In brief:

-

Bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS) is increasingly being explored and deployed around the world at heat and power stations, factories and waste-to-energy plants as they aim to achieve net zero through negative emissions.

-

Sweden, Norway, Denmark, the US and UK all have projects either piloting or developing BECCS with the aim of achieving negative emissions to reach their net zero climate goals.

-

Drax, the world’s leading sustainable biomass generation and supply business, has the biggest BECCS project, aiming for eight million tonnes of negative emissions per year by 2030.

-

BECCS projects often form part of low emissions clusters which make use of local sustainable sources of biomass and partner with nearby industries to share CO2 transport and storage infrastructure.

Can a power station make a positive impact on the climate? How about a cement factory? Or even a whole city?

Negative emissions technologies (NETs) aim to help do this by removing carbon dioxide (CO2) from the atmosphere, reducing the detrimental effects of many industrial processes, and even go as far as countering the impacts of climate change.

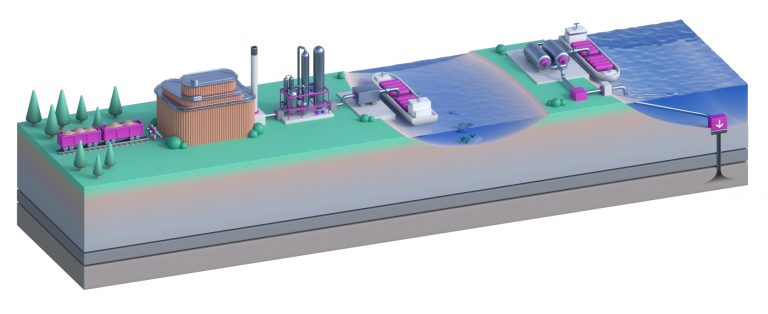

Among NETs, BECCS offers a means of generating electricity or heat while also removing CO2 from the atmosphere. It works by using biomass from sustainable sources, which absorb CO2 from the atmosphere when they grow. When the biomass is used as fuel, that same CO2 is captured and stored, permanently and safely, usually under the seabed.

Trials of BECCS technology are already underway around the world as companies, governments and the third sector work towards their climate goals through negative emissions.

-

Stockholm Exergi – powering the world’s first climate positive city

Stockholm Exergi BECCS pilot plant

Stockholm Exergi is the energy utility responsible for the Swedish capital’s heating, cooling, electricity, and waste processing services. It has bold ambitions to become ‘climate positive’ by 2025. Since December 2019, the company has trialled BECCS at its heat and power cogeneration plant in the Värtan area of Stockholm, where it calculates there is potential to capture 800,000 tonnes of CO2 per year.

The project sources biomass from ‘chopped slash’ made up of branches and treetops, as well as residues from the board, pulp and paper industries, 57% of which come locally from Sweden.

Stockholm’s location is also advantageous for storing CO2, with the nearby North Sea offering multiple sites that meet Stockholm Exergi’s criteria for carbon sequestration.

Stockholm Exergi’s BECCS plant would send captured carbon to the Northern Lights project

Fabian Levihn, head of R&D at Stockholm Exergi highlights the economic advantages BECCS offers as a means of carbon offsetting for industries with hard-to-abate emissions. “For industrial emitters to remove the last 20% needed to reach net zero greenhouse gases it will cost as much as US$800 per tonne of CO2 or equivalent,” explains Levihn.

Fabian Levihn, head of R&D at Stockholm Exergi

“If BECCS can be realised at $100 per tonne of CO2, it offers an upside in terms of economic efficiency for climate change abatement of $700 per tonne.”

Recent modelling by leading energy consultancy Baringa for Drax has shown that deploying BECCS in the 2020s can present billions of pounds of cost savings compared to waiting until later decades, closer to national net zero deadlines.

