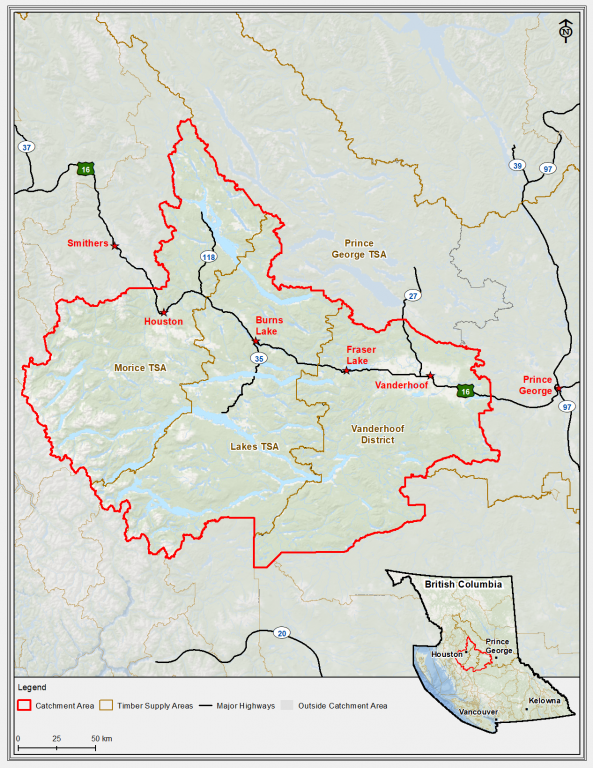

The eigth report in a series of catchment area analyses for Drax looks at the fibre sourcing area surrounding two compressed wood pellet plants operated by Pinnacle.

This part of interior British Columbia (BC) is unique in the Drax supply chain. Forest type, character, history, utilisation, natural challenges, logistics, forest management and planning are all very different to the other regions from which Drax sources biomass. Recently devasted by insect pest and fire damage, Arborvitae Environmental Services has produced a fascinating overview of the key issues and challenges that are being experienced in this region.

A positive response to natural disasters

Like the entire BC Interior, the area has suffered a devastating attack of Mountain Pine Beetle (MPB) damage over the last 20 years which has completely dominated every forest management decision and action. Within the catchment area, the MPB killed an estimated 157 million cubic metres (m3) between 1999 and 2014, representing 42% of the estimated 377 million m3 of total standing timber in the catchment area in 1999. In addition, severe wildfires in 2018 burned an estimated 7.1 million m3.

These natural events have had a devastating impact on the forest resource. Harvesting increased significantly to utilise the dead and dying timber as lumber in sawmills whilst it was still viable.

