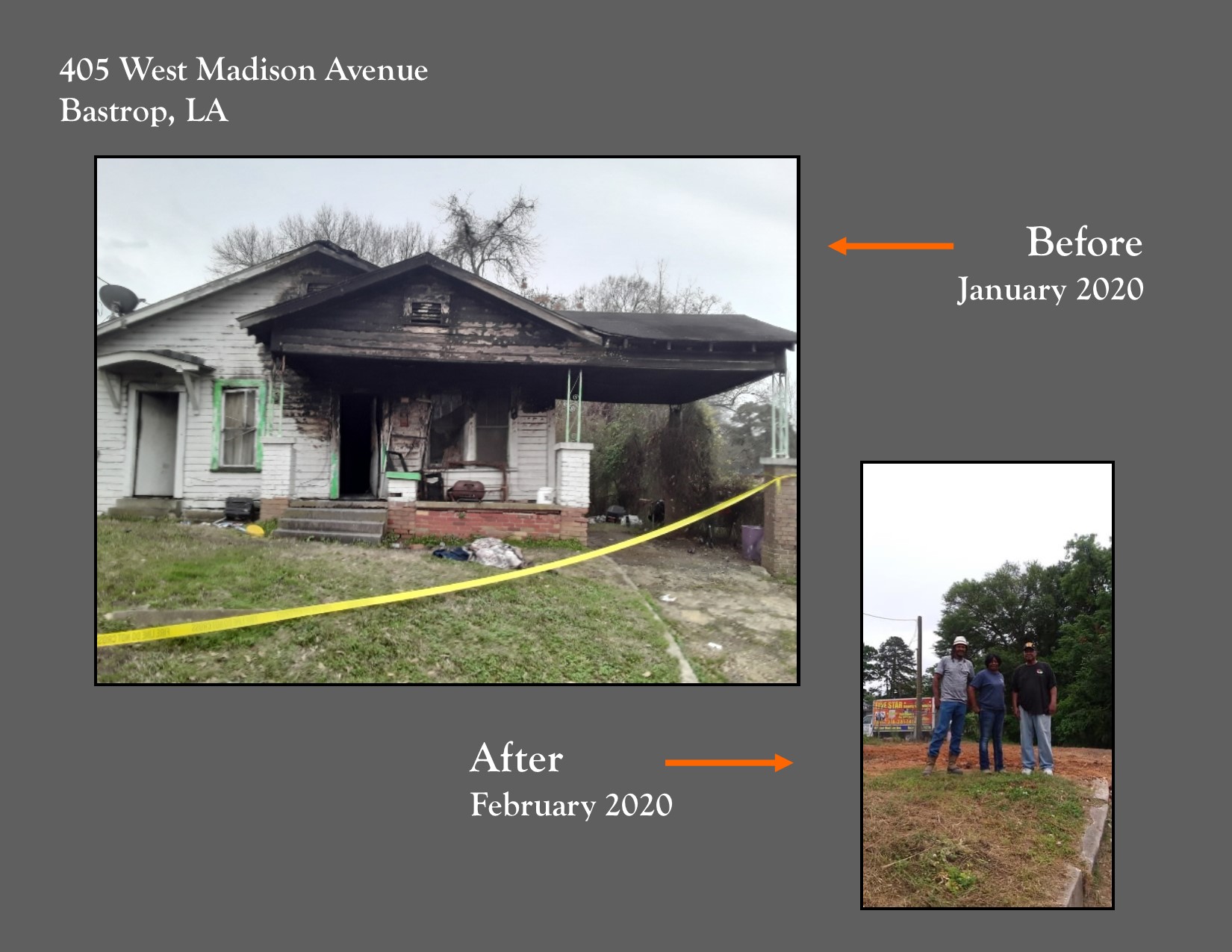

A managed working forest in the US South

Estonia: Seeding the future

Though Estonia is not a large country, approximately half of it is covered in trees, meaning forestry is integral to the country’s way of life. Historically, harvesting trees has been an important part of the national economy, and the government has established strict laws to ensure sustainable management practices.

These regulations have helped Estonia increase its overall forest cover from about 34% 80 years ago to over 50% today. And, as in the U.S. South, the volume of wood harvested from Estonia’s forests each year is less than the volume added by tree growth.

Sunrise and fog over forest landscape in Estonia

Estonia has managed to increase its growing forest stock by letting the average age of its forests increase. This is partially due to Estonia having young, fast-growing forests in areas where tree growth is relatively new. But it is also due to regulations that require harvesters to leave seed trees.

Seed trees are healthy, mature trees, the seeds from which become the forest’s next generation. By enforcing laws that ensure seed trees are not harvested, Estonia is encouraging natural regeneration of forests. As in the U.S. South protecting these seed trees from competition for water and nutrients means removing smaller trees in the area. While these smaller trees may not all be suitable for lumber, they are a suitable feedstock for biomass. It means managing for natural regeneration can still have economic, as well as environmental, advantages.

Different methods, similar results

Laws, landownership, and forestry practices differ greatly between the U.S. South, British Columbia, and Estonia, but all three are excellent examples of how local forest management contributes to healthy rural economies and sustained forest coverage.

While there are many different strategies for creating a balance between economic and environmental interests, all successful strategies have something in common: They encourage healthy, growing forests.