-

Mendota California – from cantaloupe to carbon capture

The City of Mendota’s seal proudly declares itself ‘The Cantaloupe Center of the world’. Now, however, the agricultural California city is getting a slice of energy innovation with a BECCS project designed to deliver negative emissions and reduce air pollution in the region.

The project comes from a partnership between Schlumberger New Energy, Chevron, Clean Energy Systems and Microsoft. It aims to remove as much as 300,000 tonnes of CO2 annually, the equivalent emissions created generating electricity for more than 65,000 US homes.

The BECCS plant, which is beginning its front-end engineering and design (FEED) phase before a final investment decision in 2022, is optimised for its location. The plant will convert waste from the surrounding agricultural industries, such as almond trees, into a renewable synthesis gas that will be mixed with oxygen in a combustor to generate electricity.

Desert, California

More than 99% of the carbon from this process is expected to be captured and then stored in nearby deep geological formations in the desert landscape. By using an estimated 200,000 tonnes of agricultural waste annually, the plant will also help towards the California Air Resources Control Board’s plan of phasing out almost all agricultural burning in the Valley by 2025.

The project is expected to create up to 300 construction jobs and about 30 permanent jobs once the facility is operating.

-

HeidelbergCement – net zero at an industrial scale

Reaching net zero isn’t just about taking the emissions out of energy generation. Heavy industries must also reduce and remove CO2 with carbon capture and storage (CCS) and BECCS offers a way of achieving this at an even larger scale.

Concrete uses cement

HeidelbergCement Norcem’s plant in Brevik, Norway plans to become the first industrial-scale CCS project at a cement production plant in the world. The project aims to capture 400,000 tonnes of CO2 per year, which will be compressed and transported by ship away from the plant, before being exported via pipeline and stored beneath the North Sea bed.

The plant aims to start CO2 separation from the cement production process by 2024. The end result will be a 50% cut of emissions from the cement produced at the plant. However, CCS is only part of the company’s plan to deliver carbon-neutral cement by 2050.

HeidelbergCement also plans to increase its use of alternative raw materials, primarily waste materials and by-products from other industries – biomass already plays a key part of this, making up 38.1% of the company’s alternative fuel mix. Importantly, it offers a model that can be sustainably applied to cement manufacturing around the world.

-

Ørsted, Aker and Microsoft – Taking the carbon out of Denmark’s heat and power

Not one to be left behind by its Scandinavian neighbours, Denmark has set the ambitious target of reducing its emissions to 70% of 1990 levels by 2030. BECCS and negative emissions will be essential in meeting that goal, and the country already has some of the key infrastructure in place.

Ørsted operates six biomass-fired units that, as well as generating power, provide around one quarter of Denmark’s district heating. This use of combined heat and power stations, mean BECCS can decarbonise both utilities simultaneously. Ørsted, Aker Carbon Capture, and Microsoft are partnering to explore ways to do just that.

Avedøre combined heat and power plant in Denmark operated by Ørsted

Ørsted’s biomass units are powered by low quality or surplus wood that would either be left to rot or be burned in the forest. With the biomass units already in operation, the partnership will address technological, regulatory, and commercial challenges around BECCS. This includes a technology collaboration to integrate Microsoft’s digital expertise into a BECCS project, along with Aker Carbon Capture’s capture technology.

The partnership is exploring the potential to store captured carbon in the North Sea-based Northern Lights project, which is expected to have the capacity to transport, inject, and store up around 1.5 million tonnes of CO2 per year.

Microsoft is already a partner in Northern Lights as part of its efforts to operate as carbon negative by 2030, which has seen it forge partnership across the CCS landscape.

-

Drax – from coal emitter to climate innovator

Drax has evolved from a coal power station to run four of its 600MW-plus generating units on sustainable biomass and is the largest decarbonisation project in Europe.

BECCS pilots at the plant have already been successful in capturing more than a tonne of CO2 a day. By proving the viability of multiple capture technologies, Drax has set 2030 as the date when it aims to become carbon negative, which would also see its BECCS operations scale up to capture as much as 8 million tonnes of CO2 a year.