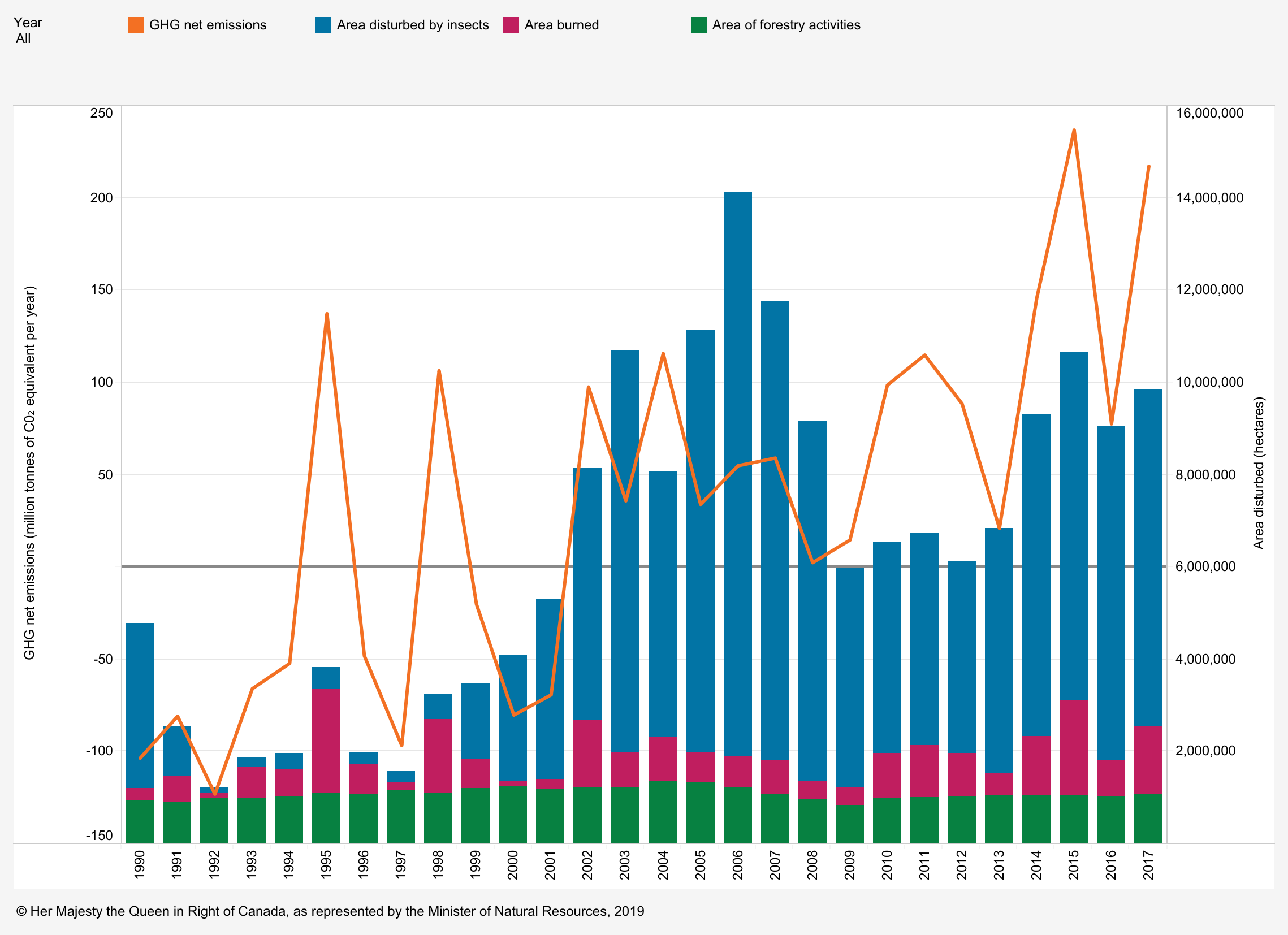

Net carbon emissions in Canada’s managed forest: All areas, 1990–2017; illustrates that the impact of fires and insect damage have been far more significant, by hectares affected, than forestry activity; Chart via Natural Government of Canada

The Pinnacle pellet mills at Burns Lake and Houston were established alongside the sawmills to utilise the sawmill residues as there were no other viable markets for this material. These sawmills draw fibre from a large distance, up to 300 miles away. Therefore, the size of the catchment area in this piece of analysis is determined by the sourcing practices of the sawmills rather than the economic viability of low grade roundwood transport to the pellet mill (see Figure 1).

Damage to pine trees by Mountain Pine Beetle (MPB)

Utilising forest residues

The two mills producing high-density biomass pellets have provided an essential outlet for residue material that would otherwise have no other market and until very recently were supplied almost entirely by mill residuals. As the quantity of dead and dying timber has reduced and sawmill production has declined, the pellet mills are beginning to utilise more low-grade roundwood and forest residues (that are otherwise heaped and burned at roadside following harvest) to supplement the sawmill co-products.

Primarily State owned managed forests

The total land area in the catchment for Burns Lake and Houston is 4.47 million hectares (ha) of which 3.75 million ha is classed as forest land, 94% of the catchment area is public land under provincial jurisdiction. The provincial forest service is responsible for all decisions on land use and forest management on public land, in consultation with communities and indigenous groups, determining which areas are suitable for timber production and which areas require protection. Approximately 34% of the catchment area is not available for commercial timber harvesting because it is either non-forested or it has low productivity, and other operational challenges, or it is protected for ecological and wildlife reasons.

