Key takeaways:

- British Columbia’s working forests are owned by the province and managed to preserve the environment while supporting forestry industries and local communities.

- When forests are harvested, professional, licensed scalers who are independent of logging companies or sawmills, evaluate the size and quality of wood.

- The processes and assessments made by scalers are extensive and designed to ensure high quality lumber makes its way to commercial markets.

- The careful process of grading wood ensures that only low-quality wood, unusable by lumber sectors is used to produce sustainable biomass pellets.

Healthy working forests are full of different species of trees that serve as essential commercial resource to rural communities. Within these forests are different qualities of wood and trees.

The lumber industry, which drives the commercial forestry in British Columbia, only uses high-quality sawlogs that can be processed into lumber and other valuable solid wood products. When forest companies and the provincial government identify areas of forest suitable for management, the materials are professionally, independently sorted, and selected by the logging operator according to specifications set by the sawmill and by merchantability specifications set by government.

This leaves a range of rejected roundwood trees and other materials that are unsuitable for lumber. Characteristics of rejected material can include undersized logs, rotting in parts, excessive twisting, cracks, large knots, or exposure to damage like fires. But that’s not to say the wood isn’t valuable.

The biomass industry emerged as a way to utilise wood and residues from forestry and sawmill processes. To sort through wood harvests and identify what wood is suitable for lumber, forest companies in British Columbia use a grading system.

The province’s Forest Act outlines that timber harvested from publicly owned Crown must be scaled (measured) and graded. This standardised system means all types of wood are utilised, and the full value of a harvest maximised for lumber and other wood products – ensuring forests remain valuable resources that are replanted and managed for future generations.

Making the grade

The policy of scaling and grading timber has been in action along British Columbia’s coastal forests since as long ago as 1902. And while log grades have evolved and expanded with changes in wood utilisation and forest practices, today’s grading rules and conventions are very similar to those used more than a century ago.

Timber scaling and grading can only be carried out by trained, licenced professionals, known as scalers. The processes and assessments they are required to carry out are rigorous and extensive, as outlined in a regularly updated Scaling Manual.

Scalers apply grading rules to determine: the log’s gross dimensions, estimate what portion of the log is available to produce a given product, and consider the quality of the product that could be produced from the log.

It’s the scaler’s job to assess the visible characteristics of each log and determine what can be recovered from the log given its size and quality characteristics. Results in British Columbia are reported in cubic metres, with one cubic metre of timber viewed as a cubic metre of solid wood (known as firmwood), free of any rot, hole, char, or missing wood. It’s then up to the manufacturer to get the best and most valuable product out of the available volume.

Grade rules typically include three components: minimum or maximum dimensions, a requirement that a percentage of the log’s volume must be available to manufacture a given product, a requirement that a percentage of the product manufactured from the log must meet or exceed a given quality.

By developing methods of taking measurements in British Columbia’s coastal and interior regions, meaningful data is generated to understand the health and quality of the province’s diverse forests.