Drax Power Station with biomass storage domes lit up

The power station is in an advantageous location to deliver such significant negative emissions. Located near the UK’s Humber region, Drax is partnered with a range of industrial emitters through the Zero Carbon Humber partnership, which aims to become the world’s first net zero carbon industrial cluster through a combination of industrial CCS, hydrogen and BECCS.

Sharing carbon capture and transport infrastructure across the region helps to reduce costs for each party, and in Drax’s case can translate into keeping electricity costs down for consumers.

Delivering BECCS, negative emissions and a net zero carbon cluster is an economic driver for the Humber. A recent report found it could create and support almost 48,000 new jobs at the peak of the construction period in 2027 and provide thousands of long term, skilled jobs in the following decades. Negative emissions from BECCS also has an essential role to play in enabling the UK to reach its target of net zero emissions by 2050.

“Drax is ready to invest in this essential technology which will help the UK decarbonise faster and kickstart a whole new industry here,” says Drax CEO Will Gardiner.

“By delivering BECCS, the UK can show the world what can be achieved for the environment and the economy when governments, businesses and communities work together.”

-

Fortum Oslo Varme – turning waste to negative emissions

Agriculture and forestry waste are some of the world’s primary sources of sustainable biomass. However, large amounts of household waste are also biological in origins – for example cardboard or vegetable peels.

Food waste recycling bin in a kitchen

Dealing with cities’ waste is an environmental necessity and key to achieving net zero on a wider scale. Waste-to-energy plants have long provided a means to avoid landfill usage, but by introducing CCS to such facilities they can deliver positive impact to the cities they serve.

The FOV (Fortum Oslo Varme) plant in Oslo delivers heat and power to the Norwegian capital by incinerating waste, approximately 50% of which comes from biological origins. The waste-to-energy facility first launched a CCS pilot in 2016 to remove CO2 from the atmosphere through BECCS.

The project is part of the city’s broader ambition to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions by 95% between 2009 and 2030. As the city’s largest single emissions source, introducing CCS to the FOV can reduce Oslo’s emissions by 14%, an essential step to reach the city’s ambitious climate goals.

The plant currently treats 400,000 tonnes of waste per year that can’t be recycled and has already conducted a 5,500-hour pilot with a 95% capture rate. The issue of non-recyclable waste hangs over almost every city in the world and the FOV’s system could be implemented on as many as 500 similar plants around Europe alone, delivering power, district heating, negative emissions from organic materials and waste reduction.

-

HOFOR – keeping BECCS on budget

HOFOR is a not-for-profit utility currently exploring the potential of BECCS and makes an interesting case study for how the technology can be deployed as economically as possible.

Short for Hovedstadsområdets Forsyningsselskab, which roughly translates as Greater Copenhagen Utility, HOFOR is investigating the addition of BECCS to its combined heat and power (CHP) station. Biomass-fed CHP plants use residual energy from power generation, such as steam, to heat water that is then circulated through a citywide network of pipes to provide heating. It means that the energy utilisation of biomass is very high and, importantly for Nordic countries, provides a large supply of affordable heating.

Maintaining the affordability of its heating supply is crucial for HOFOR, which is bound by regulatory conditions to not undertake investments that make heat more expensive for its customers. For this reason, HOFOR’s exploration of BECCS needs to place an emphasis on technologies that have a high readiness level, and ways to keep costs to a minimum.

By partnering with other local utilities as part of the C4: Carbon Capture Cluster Copenhagen, the company is looking to share the costs of carbon transport and storage infrastructure, keeping heat prices low, while delivering negative emissions.

There is also the potential for HOFOR to sell captured carbon that can be used to create products, such as green aviation fuel. Carbon offsetting offers another way for the utility to invest in BECCS if there is an organised and long-term market for such transactions in place.