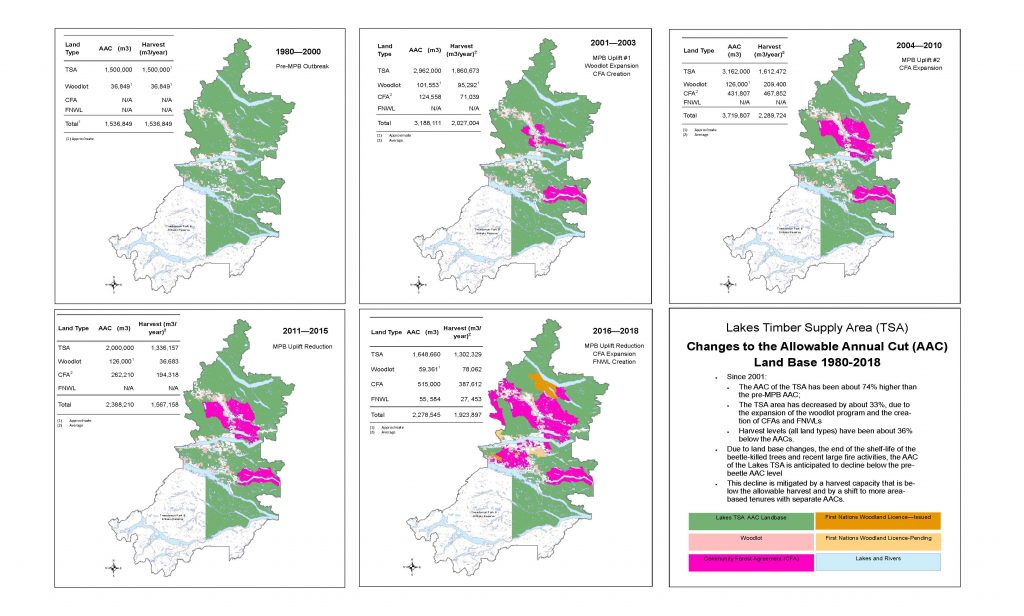

The Chief Forester for the province sets the Annual Allowable Cut (AAC) which determines the quantity of timber that can be harvested each year. Ordinarily this will be based on the sustainable yield capacity of the working forest area, but in recent years the MPB damage has necessitated a significant increase in AAC to facilitate the salvage of areas that have been attacked and damaged (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Changes in Annual Allowable Cut 1980 to 2018 (Source: Nadina District FLNRORD) [Click to view/download]

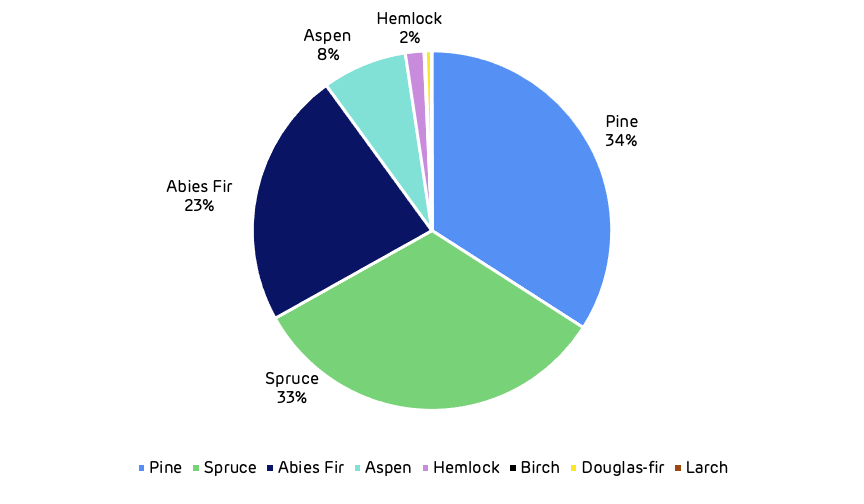

The forest area is dominated by coniferous species (see Figure 3) predominantly lodgepole pine, spruce and fir (90% of the total area), with hardwood species (primarily aspen) making up just 8% of the total area.

Figure 3: Species composition of forest land in the catchment area.