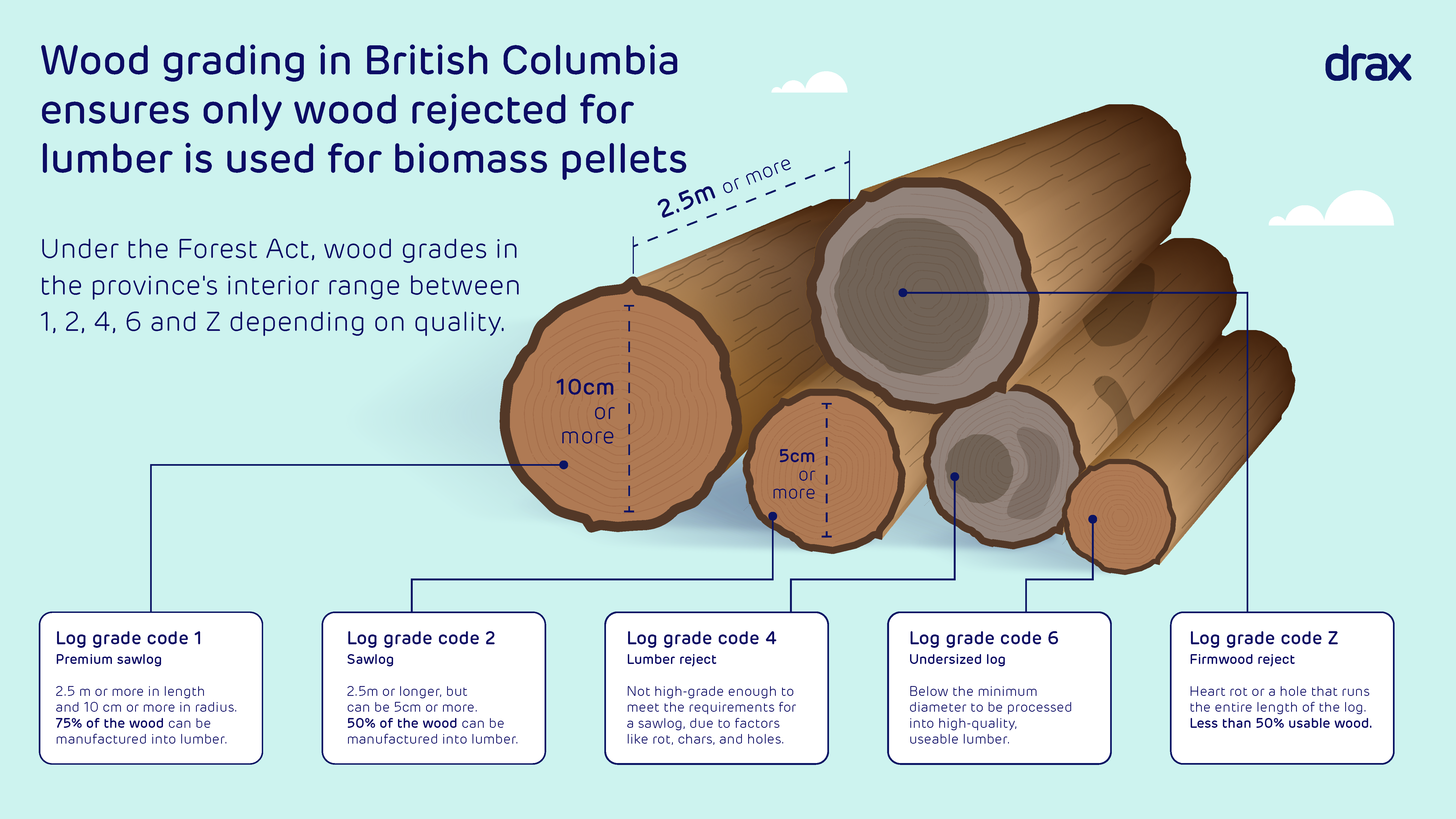

Grade code 1 – Premium sawlogs

The highest-quality and most valuable grade, a grade code 1 log must be 2.5 m or more in length and 10 cm or more in radius. It can also be a slab of wood 2.5 m long and 20 cm wide and 20 cm or more in thickness measured at a right angle to the growth rings.

For species like hemlock, cedar or balsam log or slab, at least 90% of the overall log can be manufactured into lumber, meaning it’s free of rot, chars, or holes, without too many knots or twists.

For other species, at least 75% can be manufactured into lumber. For all species, at least 75% of the lumber will be suitable for sale.

Grade code 2 – Sawlog

Smaller than premium sawlogs, grade code 2 logs are also 2.5 m or longer but can be only 5 cm wide. Grade code 2 sawlogs can also be made from slabs of wood 2.5 m or more in length and 15 cm wide, with a 15 cm or more thickness measured at a right angle to the growth rings.

In species like hemlock or cedar at least 75% of the wood can be manufactured into lumber, while for a balsam logs, it’s at least 67%. For all other species, at least 50% of overall wood can be manufactured into lumber.

Grade code 4 – Lumber reject

Lumber reject is the grade given to a log or slab that’s higher in grade than firmwood reject, but not high-grade enough to meet the requirements for a sawlog, due to factors like rot, chars, and holes.

The reason there is no grade code 3 or 5 is because they were merged into the lumber reject category as the needs of forestry industries changed.

Grade code 6 – Undersized log

An undersized log is the higher in grade than firmwood reject but cut from a tree which was below the minimum diameter to be processed into high-quality, useable lumber.

Grade code Z – Firmwood reject

The lowest grade of wood, a Grade code Z log is not of a high enough quality to be made into lumber.

A log falls into the firmwood reject category if there is heart rot or a hole that runs the entire length of the log, and any firmwood around the defect makes up less than 50% of the overall log.

A scaler may also grade a log as Z if rot is in the log and they estimate the net length of the log to be less than 1.2 m. Sap rot or charred wood within a log where the residual firmwood is less than 10 cm in diameter at the butt end of the log also makes it Grade code Z.

Portions of healthier logs that are less than 10 cm in diameter or portion of a slab that is less than 10 cm in thickness, are also in this category.

Supporting healthy, resilient forests

Wood that is unsuitable for valuable sawlogs was once seen as a residual of forestry harvest and burned as a means of disposal, emitting CO2, and polluting local air. The biomass market, however, processes low-grade wood into a feedstock for renewable electricity, unlocking the full value of forest resources, as well as enhancing ecosystems.