Managing beetle damaged areas

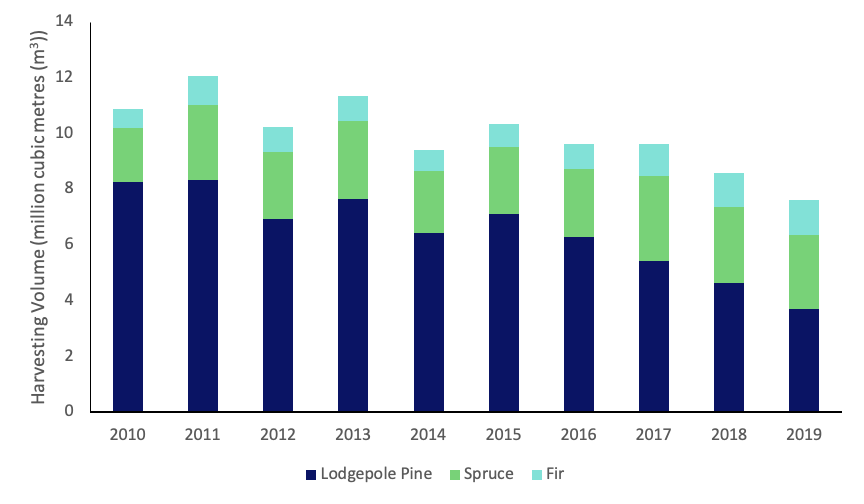

The annual harvest volume was at a peak in the early part of the last decade at over 12 million m3 in 2011. This has now declined by around 4.5 million m3 in 2019 (see Figure 4) as the beetle damaged areas are cleared and replanted. The AAC and harvesting levels are expected to be reduced in the future to allow the forest to regrow and recover.

Figure 4: Annual change in harvest volume of major species

Future increases in forest growth rates

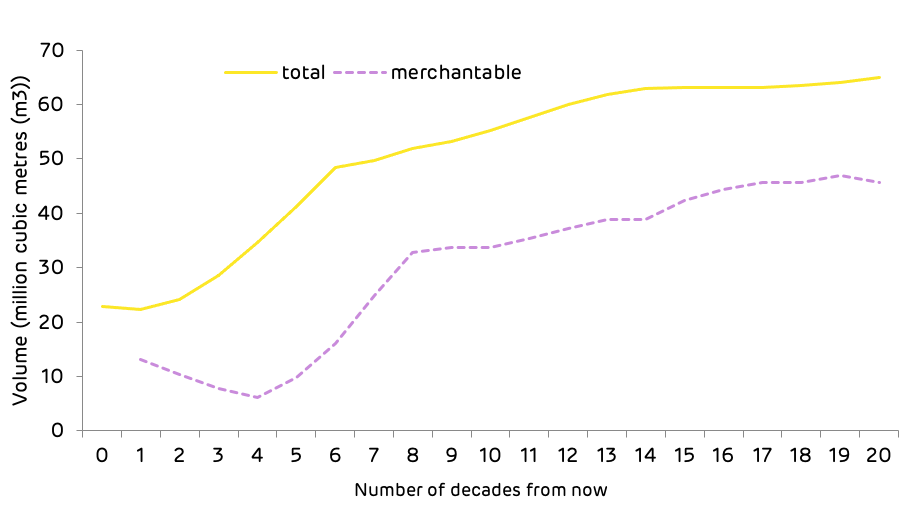

Historically, the forest area has naturally regenerated with self-seeded stands reaching a climax of mature pine, spruce, and Abies fir mixtures. As the forest matured, it would often be subject to natural fires or other disturbance which would cause the cycle to begin again. Following the increase in harvesting of beetle damaged areas, many forests are now replanted with mixtures of spruce and pine rather than naturally regenerated. This is likely to lead to an increase in forest growth rates in the future and a higher volume of timber availability once the areas reach maturity (see Figure 5).

Figure 5: Forecast of future volume production

Timber markets in the catchment area are limited in comparison to other regions like the US South. The scale of the landscape and the inaccessible nature of many of the forest areas limit the viability of access to multiple markets. Sawmills produce the highest value end-product and these markets have driven the harvesting of forest tracts for many years. Concessions to harvest timber are licensed either by volume or for a specific area from the provincial forest service. This comes with a requirement to ensure that the forest regrows and is appropriately managed after harvesting.

There are no pulp mills within the catchment area and limited alternative markets for the lowest grades of roundwood or sawmill residuals other than the pellet mills; consequently, the pellet mills have a close relationship with the sawmills.

Wood price trends

Prices for standing timber on public land are determined by the provincial government using results from public timber sales and set according to the species and quality of timber produced (from the highest-grade logs through to forest residuals). The lack of market diversity and challenging logistics mean that there is little competition for mill residuals and low-grade fibre. The price differential in end-product value between sawtimber and wood pellets ensures that fibre suitable for sawmill utilisation does not get processed by the pellet mill. A very small volume of larger dimension material can end up in a low value market when there are quality issues that limit the value for sawtimber (e.g. rotten core, structural defects) but this represents a very small proportion of the supply volume. There is no evidence that pellet mills have displaced other markets within this catchment area.