Slash pile in British Columbia

Newly developed forest management practises aimed at mitigating against wildfires, enhancing areas of habitats for wildlife, or restoring fire or diseased-damaged ecosystems, typically generate high volumes of low-grade wood. Without a local biomass market that can purchase and make use of that wood there’s less incentive to carry out these kinds of activities.

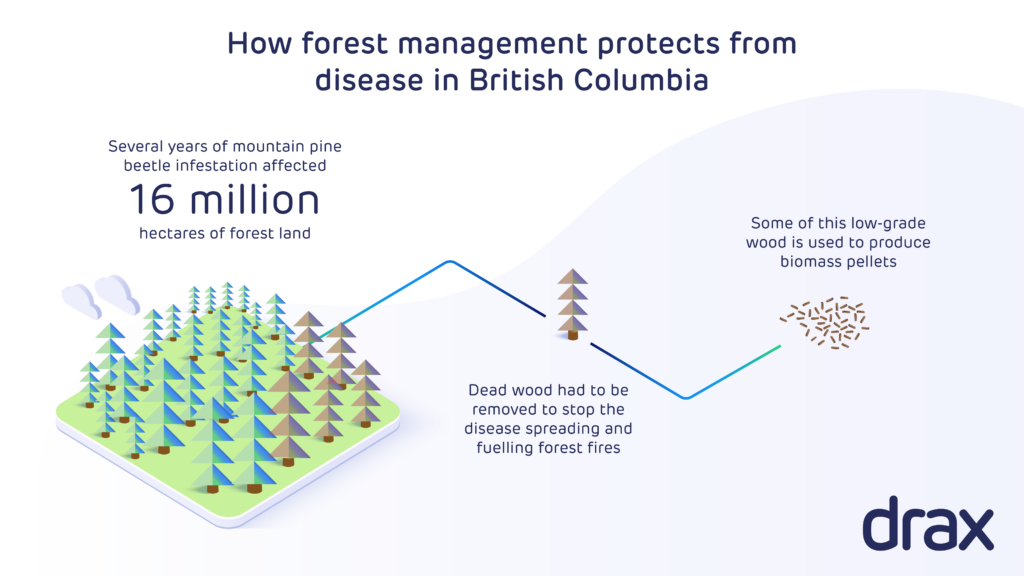

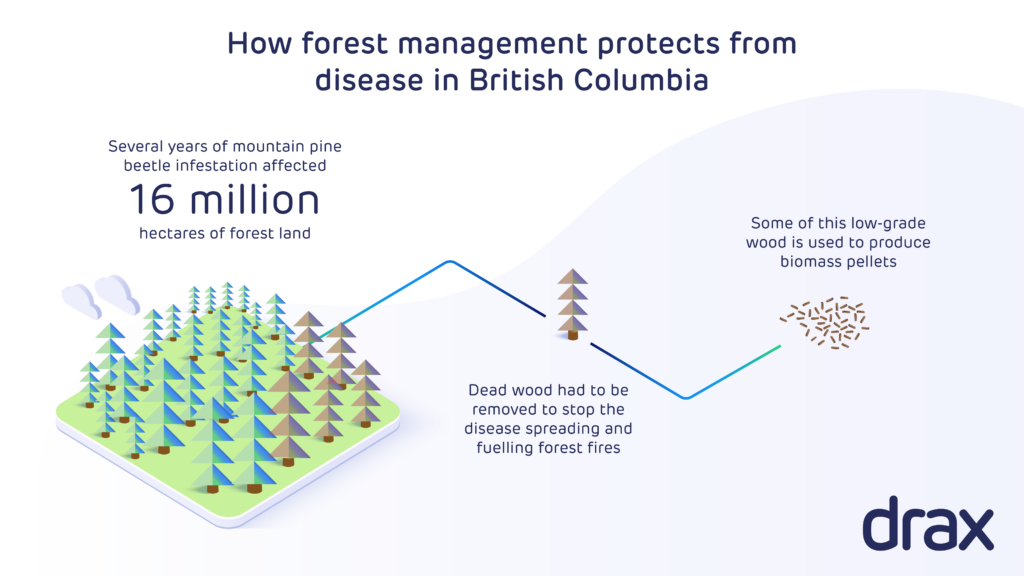

As wildfires and pests, like the mountain pine beetle, become increasing threats for Canadian forests and the rural communities who depend on them for work and leisure, the biomass sector’s participation is key to supporting forest management that ensures healthy, resilient forests.

Click to view/download.

Our community pellet sales days offer half tonne or one tonne totes of pellets at a wholesale rate to our local Princeton community. At our September 15 sales day our plant team sold over 60 units.

Our community pellet sales days offer half tonne or one tonne totes of pellets at a wholesale rate to our local Princeton community. At our September 15 sales day our plant team sold over 60 units.